Malik Bendjelloul’s stirring documentary Searching for Sugar Man is about mystery and mythmaking and rock-n-roll iconography told through the lens of a dashed career, that of a mellifluous Chicano songwriter and guitarist, primed to explode, who was discarded, dead and prematurely buried—only after which got his chance to become famous.

In telling the story of Sixto Rodriguez, an emerging Detroit music prodigy who by all accounts should have skyrocketed to the rarified realm of Bob Dylan and Lou Reed after the release of his 1970 album, Cold Fact, but instead faded into obscurity for decades, Searching for Sugar Man gives us a contact high by first creating a folkloric legend, and then introducing us to him.

The picture opens in modern South Africa where we meet Stephen “Sugar” Segerman, a rabid and lifelong Rodriguez fan whom we later learn is responsible for the existence of this picture, also nicknamed after one of Rodriguez’ songs about a coke dealer on the skids. Segerman launches a present-day campaign to find the mysterious Rodriguez, whom no one has seen since the early 70s. Why, you may ask? And what is the South Africa-Detroit connection?

Cut to late 60s in Detroit, where one Sixto Rodriguez, who went only by his surname, haunted skid row bars and clubs, a black-clad phantom of the Motor City, quickly building a reputation as a notable musician who just may have been better than Dylan, an assertion we entertain in hearing his songs on the soundtrack. Bendjellou uses crafty animation techniques to bring Detroit of the time alive as a gritty, urbane visual poem, a stark contrast to its sun-bathed South African counterpart.

While Cold Fact was a bust in the United States—suggestions of racism and corrupt record producers enter the discussion—the story goes that a young girl took a bootleg copy of the LP to South Africa on vacation circa 1972, leaving it behind and planting the seeds of a musical revolution, its collection of reedy folk ballads speaking to Afrikaner youth in the midst of an apartheid revolution and hooking into the anti-establishment sentiments conveyed in the collection of tunes. A phenomenon was born.

The album ended up selling millions of copies. Indeed, the film tells us, it was a staple of family record collections in the 70s and 80s, rightfully claiming the spot on the shelf next to Yellow Submarine and very much on that level of cultural importance and impact.

When it was erroneously reported that Rodriguez, the mythical man whom no one had ever seen perform, had actually committed suicide on stage at the height of his career, the legend grew up around him. Cold Fact became a beloved classic; a seminal voice in both the political and cultural lexicon.

But back in Detroit, the very much still-alive Rodriguez, long since finished with music and eking out a hardscrabble life as a day laborer and construction worker, knew nothing of it.

And here is where Searching for Sugar Man expertly depicts a mystery worth of CSI—just where is Rodriguez, what has he been doing, and what happened to all of the profits?

Segerman, working with music journalist Craig Bartholomew-Strydom, take their investigation all the way back to Detroit, where we meet a fabric of former record producers and denizens of Rodriguez’ past and present. Bendjelloul expertly weaves these interviews into near-mythic status, and then he drops the bombshell on us by introducing us to Rodriguez himself, whom we’ve only seen to this point in photographs and heard in recordings.

