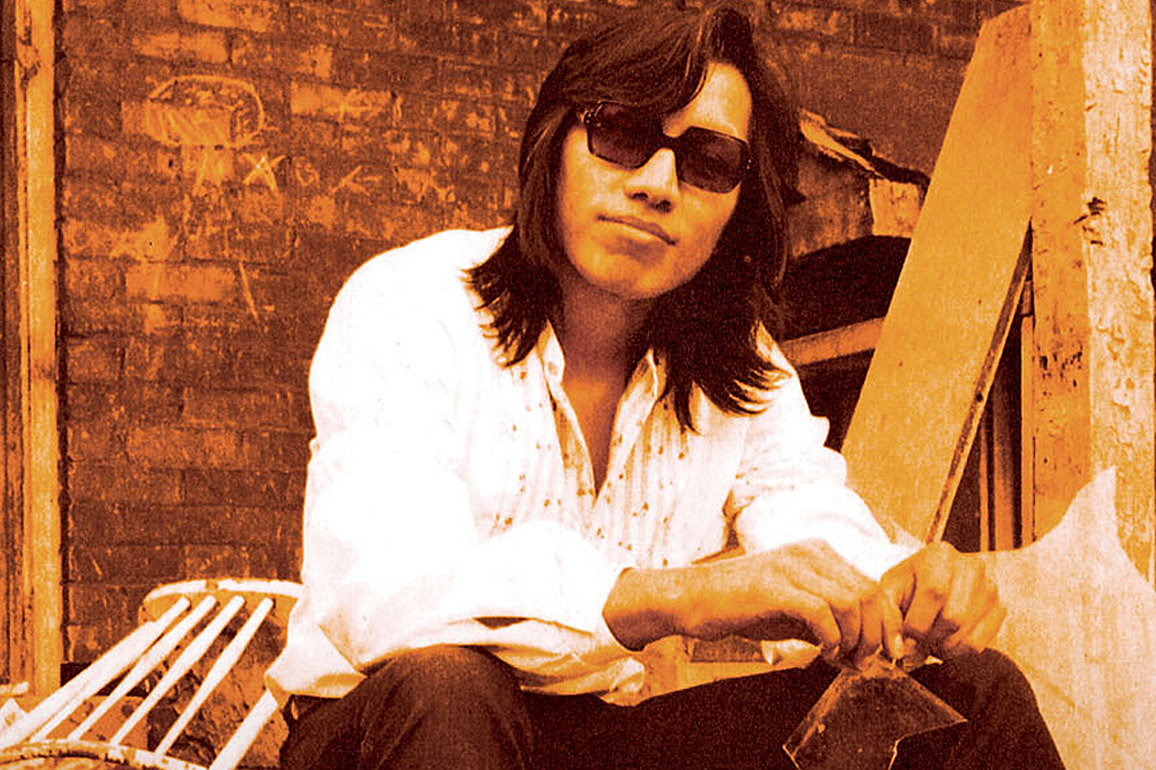

Malik Bendjelloul’s documentary Searching for Sugar Man, which made a splash at Sundance earlier this year, charts the too-strange-to-be-fiction story of Rodriguez, a wunderkind Detroit folk guitarist who by all rights should have become a superstar with the release of his album, Cold Fact, in 1970. Instead, he mysteriously fell into obscurity. It’s a poetic mystery of sorts, an immensely gratifying happy ending story that introduces us to a man who became a cultural icon in his own time, albeit in an apartheid-torn South Africa—but didn’t know a word of it until decades later.

I sat down with Malik Bendjelloul and Rodriguez himself recently—what a thrill—to hear more about this fascinating life story, and found the unlikely icon to be, today, just as political (or musical politico as refers to himself) as his now-classic album would suggest, and as enigmatic as the stunning documentary portrays him.

Rodriguez, take me back to when you first knew you wanted to be a musician.

Rodriguez: I started playing when sixteen, and it was just a family guitar that I picked up because it was in the house. I heard my dad and brothers strumming it too. It kept me out of trouble, or got me into a lot of trouble. But that’s what I chose to do. So for the young ones today, I think if you invest in something early then later on it pays for itself.

