This Friday, November 17, at the Gene Siskel Film Center (8pm; tickets here), Chicago-born filmmaker and Hollywood director Andrew Davis returns to present his fledgling 1978 film Stony Island—his first as a director, shot on period Chicago’s gritty streets as a guerrilla endeavor of craft and charm—back to the big screen for a proper, one night only screening, the first since its 1978 theatrical release. Both Davis and brother Richie, who stars in the film, will be on hand for a post-film Q&A.

One of the most authentic pictures ever to be shot in urban Chicago, Stony Island, a musical drama charting the struggles of a handful of young denizens eking out lives as musicians against an often challenging backdrop, is a time capsule explosion of a movie. Featuring original R&B and soul songs and performances, notable musical and on-the-rise acting talents and a portrait of Chicago from a bygone era of south side, Loop and downtown environs, it is loving homage to youth, talent and struggle, perhaps the original “making the band” movie and one starring the director’s talented younger brother, Richie, today a successful Chicago musician.

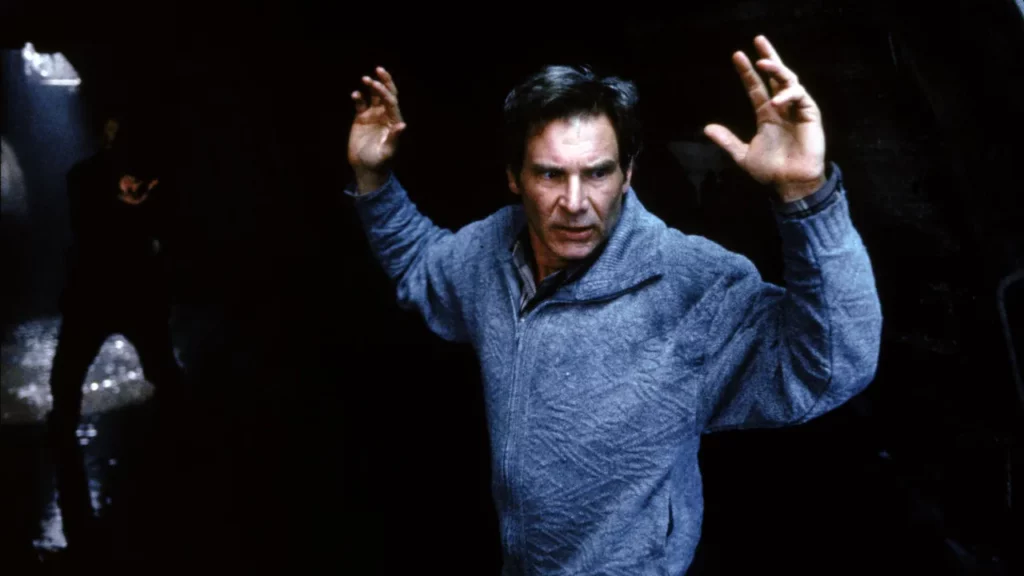

Davis may be best known for 1993’s seminal, muscular The Fugitive, featuring a Harrison Ford-Tommy Lee Jones double act in an action thriller that thirty years on remains one of the era’s best and most beloved. Davis, who graduated from University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign with a degree with journalism in 1968, got his start in film upon being mentored by one of the world’s greatest cinematographers, Haskell Wexler, who showed him the ropes on Wexler’s verité masterwork Medium Cool, shot in Chicago during the tumultuous summer of 1968 during the Democratic National Convention.

