A recent UCLA survey of Gen Z moviegoers revealed a distaste for nudity and sex on screen, a u-turn from the boundary-pushing films young audiences lined up for after the Hays Code’s fall in the late 1960s, like the X-rated Oscar winner Midnight Cowboy and frank exposés including Last Tango in Paris and Carnal Knowledge.

For decades, such raw intimacy was on display in American cinema, but those days are now mostly gone. Sure, we may see the occasional put-on titillation of, say, a 50 Shades of Grey. But post-#MeToo, Hollywood productions and actors now operate under strict rules, from ironclad contracts to intimacy coordinators. Maybe it’s just no longer worth the hassle.

Yet sex in the cinema may be making a comeback. In 2023’s Poor Things, Emma Stone delivered a funny, exposed Oscar-winning turn as a Victorian-era concoction reveling in knowledge and pleasure. This year, Sean Baker’s Cannes winner Anora took on sex and class through the ribald lens of a Brooklyn stripper and working girl.

Now comes the corker—Halina Reijn’s Babygirl, an engrossing examination of female desire and power in which a galvanizing Nicole Kidman single handedly brings sexy back as a commanding Manhattan CEO whose repressed urges erupt like a dominant second self. The winner of this year’s Volpi Cup (Best Actress) at the Venice Film Festival, Kidman leaves no vulnerability unexposed and no vanity intact. There’s a charged quality to the character and performance, like a double-dare challenge accepted by an A-list Oscar-winner showing us, as if we did not already know, that she’s afraid of absolutely nothing.

Add equally intrepid Dutch writer-director Halina Reijn (Bodies, Bodies, Bodies) and you get a psychologically penetrating movie about voracious desire, flipping consent and gender roles on their heads. There are brazen, taboo scenes in Babygirl that are potentially humiliating (for character and actress) but never gratuitous; Reijn gets that far inside the psyche of her polished construct of a self-made woman ripe to be dismantled.

And is she ever. Kidman stars as Romy Mathis, the tight ship leader of a high market cap company on the cutting edge of warehouse robotics; it’s a thriving business built solely on her vision, and she occupies its highest seat and public face. Live-to-work, 24/7 Romy is beloved by her young staff, and has a reputation for approachability and emotional intelligence in a world driven by AI. She’s the top of her game.

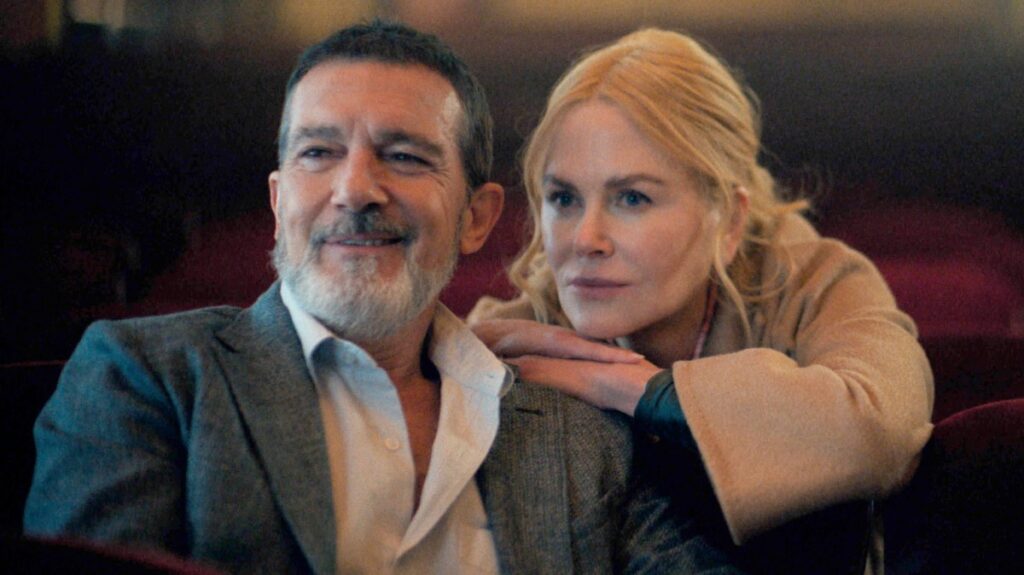

Yet in the picture’s opening scene—cleverly shot upside down—she fakes an intense orgasm with her Broadway director husband, Jacob (Antonio Banderas), before furiously rushing to her laptop to get off solo to domination porn. As she’ll viciously weaponize later, Romy has never been able to achieve orgasm with her spouse, a neuroses hidden as a deep, dark secret. But what is the problem, given that her husband is caring, tells her “I love you” during sex and is, after all, Antonio Banderas?