Do you pay attention to music today?

Rodriguez: Oh, very much. Well today’s music is a lot of vocal and instrument distortion. I didn’t think drum machines were going to work, but there it is. I like Paolo Nutini. He’s a youngblood on Atlantic Records. He’s got the good looks and the talent and also great pipes and vocals. He can sing well. At Sundance, at the BMI showcase, I got a chance to see James McCartney play, son of Paul, and it’s very, very good stuff. And I met Donovan, who is more Donovan now than he was then! He’s always been at the forefront.

Malik, I know you traveled 16 countries looking for a topic for a film, but this one grabbed you. What was it about the Rodriguez story that resonated?

Malik Bendjelloul: Because I had never read anything like this before. This was on a completely different level. It was like the best story I had ever heard! It was like a fairy tale, and it was true! There was so much. I fell in love so much, and I stayed for years to make it. To make a film as good as the story was the challenge. I thought maybe I wasn’t the one. Maybe it should be someone else more experienced than me to make this film.

The film is really about mythmaking, and you work hard to create, through animation and other means, that aura around Rodriguez’ story. Can you talk about those technical elements? For example, the poetic look of Detroit as well as the look you employed for South Africa?

Bendjellou: When you get into the story and music, it gets inside of you and then when you have the camera, you translate those feelings. You can’t really do anything else but that. You paint the picture of the emotions you get from the story and the music. So it came really naturally, in a way. It was like using the night and winter in Detroit and the summer in South Africa. I could not find two more contrasting places. Those things—summer, winter, seasons—are very poetic, as well as the way cities look. That became the visual poetry, which played with the musical poetry.

And you used the animation for some of the things that you didn’t have footage for.

Bendjelloul: Exactly. I thought it would be more, but funding came late. So I did things with chalk and pen, and simplified everything. Just like the music. It was a hundred and fifty dollar software that I used for the score. They said I shouldn’t use it. Everything was primitive. Simple things often work.

Rodriguez, During all of those years in Detroit, did you ever think you’d be back onstage? That any of this could possibly ever happen?

Rodriguez: Oh, no, never! I was skeptical when Sugar (Stephen Segerman) came to Detroit in 1996 and showed me the CDs, and I got to go there in 1998. And when the audience was singing my songs, I realized that the whole thing was genuine. It was quite indescribable almost. Just great. The band was great. The audiences rushed the stage and showed a lot of emotions. I’m now working bigger venues became of this film. It has really sweetened it.

But for all of those years that you weren’t playing music, as a highly artistic person, you couldn’t have been done with it. Do you think in music, regardless of what you are doing in life?

Rodriguez: Oh, I think in music. I do. It’s like you play guitar and you write lyrics that you might get back to or touch on later. I’m distracted by the social realism of the world. The issue of things in apartheid and what was happening in the U.S. at Kent State, youngbloods were going to Canada and burning their draft cards. And things today, issues like Syria or Darfur. How can you ignore that once it hits your consciousness? So the songs that were the ‘protest songs’ of the 70s and late 60s were I Am a Rock, Eve of Destruction and Dylan’s poetry—they all helped us get through that time period. So too in South Africa, the youth asked questions about the situation, and a lot of the audience in South Africa and musicians and soldiers, they defended their country; there was conscription there as well in Angola and Namibia, in defense of their country. Every country has its history. America too.

I was quite taken with your three daughters in the film. They are highly articulate, interesting and intelligent women. They form a parallel story here and one of the most fascinating moments is when they describe how you gave them an artistic life; encouraged them to look outside of Detroit and into art, etc.

Rodriguez: Oh, thank you very much! They are mine. Their moms had a lot to do with their direction. I could provide some things, but I could not provide other things. But Detroit, being the city it is, it’s good to know there are a lot of things outside of Detroit. My daughter Eva, is a solider with twenty years in the army, and a medical officer in Desert Storm—the first one—and has been at the tearing down of the Berlin Wall. She has been in Korea and Germany and has been stationed all over the world. She called me and said, ‘Dad, they are demonstrating for water and electric rights here.’ So they are very involved. We are all on a mission.