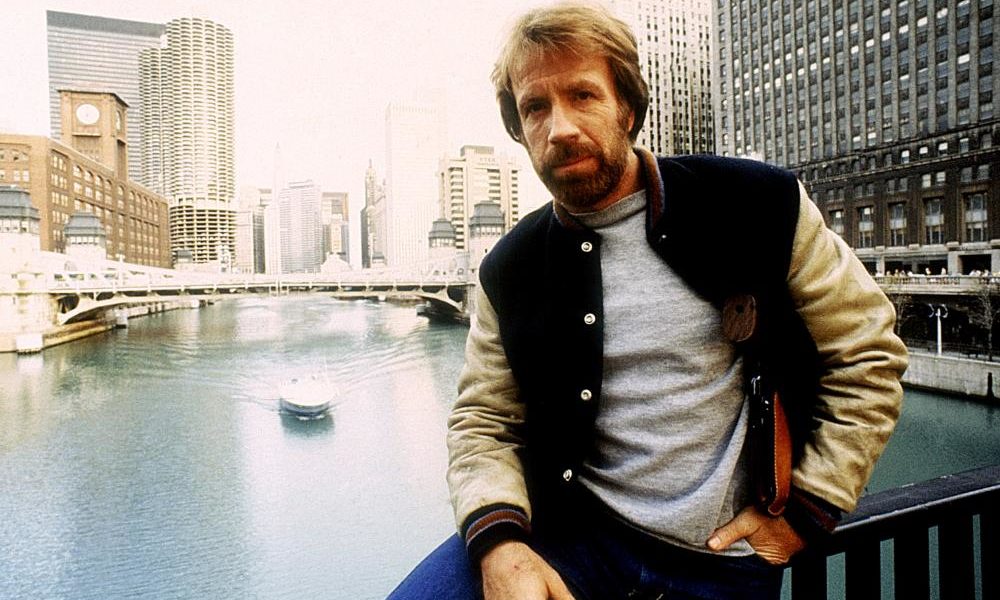

Following was a multi-year stint as a cinematographer on such early 70s genre fare as Private Parts, Hit Man and Cool Breeze and lensing such 80s cult films as Over the Edge and Angel, both of which have significant modern followings. It didn’t take long for Davis to graduate to the ranks of popular American movie director, one whose career may have led him west but who frequently brought Hollywood back to his home city in a string of two-fisted, Windy City-set action pictures including Above the Law, Code of Silence, The Package and The Fugitive in a canon also including Holes, Under Siege, Chain Reaction and Collateral Damage.

This storied career began far earlier on Chicago’s south side, a influential 1950s playground for young Andreas Davidescu and one where he developed a rich feeling for the city’s geography, running the metropolis at a tender age from the south side to the Loop and back, an urban education during one of the most musically creative periods in the city’s history. This singular personal history informs every frame of Stony Island, a lost Chicago classic that never received much-deserved theatrical distribution despite a 2012 DVD release. The picture will also stream November 17 on select VOD platforms and DVD, where it will undoubtedly be discovered by an all new audience.

I caught up with Andrew Davis this week to chat about his endearing first film, taking a look back at its origins and story of an integrated artists’ collective trying to get that ever-important big break. In a wide ranging discussion, we also considered Davis’ career highlights, the state of the movie industry today and, as it turns out, his unlikely connection to my hometown.

Stony Island may be the quintessential Chicago film; it is certainly a time capsule of what we might call a vanished Chicago, or one that doesn’t exist anymore.

Andrew Davis: I don’t disagree, but why do you say that?

Well, it’s a glimpse into a bygone Americana; probably true of most major cities. When I arrived in Chicago in 1989 it was still very much the “old” Chicago. Most of those buildings don’t exist anymore. The Loop and Michigan Avenue are converted into most modern, tourist-friendly areas; old buildings went down and new went up. It’s barely recognizable as the city in Stony Island. The charm is largely gone but it is all over your movie.

AD: Oh, yes. The West Loop did not even exist.

Seeing the film shot in some of those places that look totally different now—Rush Street, Randolph and Lake and the Loop theater district, Michigan Avenue, Merchandise Mart and Chicago Avenue and long gone theaters, hotels and restaurants—is a time capsule.

AD: Yes. In the documentary The Making of Stony Island Rae Dawn Chong says the same. She said when she comes to see Chicago it doesn’t exist like that anymore.

I guess you can’t stop progress as they say.

AD: Yes, but also, there was a lot of stuff that was torn down that should have gotten torn down. And other things that should have been restored.

