The Hollywood blacklist gets a superfluous treatment in Jay Roach’s Trumbo, a too much, not enough examination of Tinseltown careers destroyed by MCarthy-era communist witch hunts, and one—screenwriter Dalton Trumbo—who rose from the ashes even while his personal spoils lingered.

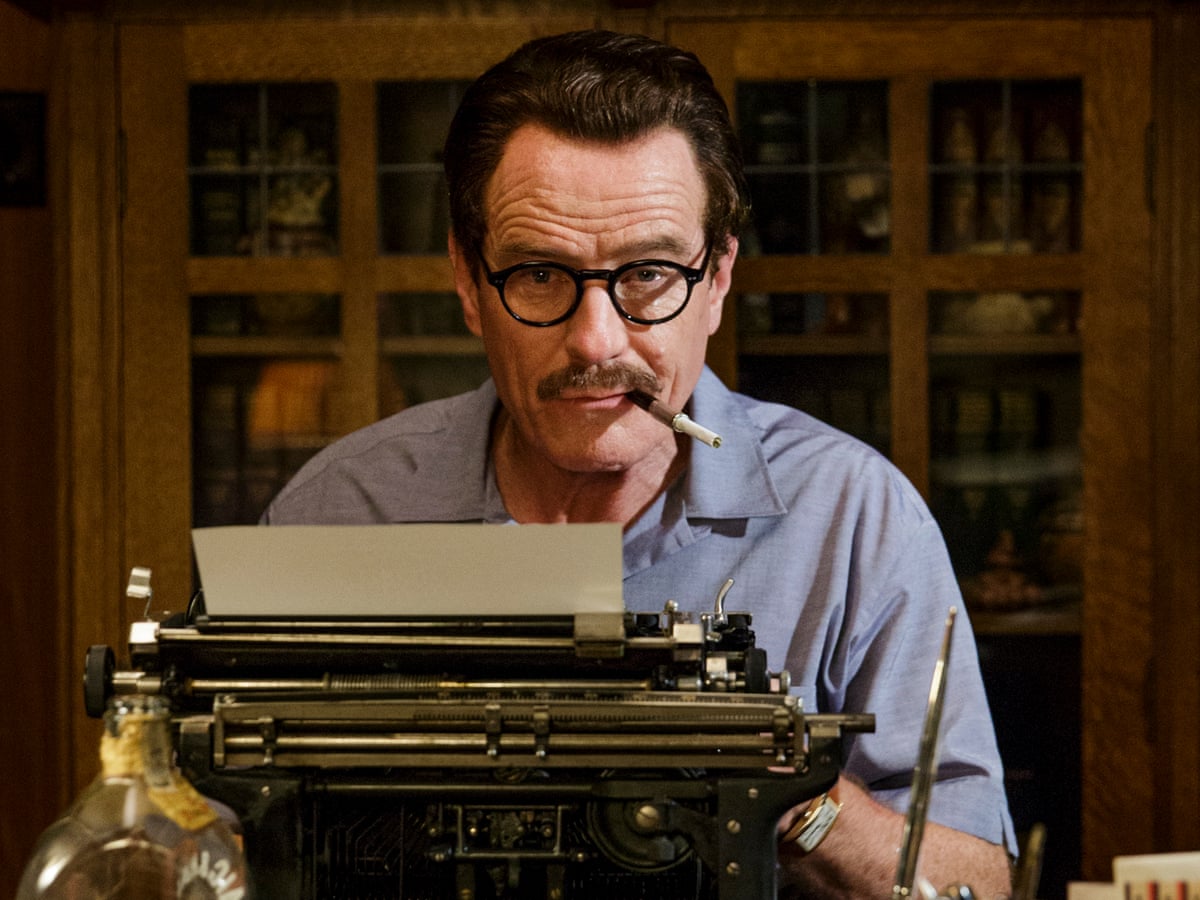

As directed by Roach, it’s a well intentioned if oddly unmemorable movie, led by a nuanced Bryan Cranston as the beleaguered screenwriter whose talent ultimately found a way to surreptitiously thrive even after his name made him an industry pariah.

