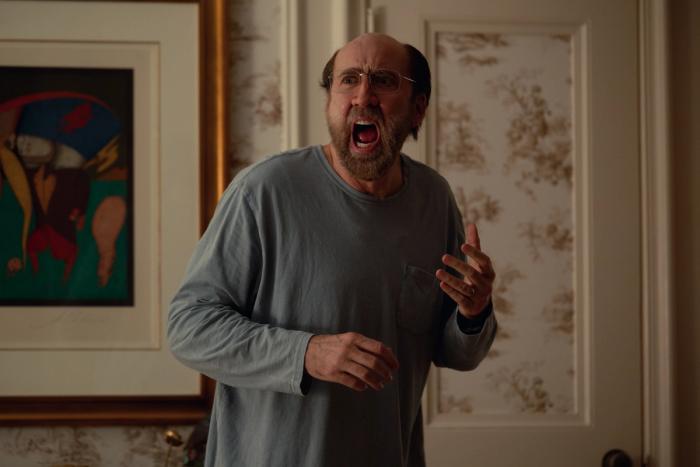

In the inventive and frequently surprising Dream Scenario, filmmaker Kristoffer Borgli crafts a potent critique of flash-in-the-pan viral fame and our societal fickleness in making instant celebrities before breaking them as casualties of fifteen-minute brand recognition. The ever welcome, inspired Nicolas Cage stars as a milquetoast college professor who inexplicably becomes a fixture of the collective unconscious, comically invading our dreams which ultimately, for him, proves an inescapable real-life nightmare.

Borgli confidently trades on inventive dream sequences, cultural satire and middle-aged malaise, deftly balancing tones in a narratively and stylistically unpredictable picture elastic enough to incorporate comedy, drama, science fiction and even a bit of horror. I recently caught up with the thirty-eight-year-old Norwegian filmmaker at Chicago’s Four Seasons Hotel for a chat about his ambitious new outing, one of 2023’s most enjoyable movie experiences.

A good place to start may be to talk about your lead actor. I don’t think it’s lost on anybody that he is an American institution first, and second may be an actor slightly symmetrical to the character he plays in the film having gone way up, been taken way down and is now back up again. I believe he recently stated that he gave you full control of the performance, as if you ‘had a remote control over him.’ I find him almost magical in his range of the abilities that he alone seems to have, including equal dexterity with all manner of comedy and drama, sometimes turning on that dime in the same film. He makes Dream Scenario very funny but also heartbreaking. Can you share a bit about him either as a brand or the perhaps the man that you worked with?

KB: Right. I mean, as soon as he was involved, which was a true blessing, the project suddenly had another layer to it, which was that we were dealing with a man who’s become sort of like a myth in the culture. And he’s probably already in people’s dreams, you know? And then the challenge became one of not wanting the audience to just see Nic Cage because we were talking about someone who, on paper, was an ‘unremarkable nobody.’ And that demanded shaving off his charisma and recognizability, and we had to work together in terms of finding Paul Matthews. He brought many ideas to the table. I had some. We sort of found the character together. And on paper he’s supposed to be a boring character, which is opposite of Nic Cage. But he stayed true to that truth of the character while also bringing all of these very exciting and eccentric choices in body language and mannerisms that were just pleasantly surprising.

He can make a special moment out of an ordinary interaction. For example, the scene near the beginning of the film where he is dining with a former girlfriend and he says to her, ‘My wife thought you were interested in me.’ And she says, ‘Why would she think that?’ His reaction to that barb is perfect, as if to consider, ‘Well, why wouldn’t you be interested in me?’ Shifting gears, this feels like a very modern social comedy, raising topics like cancel culture, called out in one scene. At another juncture there is a funny arrow slung at the notion of triggers and safe spaces. Those things must have been on your mind. I mean, certainly the whole notion of making somebody an instant media figure also informed your last film, Sick of Myself.