Yes. Stony Island is somewhat of an homage to your adolescence. I think you mentioned that when you looked at other films of the time, like George Lucas’ American Graffiti and Martin Scorsese’s Mean Streets, you wanted to do something similar for your time and city, growing up on Chicago’s south side.

AD: Yes. I remember as a kid growing up on the south side that my mother would give me a nickel and I’d get on the bus and go from 98th Street to the South Chicago YWCA.

Alone? You were how old?

AD: Eight. By myself! You could do that then. She taught me how to take the bus to South Chicago, which is not a kind neighborhood. But nonetheless, I went to the Y and I got into the photo club. I became the president of the South Chicago YMCA photo club when I was eight. I remember they would take the photo lab on Halloween and make it a spooky thing with a red light, and put spaghetti in marbles and you would have to touch it like you were touching eyeballs and things like that.

Anyway, we traveled. We got on the bus and went downtown. 63rd and Stony Island was the center of a universe for me because there was a ball field right there on the corner of 63rd where there was always a serious baseball game going. Herbie Hancock went to high school a block down the street at Hyde Park High School. I rode my bike by Bo Diddley’s house by Jackson Park. There was a whole world of people coming up to Chicago from the south, being met at a Greyhound bus station. The first Chicago McDonald’s opened there. The Blackstone Rangers ran the territory, you know what I mean? And it was just the beginning. Oscar Brown Jr. was a hero to me—this musician who talked about and wrote songs about growing up on the south side.

So that was my world. And then my brother, 11 years later, my mother got him into Metro High School, downtown, the school without walls. They took two kids from every part of the city and put them in this one school. And they didn’t have classrooms, they would go to the arboretum to study plant biology, the aquarium to study fish—it was that kind of world. So it was using the city as a playground. We had the Museum of Science and Industry; that’s where we went. Every other Saturday we went downtown and got in trouble. We would go in and look at guns and pawn shops and different kinds of things you could only do downtown.

Here in the Loop?

AD: Down on Van Buren. My grandfather was a tailor on Van Buren Street. Downtown was exciting and that was when it was flourishing. It had Marshall Fields, Carson Pirie Scott, Sears and Goldblatts; all big department stores downtown. it was a thriving place. In Chicago you could always get a job. You could always find a job in Chicago. If you were unemployed it was your own fault. People struggled and there was a disparity in wealth, racism and all that kind of stuff. But it was a city that worked, right? I was also aware of the differences and racial disparity.

When I was a kid I remember that a Black family moved into an all-white housing project named Trumbull Park. It was a public housing project. Well, the neighborhood was a steel mill, working class neighborhood and the racism that rose up- there were riots and there were people throwing bombs at this family and it was terrible. I hated it. And so I wanted to do a film about how Black and white people would get along and how music was a common language. And I think that that’s what sort of motivated me to make this movie.

There is this fight in the film, which is the struggle of the working-class artist. Here it plays out literally on the streets of Chicago. As Edward Stoney Robinson says atop the Chicago train platform, ‘The whole world is a stage…’ Artists like those in the film spend a lot of their time on the streets of Chicago because they have to make a living, right? So if you’re a young artist in Chicago coming out of art school or whatever, you spend a lot of time on buses late at night. You spend a lot of time on trains. You spend a lot of time on the sidewalk. You spend a lot of time running from this job to that job and then to rehearsal later at night. This movie captures that rough and tumble combination of what it means to really be an artist hand to mouth in a city. The idea that you want to play the saxophone more than anything, but what you really have to do is wash windows to make a buck in order to pay the rent. And that collective that you mentioned a minute ago is more the focus that the racial integration of it. That part is never discussed. There’s no kind of racial dimension discourse in the film even though lot of the music is what might have been called Black music of the time, right?

AD: Yeah, well, the film didn’t talk about race. It wasn’t an issue in this movie. It was just people just getting along with the mentorship of this older man whom they revered because of his ability to put people together and teach things about music. And it wasn’t because he was rich or because he a lot of cars or anything like that. There was a value in a kind of humanity that was a very positive kind of thing to portray.

Can you talk a bit about Gene Barge’s work in the film as that instrumental mentor? He is still with us today at age 97.