Enter brash young intern Samuel (Harris Dickinson) who lights Romy’s erotic match, and almost instantaneously the too-big-to-fail boss finds herself in a push-pull seduction that strikes like a thunderbolt. After Samuel sizes superior Romy up in the office kitchen, ignoring hierarchical protocols and demanding she become his “mentor,” just who is mentoring whom (and at what) will be the thrust of what follows. “I think you like to be told what to do,” he presumptuously tells her, throwing the big boss off balance.

Romy knows their connection is “wrong” and while she keeps pushing back on Samuel’s “completely inappropriate behavior,” her ruse gives way to erotic gamesmanship that trumps both judgment and, ahem, all HR guidelines. Why put herself in such crosshairs? “Something has to be at stake,” she explains, to achieve sexual fulfillment and she needs to be powerless and dominated. And the potential loss of marriage, career and stability is a pretty masochistic motivator; she’s got everything to lose and Samuel, nothing.

Samuel, crafted by Reijn as a bit of a puzzle, serves as a catalyst for Romy’s sexual discovery. Their flirtation quickly escalates into an encounter in a shabby hotel room where he not only makes her crawl on her knees and stand in a corner as if in punishment, but also gives her the most intense orgasm of her life, a moment Kidman portrays as a volcanic eruption. Later, they meet in a more upscale hotel suite where Romy notes that Samuel “senses things in people; what they need.” But are they falling into lust, or something deeper?

“I’m not like other women; I’m not normal,” Romy confides to her bewildered husband. While she meticulously constructs her public persona with cold plunges and Botox, she sneaks away to see Samuel, increasingly raising the stakes. His threats to expose her—showing up at her country home and warning he could “make one call” to ruin her—push Romy to the brink. But for her, this is exhilarating. Why? Early hints about her unconventional upbringing suggest a connection between control and freedom.

Romy is also a devoted mother who manages family breakfasts and offers nonjudgmental support to her lesbian daughter (Esther McGregor) as she strays from her girlfriend. The film skillfully balances Romy’s domestic life and her duplicity; the contradictions and compartmentalizations are tantalizing.

Reijn, the Belgian actress (Black Book) turned filmmaker, has created an absorbing psychosexual study. Although it has been marketed as an erotic thriller (Reijn acknowledges a debt to the hyper-sexualized genre of the ’80s and ’90s), it’s after something more mysterious; cerebral, even. In this “thriller,” the danger lies within, where losing control equals liberation.

A standout scene finds Romy slipping away in the middle of the night to a hedonistic downtown rave, the techno beat thumping as she folds into a sweaty young crowd; the filmmaking is dynamic and thrilling, and Kidman convincingly conveys that Romy’s desire has eclipses all reason. And while the plot may flirt with the notions of erotic self-actualization typically found in a paperback romance, Kidman’s performance elevates it into something richer. Watching Romy’s mind race, like a motor shifting into overdrive, is exhilarating, resembling a one-woman cat-and-mouse game between her body and mind.

But there’s more, still, and Romy’s interactions with young assistant Esme (Sophie Wilde) have an interesting, cross-generational connection. Late in the film, eager for long-overdue career advancement, Esme confronts her boss regarding role models and what successful modern women owe one another. “You’re confusing ambition with morality; they are very different,” Romy cautions her protégé. Such insights make a supporting character into a commentary the accountability that must accompany ambition.

While Dickinson brings a devilish charisma to Samuel, he also projects an instability that makes him a bit of an enigma. In one improvised scene, he dances seductively to George Michael’s Father Figure, suggesting something deeper going on than physical release, but since Reijn keeps his true desires hazy his intentions feel more steam than strategy.

No surprise that Ibsen’s Hedda Gabler is referenced, hinting that the story might be headed for a dark conclusion. Yet Reijn instead opts for enlightenment and perhaps even advocates for the saving of a marriage, smartly sidestepping movie convention in a scene between Romy’s husband and lover. Instead of delivering cliche retribution (a la Adrian Lyne’s Unfaithful), she offers a generational debate. While Jacob (beautifully played by Banderas) rationalizes the affair as female masochism, Samuel challenges this view as antiquated, suggesting a distinctly modern perspective.

Kidman embraces Reijn’s sex-positive take on a woman finding, and accepting, herself as a whole human. Delivering one of her most daring performances, I was reminded of the boldness Kathleen Turner exuded in Ken Russell’s 1984 smut epic Crimes of Passion. As Romy, Kidman’s every uninhibited gesture and glance is infused with meaning, digging into what might happen when a woman defies expectations and roles. Hers is the best performance by an actress in an American film this year.

4 stars