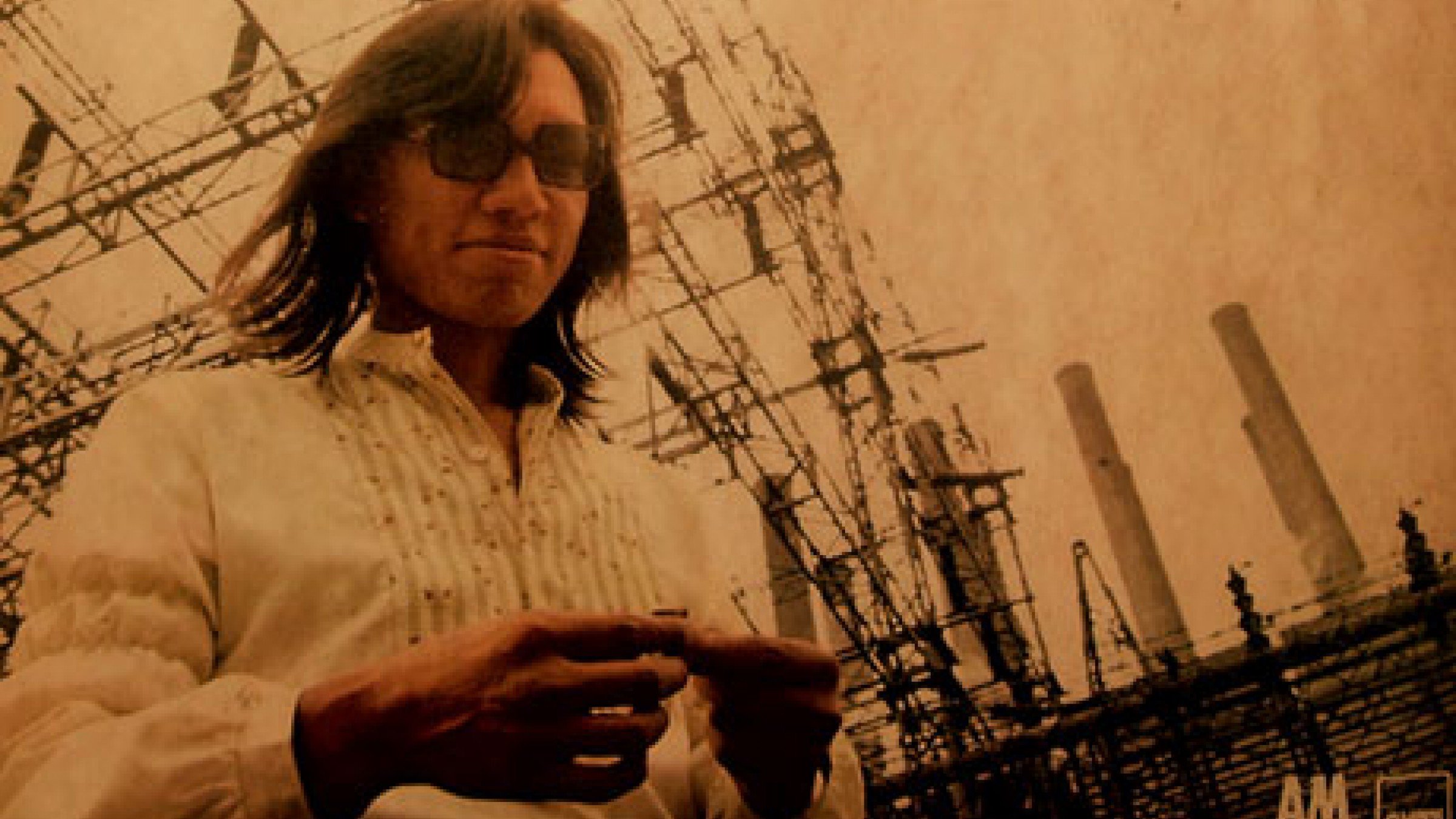

And what a revelation it is. Tall, willowy, hard-lived and gregarious, Rodriguez is first seen opening the window of a modestly spartan home in the middle of a chilly Detroit winter, well past middle-age. The effect is astonishing.

Bendjelloul spends the rest of the film’s running time interviewing Rodriguez and his three daughters, sharing anecdotal stories about the father who made art a driving force in their lives, of course all in disbelief about his superstar status in South Africa.

And then the film charts his first visit to South Africa for a concert, greeted by tens of thousands of adoring fans. The juxtaposition of his hardscrabble existence at home and his Elvis-like reception in South Africa is unfathomable.

And this seems fine with Rodriguez, whom the film suggests never wanted for monetary wealth. Some of the film’s most striking scenes are of Rodriguez today, trudging through icy snow en route to another construction job, making ends meet.

If the film is lacking anything, it’s substance and account of the years that Rodriguez spent out of the spotlight—these blanks are never fully filled in, perhaps an elliptical choice that allows the man to remain cloaked in his aura. We surmise that he had a few marriages, as we know his daughters have different mothers, and that he worked, and hard, for a living. But his darkest moments aren’t here.

No matter. That Rodriguez gets a second chance at music and life feels, in the film, like wish fulfillment, except that it’s all true.

3 1/2 stars.