AD: Yes. I am in touch with him. He has been a dear friend for years. I was just at his daughter’s wedding. I put Gene in The Fugitive. He’s got a great part: ‘The good doctor’s skin is under her fingernails.’ And he was in Under Siege. He’s in Above the Law and Code of Silence. Whenever I needed a detective I would say, ‘Gene, be a detective.’ And he is somewhat of a legend because he survived so many different strains of the music industry, which is not an easy industry. People were exploited, their publishing was taken from them and kinds of stuff. I’m very grateful that Chuck Stepner, a producer at CBS, introduced me to Gene Barge. Chuck is coming to the screening. There’s a lot of history there.

Let’s talk about the music. During production and given the small budget, it was not possible to license music, so you had to create your own songs. That lends to the authenticity of us feeling as if we are meeting this band for the first time and hearing brand new music that has not been played by anyone before. Many of those songs, like City Lights and South Side of Chicago are indelible. You created all of these for the film and they never existed anywhere else other than this film, right?

AD: I think I bought the rights to a couple of great songs. Everything Must Change was already a song. But yeah, Rae Dawn Chong and Susanna Hoffs wrote South Side of Chicago. Stoney Robinson wrote City Lights. And the lyrics, I listened to them today, man. They are still so relevant—people trying to survive, trying to get by in this cold, hard city. People trying to get on, you know? Very relevant. And it made it authentic because it wasn’t like you were hearing proven hits that everybody knew, which The Commitments was able to do. Cover bands are great. My brother plays a lot of great cover band stuff with his band, The Chicago Catz. But we were just lucky that it came together. And there’s a rawness and an unsophisticated quality to some of it. And that’s what the story was about. How do you mold your career? How do you fine tune things?

You mentioned your brother who has a very gentle and appealing quality leading this movie. He’s not necessarily pushing hard as an actor and that is nice and engaging. There’s something very gentle about him and enjoyable. He looks like a movie star. After I saw the film was I thought, well, this guy could make a long list of other movies. But I think he’s pursued music as a career.

AD: What happened is that I pulled him out of pre-med in Champaign to be in the movie and he never went back. And I thought my mother would be very unhappy with it. But as Richie says in the documentary, ‘I’m making people feel good. I’m healing people with music.’ So he became a studio musician. He played on lots of jingles. He met a bunch of great musicians. And after that business sort of wore out and they weren’t doing jingles as much he put a band together called The Chicago Catz, and they are the number one wedding band in Chicago. They are so popular. There might be three Chicago Catz bands playing on the same night. And what’s funny- I think in the Stony Island sequel it should be Richie having to negotiate with the brides and the mothers and the fathers and the grooms and the rabbis and the priests about what they’re going to play and at what time.

Perhaps another Chicago movie right? He also got to have an on-screen love affair with Susanna Hoffs—not a bad deal for being in the movie. And Susanna Hoffs, of course, when we see her and Rae Dawn Chong here, they both went on to be big stars. In Stony Island there’s something fun about seeing people like that at the very beginning of their careers who went on to become big. Dennis Franz as well. But you couldn’t have known at the time, or maybe you did, that you had this collection of people primed for such careers.

AD: You know and you don’t know. If you put a cute, talented kid in a movie, you think something might happen. We didn’t know if the movie would even be to see the light of day and it almost didn’t. And so they had talent and their own sense of pushing their careers.

Stony Island seeing the light of day was difficult right? It got great reviews. It played festivals where it did very well. And then it didn’t get wide distribution. I understand that the title of the movie was changed and it was positioned as a Blaxploitation movie. So the movie never really got its theatrical due. It just sat for decades after that.

AD: It did. It sat until 2012 when somebody did a half-assed job trying to re-release it. But now it’s going to be available on all these platforms, and I hope it will get enough publicity and perhaps Susanna and Chuck D and everybody involved with the movie may sort of to help get people go see it.

You wrote and produced Stony Island with Tamar Hoffs, another Chicagoan. You met Tamar when you made Lepke together, right? She had written the screenplay and you were the cinematographer. Back in the 80s I remember seeing her film The Allnighter.