Yet good intentions aside, Roach’s direction of the two hour picture and its screenplay, by television writer John McNamara, are largely by the numbers, and might have felt more suited to the smaller screen. A richly compelling biopic this is not; rather, Trumbo plays like a who’s who Hollywood travelogue more than a serious examination of democracy gone awry. In other words, the style and tone pull punches.

Celebrated late 40s studio scribe Dalton Trumbo (Cranston) makes no secret about being a Communist (a party he naively joined in the 1930s), and the pensive mood in Hollywood on the eve of the infamous congressional hearings has everyone in town on edge. This is especially true for what would later come to be known as the Hollywood Ten, about to be ejected from their careers as actors, writers and directors.

Like many other artists, Trumbo was named an enemy of the United States by the House Un-American Activities Committee, stoked by hysteria over escalating Cold War fears. The committee’s notorious hearings formed the blacklist, composed of scores of innocent Americans facing accusations of sympathizing with the “Reds,” which as we know was a complete fabrication.

When we first see celebrated screenwriter Trumbo on a movie set he is still a beloved industry player, providing dialogue to star Edward G. Robinson (Michael Stuhlbarg) and on the rise as the most prolific—and nuanced—writer in the business.

With extensive exposition, McNamara’s screenplay spends a healthy amount of time establishing the brewing tensions between Hollywood honchos bent on weeding out “traitors” Trumbo and fellow communists, including a distracting and out of his element Louis C.K. as fictional writer Arlen Hird.

Leading the smear campaign are star John Wayne (David James Elliott) and gossip columnist Hedda Hopper (Helen Mirren), who succeed in spades at ensuring that Trumbo and others are put out of their jobs and homes.

It isn’t long before Trumbo, the screenwriter of Kitty Foyle and Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo, is called to testify before the committee, where Roach uses a rather passé technique of combining real-life footage with his movie scenes, after which Trumbo is jailed for contempt. But as far as Hollywood is concerned, his sentence isn’t martyrdom, at all, but rather a punishment befitting his crime (of which there was none).

Leaving behind his gently supportive wife (Diane Lane, terrific) and children for a stint behind bars, Trumbo reemerges determined to rewrite the rules, beginning with an Oscar-winning screenplay for Roman Holiday, for which he convinces confidante Ian McLellan Hunter (Alan Tudyk) to take credit.

Soon John Goodman shows up as chief of the exploitation studio King Brothers, and before long Trumbo and his fellow blacklisted pals are writing scores of B-movies under pseudonyms, slowly finding their ways back into the business. It certainly helps that Kirk Douglas (Dean O’Gorman) enlists Trumbo to re-write Spartacus and Otto Preminger (a funny Christian Birkel) follows suit with Exodus.

Absorbing story, yes. Movie? Not so much. Disappointingly, there is something too safe about picture; something Hollywood-glossy, affectionate even, when it should be more of an angry indictment. Roach pitches the film’s tone as one of entertainment, fun even—and that’s a miscalculation for such a serious subject.

Of course, Trumbo’s raison d’être is to draw contemporary parallels to our similar fear-induced era, where, for example, a Ben Carson would deny anyone of the Muslim faith the opportunity to lead our country and there are still laws on the books allowing many to be fired without due process simply because they might be gay or otherwise. In today’s world, where heads now roll and blood is spilled largely in the name of political correctness, there is something less than surprising about the dismantling of a career, and life, over individual and personal beliefs.

Cranston, one of the greats, struggles to find the right pitch for Trumbo, sometimes exaggerated and comic, never less than theatrical, then deeply tragic in the film’s final scene. His deliberate elocution adds to the largeness of the portrait, and his scenes with teenage daughter Elle Fanning strike tender notes. At times, it feels rich, moving even; at others, too broadly drawn.

Like the film.

2 stars.