KB: Yeah, I mean, it’s first and foremost- I always wanted to make a movie about dreams. That’s been on my mind for probably 15 years. Even before I knew how to write a script I knew that the best location of anything is inside someone’s dream. And here was this idea that played with the Jungian concept of the collective unconscious. And I came to realize that the collective unconscious is something that we’ve made true in our modern life by this hyper connected way that we live. We are in each other’s heads more than we are physically present with each other. And we all are nurturing this personal brand online, which is also the Jungian idea of the persona, or the curated and presented self. And the presented self can take on a life of its own. It has already done that with Nic Cage. And it happens in this movie with a person who has his image appear in everyone’s dreams. Everyone sees him slightly differently and people have different expectations of him, and he comes to realize that he can’t meet these expectations and ultimately hates or rejects them.

This becomes a problem for him, his life ruined by the life of the persona, which is not necessarily a modern idea as the Jungian concept was of course before anything like social media. I think people will very easily see that critique; it does not require me to push it hard. So I stayed pretty true to what I thought it would feel like for the person, a sort of antiquated man who has an idea about recognition as a healthy thing toward which we should all strive. And then realizing what that recognition can look and feel like in the modern world.

That was the movie and the comedy, to me. That’s how I orchestrated this whole path for the character. I think people read into that and see their own versions of what this movie is about and may reduce it to a message about something else that just happens to be in the movie. This takes away, I think, from the complexity of getting to explore the character-dream phenomenon, and how people react to it. For Paul, capitalism co-opts it and turns it into a product. It is ultimately a character study of a man who slips on conceptual banana peels, one after the other, trying to stay true to his integrity and to manifest himself as a successful man worth celebrating—while not really having that much to contribute.

Hence his inability to manifest himself. This guy may very well be capable of writing a brilliant book but he may be just locked inside himself. Like many people, he sees others around him become successful. Here is someone who has gotten to a certain point in his life by just being average and never trying that hard or truly self actualizing. He may very well be gifted, but that remains undetermined. He thinks he will be able to finally realize his potential when he meets with the Thoughts agency and says, ‘I really want to talk about the book.’ Essentially, ‘I want to talk about who I am.’ And this whole idea of the mass commercialization of his already established brand, this dream entity, means the agency is uninterested in deviating from what is able to be easily packaged. Paul himself is not marketable, even though he may well be a talented, substantive person. Those qualities, ironically, are not going to be on brand or on message, right?