AD: Her father was Ralph Simon, who was a very well-respected rabbi who worked with Martin Luther King, Jr. He also represented Marshall Korshak, who was the head of the Cook County Committee. Before we made the movie, we went to see Marshall, who called in Eddie Burke, this young alderman at the time who is now on trial, if we had any problems: ‘Eddie, these are friends of mine.’ We didn’t have any money for insurance. We didn’t have any union issues. We just jumped on the train and shot.

So you get on, get the shots and then get off before anybody notices that you’re shooting.

AD: Yeah, we just grabbed shots. It was like people would do with an iPhone today. I’m sure people are making movies like that now. So there was Tammy and her husband, Josh. She was just starting her career and wanted to be a filmmaker, and she made some films afterwards. She was from Hyde Park. And she went to Yale, and Josh was at the University of Chicago also. So they had a real deep connection to the south side of Chicago. And then Susanna’s career just blossomed.

But you didn’t know her in Chicago, right?

AD: No, I met her on this movie, I was a cameraman on it. That was the connection. Tammy’s brother, Carmi, was another kid like Paul Butterfield and Mike Boomfield and several other musicians who fell in love with the blues players of Chicago, and their lives changed because of that. So it was the same story of culture traveling from one generation to another and from one race to another.

Before directing Hollywood films you were primarily a DP; cinematography was your career. I recently revisited a genre film that I love and was surprised to see your name pop up because I didn’t know you had shot it. I’m referring to Paul Bartel’s Private Parts, which is one of my favorite drive-in movies.

AD: Oh, yeah, that was fun.

I imagine it was fun. There’s probably not a scene in that movie that doesn’t have some sensational, lurid element to it. It must have been a lot of fun to shoot those scenes.

AD: Paul was a hoot. We shot at the King Edward Hotel downtown L.A. And I remember we’d go to work and there were people selling blood at five in the morning on Skid Row down there. It was pretty grim. But Paul was great, and a lot of the crew that worked on Stony Island worked on that movie—the same core grip, electric, Tak Fujimoto and camera assistants worked together on it. I shot all these MGM movies—Hit Man, Cool Breeze, The Slams.

Jonathan Kaplan, right?

AD: Yes. And George Armitage. The director (Barry Pollack) who did Cool Breeze became a doctor. He didn’t continue as a director.

So you did continue as a director and you made a whole string of movies in Chicago. Just about any time that you were gonna make an action movie you came back here to do it.

AD: Yeah, well, I did other movies. I shot Under Siege in Alabama, and I did Collateral Damage. I did Holes which was not here. And also Chain Reaction, But I was glad to bring some back here—Stony Island, Above the Law, Code of Silence, The Package and The Fugitive.

What do you think about the city as a character in movies today? It seemed that when you were shooting here there was a renaissance of filmmaking happening in Chicago. Maybe you brought a lot of that with the projects that you did, but now it seems a bit different. I’m not sure what the identity of Chicago is in commercial movies anymore, or if there is one. There seemed for quite a while to be a thriving vision of Chicago in Hollywood movies. I guess for a while it was Toronto doubling for Chicago as well.

AD: I think that Transformers and Batman were shot here. All I know is that we were able to establish that there were really good crews here, great cooperation from the city and a talent pool of actors. So the studios were smart to say, ‘We don’t have to bring all these people from some other place.’ It was cheaper than New York and I don’t know what the tax deals were, but certainly- who’s the big producer of all the TV shows here? Dick Wolf. Dick Wolf has adopted the city as his money bags. I don’t know much about the TV stuff that’s going on. I know they built some new studios here. So it’s developed its own industry. It’s got its own world here. I don’t know what features have been shot here lately, but I think David Fincher’s The Killer was here. But they really didn’t use the city that much.

Not much, I mean, it is kind of interiors for the most part and a couple of sidewalk shots. So when you look across the whole of your career, from making Stony Island to a turning point like The Fugitive, what’s the best part about your job?