Malik, I believe you said Rodriguez’ story is a ‘testament to the power of the arts.’ Explain what you meant.

Bendjelloul: Yes. If you think about what Rodriguez did, sitting at his kitchen table writing songs, sort of a like a remote control that he didn’t know he was aiming, he changed society just by writings songs. How could it be more important? Young people listen to those words and get excited, and he really was the first inspiration for the white, South African anti-apartheid movement. He changed the world.

We’re talking about music changing the world, but do you think movies have the power to do that as well?

Bendjelloul: Yes, sometimes, depending on the subject. I think music even more because it gets inside you in a way that film does not always. Music you can listen to hundreds of times.

It’s fascinating this story could have happened, but not that hard to believe given that the internet didn’t exist at the time, and South Africa was a contained place.

Bendjelloul: It was a country that was completely isolated because of the apartheid system. A man was living in a house without a telephone. No internet, no forums and no communication.

Rodriguez: Well, Voltaire said, among many things, that the pen was mightier than the sword. And today, I think the camera is mightier than the pen because it can actually capture so much. It captures a moment in history. And now with the internet, you cannot hide this information. And censorship is also the core of certain lyrical content, and if they don’t want you to hear it and they don’t want you to think it, then that’s not government.

When we hear the music throughout the film, we almost cannot believe it was not a huge hit. What was the reason, do you think? Too much competition from Bob Dylan, Lou Reed and others? Was race an issue?

Rodriguez: Oh, yes. I want to say this, because in the 70s there was a lot of music being released. Carole King’s Tapestry was just coming out. Elton John was just surfacing. Fleetwood Mac had just released Rumors. There was a lot of product being released. They didn’t see it or didn’t hear it. There was a lot of talent coming out at that time.

Bendjelloul: And Rodriguez was an Hispanic name. At that time in America, you weren’t allowed to play this music if you were Mexican. It should be mariachi music; something that they understood. And this guy was seriously challenging the Bob Dylans, Rolling Stones and the Doors. That was not a role you were allowed to play at that time.

Are you touring now, Rodriguez?

Rodriguez: Yes, sir. We just did Jersey this past month and we are slated to go to the West Coast today. We are following this film, and it was picked at the Sundance Film Festival, the theme of which was film and music. So we are carrying on that theme. This film has excited my music career and so we are touring.

Had Cold Fact been a huge hit, how do you think your life would have changed?

Rodriguez: Had it been a hit? It’s like, ‘If only JFK had not driven in a convertible.’ It’s that kind of thing. Well, this thing indicates to me that it is never too late or too early. It’s great to be here in Chicago. You have a lot of political history here. Not that different from Detroit, where we have a mayor who did a little time already and is going to do a little more.

I’m also from Michigan—a town called Muskegon.

Rodriguez: Oh, Muskegon! I worked in a laundry for 5 years and we used to deliver there with our trucks. I am very familiar with Michigan.

There are some hard times going on over there economically.

Rodriguez: Yes, and a beautiful area. But a lot is happening in Michigan. And even the ‘contender’ for the presidency, his father was governor of Michigan. So people who are sons of these affluent people… Gore was the son of a senator. I can relate to Obama, with my poor, working class background. And I am for positive change, not these opponents of progress, you know? I’m a musical politico. I like the Dixie Chicks. You have three girls who all sing and play an instrument and are political. If they can get down on that, come on. Politics is about ‘power, which is nothing. There are more of us poor people than there are the rich. And I am for change. I am for saving social security and getting people free from that idea. It helped us out with Roosevelt. I have not forgotten that time period either. And the reason why it’s important to remember World War II is because it happened in the modern states. Everybody had refrigerators, and the technology then was radio. It was just being invented. So again, America is at the forefront of technology, creating the internet. Americas are very inventive, and I think it will come to the point where we can fix it. And I am for that kind of fixing.