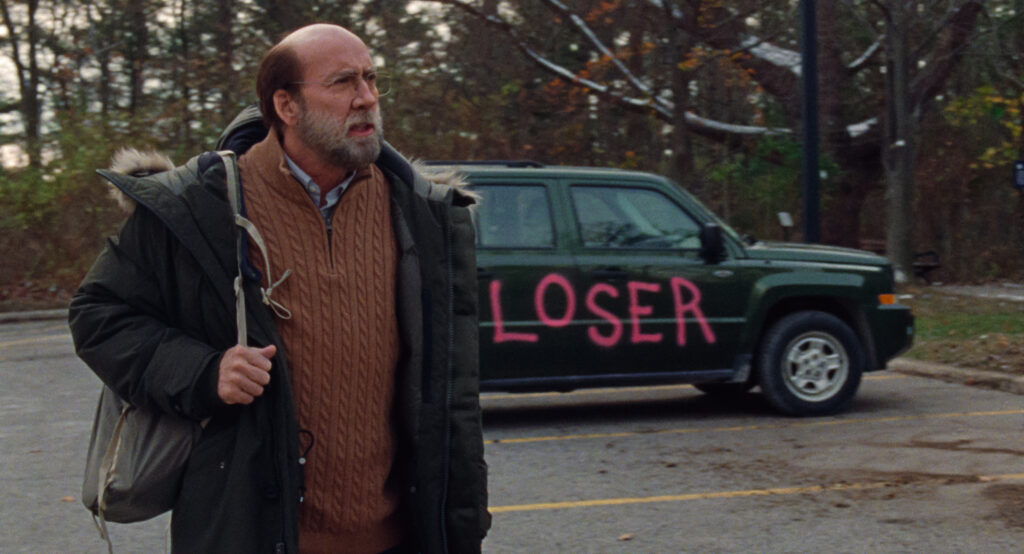

KB: Exactly. And that’s the thing—we’re becoming brands. And the idea of a brand is that it’s something that you can easily understand, but it can’t change. A brand’s idea has to stay true to itself. We as people need to change our positions when met with new facts or realizations like, ‘I thought I was really talented but I’m not being received very well. Maybe I should change something.’ But brands keep pushing a fixed idea of who you are. And I think in that very difficult meeting he begins to realize that he has already become a brand and he’s not in control of it. And he tries to steer that ship away from that brand and it’s impossible. He can’t change it. He can’t suddenly make himself the brilliant academic because he is now famous for being in people’s dreams, and that’s the end-all-be-all of his personal brand.

I found his trajectory to also be a commentary on how we make people famous and then can’t wait to tear them down. We tire of their ‘brands’ quickly. We’re very happy to make an instant celebrity out of somebody and shoot them to the top for one brief moment. And then we’re very excited to see them fall down. Paul is a guy who gets this one moment in the sun. And then there is no good grace afforded to him and we just take him down.

KB: Yeah. I was thinking of something that felt like such a genre idea; a sort of cultural artifact that belongs in The Twilight Zone or an H.P. Lovecraft novel, and to take something like that, rip it out of the genre and then place it in our reality to see how people respond to it. I thought it was comedic that even this phenomenon, one that doesn’t seem to be anything but mysterious or exciting, could quickly become a culture war issue and that Paul could become controversial; that he could become yet another example of this sort of dumb, viral, 24-hour fame. Because of this we can no longer see the exhilarating, magical, supernatural, metaphysical thing that’s happened, and marvel at it and talk about it. Instead, we just immediately make it a debate of right and wrong and which side you are on. I thought that was a comedic premise and I followed it to its natural endpoint.

Julianne Nicholson is sort of the straight man in the movie. It is an interesting performance because she doesn’t bring the brand that Nicholas Cage brings to the movie. She brings a substance and seriousness to her place in her marriage. Obviously Julianne Nicholson, the actress, knows the absurdity of the film’s premise but she doesn’t play it that way. Instead, she plays it at high intelligence. And that’s why that moment near the end where Paul imagines that they are embracing is of real substance. Julianne contributes greatly to that.

KB: Yes. She’s a great actress. She really made the family feel hyper-real and that it had stakes. She created a recognizably safe part of the family, setting the foundation of that household. She makes you root for them as a couple and believe that there’s something in this family worth fighting for and also truly at stake to lose. She makes it loving and believable and warm and emotional. She’s not talked about enough and what she brings to the movie gets almost overlooked because at first glance, the movie is very much a character portrait of Paul Matthews, and Nicholas Cage playing him is kind of the focal point of our attention. But what she does here is truly wonderful. She is such a great actress.

If you could enter anybody’s dream and plant an idea, who and what would it be?

KB: I think it would be fun to go into Nicholas Cage’s head and fuck with him a little bit.

You’ve already done that though!

KB: Right. He started appearing in my dreams as soon as he was on this project.

As Paul or as Nicholas Cage?

KB: As Nicholas Cage. Actually one dream that I remembered vividly was he was about to come to Toronto, where we shot the movie, and we had decided that he was going to be bald in the movie and look like an average suburban dad and that was very important. In my dream he showed up with spiky K-pop hair that he refused to change. He was like, ‘I’m going to have this huge, spiky K-pop hair in the movie and you can take it or leave it.’ I had no choice and felt he had ruined the movie and it was a nightmare. So Nic Cage was like a nightmare experience that I had before shooting the movie, but in reality it was, of course, a pleasure. It was a dream come true.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.