AD: Working with really creative people with whom you become close. It is like going to war together. You go through a battle and through that process you become close. Some people I don’t ever want to work with again! But most I appreciated. When I remastered The Fugitive recently I was really touched, especially by James Newton Howard and my editors Dennis Virkler, Dov Hoenig and Don Brochu. I was really touched by what everybody contributed, and then Tommy and Harrison and the cast. You just appreciate the collaboration and the creative process and you say, ‘How the hell did we get that done?’ Peter McGregor Scott was such an amazing producer who was able to help the train crash be what it was and help get that battleship and the submarine to work; all those kind of things. You have an idea of how you want something to look and he’d say, ‘I get it, Andy. Let me work with you. We will figure it out. Do you want to do this or that?’ And it works out.

I wonder what your thoughts are on the industry shift in the last decade or so where movies like The Fugitive, for example, that were not cheap to get done but not as expensive as a lot of films are today, were still made and appealed to commercial mainstream audience that would show up for them. Now we have this sort of thinking that—and I don’t know if I agree with this—most of the adult level stuff is better on streaming or that people wait to stream movies. An entire layer of movies that used to exist are missing in the industry now that used to be thriving.

AD: In theaters, you mean? That is probably true.

So a very commercially successful director like you would be an anomaly in this industry today, because Hollywood doesn’t make movies like yours as much anymore.

AD: Well, we always say they don’t make movies like this anymore. Jaws sort of started it, when you think a movie that can make that much money, everybody asks, ‘What’s my Jaws or Star Wars going be this year?’ But the thing that’s really killed it was the advertising budgets, because you’d have to spend $50 million to open a picture, to buy the air time, and to buy press. Now it’s a different world of advertising. In the old days everybody knew your movie was opening on a given Friday night. There was a feeling like, ‘We’ll go see that this weekend.’ Today there are so many choices. We had four major networks then and now there are 50 channels to watch. So you can’t guarantee that you can get someone’s attention and they’re going to want go see it. Everything just sort of got dispersed, and there’s an equity to that because anybody can be a filmmaker and put their stuff out in the world. But how do you get people to want to show up? How do you get people to show up on Friday night to see this movie? How do you communicate with them? You are not going to buy ads on TV. Right now I’m talking to you and we’re talking to the people. But how do we get people to know that it even exists, and say ‘I think it’s worth going down and spending 13 bucks to buy a ticket to see that movie now,’ when they can wait and it is going to be available next week online.

Yeah. So even if you think about, remember when we used to have five Academy Award nominees, and everybody wanted to see those movies because they were the five, right? And you’d have a conversation at the water cooler, whatever, everybody would just make a point to see those and they’d be part of the culture. Movies aren’t really part of the culture in that way anymore. It’s harder to get them to be part of the culture. So when something strikes the zeitgeist like a Top Gun: Maverick or a Barbie, the question is why and what is the formula? I don’t think anybody’s really figured that out. It used to be that you could just make a solid movie with a bankable movie star and everybody wanted to see it. People would show up for it. And I don’t think it’s that anymore. I don’t know if we have stars that people will show up for anymore. I don’t know if they even matter to ticket buyers. Can you think of anybody that somebody would rush out and buy a ticket to see in a movie?

AD: Today?

Yeah.

AD: Taylor Swift.

That doesn’t count. (Laughter)

AD: I don’t know. Once again there are so many choices. I mean, you see people at the tops of lists that I’ve never heard of before. Actors who come from TV shows I’ve never watched who are now on this list, or their IMDB numbers are way up beyond stars that should be ahead of them. So I don’t really understand. I just know it’s overwhelming the amount of choices people have. And I think that people have trouble keeping up. I’m amazed that my forty-year-old children know music that I never heard of. I’m glad they know some of my music, and my wife’s music, but there’s just so much going on today. It’s hard to keep up.

We’re overwhelmed with information. But we sort of have done that to ourselves. What’s the first thing you do when you wake up in the morning? You reach out and pick up your phone, start scrolling before you even get out of bed, and might stay in bed for half an hour doing that, right? And what’s the last thing you do before you go to bed? The same thing, right?

AD: What do I need to know? What am I missing?

Right, fear of missing out. So you’re right, the world has changed, but I lament that it has squeezed out independent films; tiny films like the one we’re talking about today. Remember when Soderbergh made Sex, Lies, and Videotape back in 1989 and that was a big deal? It came out of Robert Redford’s arguably purer version of Sundance at that period. Then we had the whole 90s’ era where you could have a blockbusters like yours and tiny indie films as well. They could all coexist and there were audiences and support for them.

AD: It is interesting you mentioned it because Stony Island was invited to the Salt Lake City Film Festival, which was the precursor to Sundance; (Redford) sponsored it. And that year there were six independent movies. That’s all. So we were lucky and got a little bit of attention because there was nobody else to get the attention.

But you weren’t making that movie to necessarily break into Hollywood. Today I feel like most young filmmakers are making films and going to festivals to break into the commercial industry so the films themselves seem less personal. A few eras ago there were much edgier films, for example in the early 70s like Five Easy Pieces, The Last Detail, Easy Rider. Young, new, fresh voices making individual statements for very little money. They wanted to talk about male identity in a different way. They were edgier, they hadn’t been seen before.

AD: Yeah, but those movies had distribution from Columbia Pictures. Those guys had a deal—BBS, Bert Schneider; producers who had some weight. And they said, ‘We’d like Nicholson, Hopper and Monte Hellman’ or whoever else was involved in directing. And so the old farts at the studios said, ‘We don’t understand this crazy business. Maybe these young people can teach us something.’

‘Here’s a couple million dollars, go do it.’ Today it seems like we might not get a film like Stony Island at Sundance because the goal now is to get to the festival and sell your movie for $10 million. I’m not sure that you were thinking that when you made Stony Island.

AD: Well, I don’t know. I think if this film came out today and I was unknown and my name was Andreas Davidescu rather than Andrew Davis, and somebody said, ‘Holy cow, they did this incredible period movie in Chicago, look at this. It’s about race and…’ you might get a lot of attention. And I think that people are supporting people of color and women directors, which is okay! There’s a lot of talent that’s emerging that is worthwhile and getting a chance. Yet there is something missing in terms of going to see a movie that has a good story that’s not ultra-violent. The level of violence just makes me sick. I mean, even these actors who I love are in movies where people are pounding at each other for five minutes at a time.

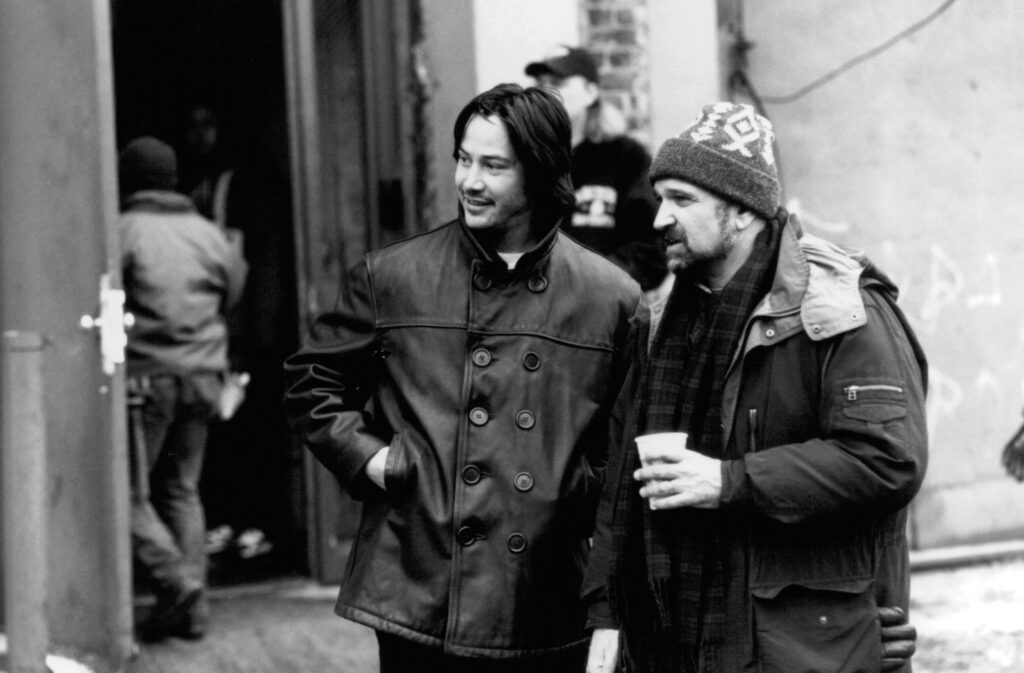

Like the most recent John Wick film.

AD: Yeah, Keanu, who I love. But why does he do that? Why is that what he wants to make a living doing? I guess it’s opera to him; high-fashion opera martial arts or something.

But in a way, it’s also because we as an audience, not necessarily you and I, but just collectively the audience, demand something bigger and better every time. And so there’s a level of desensitization around that that is sort of like, ‘Well, if we killed 100 people in the last one let’s do 200 in this one and let’s make it another hour longer.’ So bigger is better and that means, in these movies, more bodies, right?

AD: But at the same time, there are people who pointed this out to me recently because of The Fugitive. They know it’s not real. They know that CGI and digital effects are making all this look like it’s happening and but they’re really not flying out of the airplane and landing. We got away with it jumping off of a dam with a dummy and a train crash that really happened. But I think CGI has sort of made the real and the unreal world- and now, with Russian interference in our elections and manipulation of the media and being able to put someone’s face over someone else’s body, you don’t know what you’re watching.

What you’re saying in a way about the use of digital technology, for example, in blockbusters- there is now a point where I think we know that it’s bullshit when we’re watching it. We know there’s very little at stake that it isn’t real. These are not practical effects. They’re not chase scenes that are happening on the streets of Chicago. They’re not stunts that people are doing. They are hanging on wires against a green screen. And so there’s really nothing at stake as you’re watching it because you know that it’s all fabricated digitally. If you look at any average superhero movie, you’re going to have a sequence where a hero and a villain have a big showdown and one of them is going to kick the other one into a building that crumbles, and he’s going to stand up then do the same thing to the other, and that’s going to go on and on. And you’re not invested because you know there’s nothing at stake. It isn’t real. The films you made in Chicago feel very real. Those are actual chases, jumps and fights. I miss the fact that we don’t have those movies anymore and that’s why I choose in my spare time to revisit that era and watch them, often over and over.

AD: I’m fascinated by your understanding and your history of these exotic little films like The Final Terror and Private Parts and…

I grew up in the local drive-in. I guess in the early and mid-80s I spent every Friday and Saturday night at the local drive-in seeing triple bills that were horror films, teen sex films, Bruce Lee and action stuff. That drive-in is still there. It’s a four screen drive-in.

AD: Where is this?

Muskegon, Michigan.

AD: Do you know that I know about Muskegon, Michigan?

No. What about it?

AD: The middle finger. It helped me get out of the army. No, no… South Chicago YMCA’s Camp Pinewood is in Muskegon, Michigan. And Richie Marks was holding the end of the canoe and it slipped, and he dropped it there was a nail and it ripped my finger open. So I have stitches here. So when I went to the draft board they said, ‘Do you have any scars on your hands or feet?’ ‘Right here!’ I canoed and we went down the Pine River. It was beautiful.

It’s a beautiful place and the drive-in is still thriving. It has four screens as it did when I was growing up. So if you would adjust all the car mirrors you could see every screen. Unbelievable. So I was looking at The Final Terror, Private Parts and every exploitation movie I could. It was a great genre film education.

AD: You know, in those days, they determined whether they would make the movie based on the poster. Sam Arkoff—who produced The Final Terror—would say, ‘Give me the poster!’

I have a poster collection from that era too. Bronson movies, slasher films and the like, and in nearly every case the art is so much better than the movie. When you sit down to watch the movie you usually say, ‘Why am I watching this thing? This isn’t any good—but the poster is a work of art.’

Get Stony Island tickets here.