Robert Eggers’ Nosferatu is a masterclass in building movie atmosphere from one of contemporary American cinema’s most distinctive young auteurs. With just four films, Eggers has carved out a signature as an exacting writer-director with a personal stamp, blending meticulous attention to folklore and myth with resolutely offbeat storytelling. As his budgets and studio collaborations have grown, his voice has stood firm—crafting films that feel unique, always cinematic yet defiantly uncommercial. On paper, his movies sound as though they might be crowd pleasers, but in execution, they are artily singular.

While The Witch cast a supernatural puritan spell to launch both Robert Eggers’ career and that of its young star Anya Taylor-Joy, his follow-up, the claustrophobic The Lighthouse, was a stylized, two-man power struggle between Willem Dafoe and Robert Pattinson. Then came the mystical The Northman, where Alexander Skarsgård’s blood-and-mud-drenched 10th century Viking sparred with savage foes and a fiercely Oedipal mom, played by Nicole Kidman. Each of these pictures was immersive and historically rich—but also idiosyncratic, more arty than entertainment.

Nosferatu is no exception, steeped in detail-rich artistry and frame-for-frame the best looking and sounding American film of 2024. Eggers take on the classic vampire tale—first brought to life 102 years ago in F.W. Murnau’s silent, German expressionist landmark and resurrected in Werner Herzog’s haunting 1979 version—is an ambitious adaptation that fuses elements from both its predecessors but has a powerful, diabolically calibrated sense of creeping dread. While it lacks the novelty of Murnau’s original and melancholy of the villain—or the unforgettable Klaus Kinski factor—of Herzog’s remake, Eggers’ elaborate Nosferatu is a frightening, richly artistic object of art, loaded with plenty of gothic reverence and dark beauty. The extent to which audiences take to this new version will depend upon their willingness to patiently accompany Eggers into his seductively immersive world, more than be seduced by its villain.

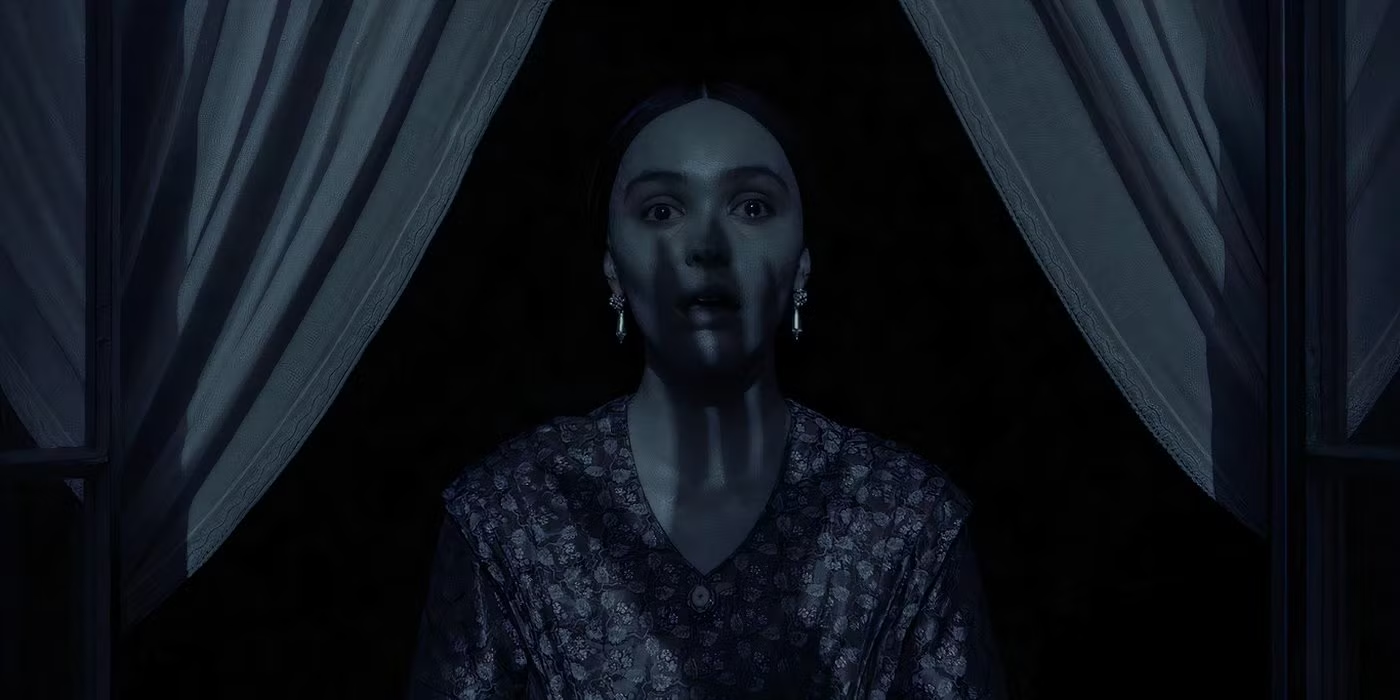

Eggars opens in 1838 Germany, in the foggy, fictional seaside village of Wisborg, where ambitious real estate agent Thomas Hutter (Nicolas Hoult) is eager to prove himself. His newlywed bliss with Ellen (Lily-Rose Depp) hides her dark secret: chilling visions of an otherworldly figure foretelling their future union in a mesmerizing early sequence. When Thomas travels to Romania’s remote Carpathian Mountains to meet a mysterious new client interested in purchasing a decaying Wisborg mansion, one Count Orlok (Bill Skarsgård), the extended section is simply astonishing in visual and aural invention. Beginning at a mountain inn frequented by superstitious gypsies (Eggers’ fascination with ancient, anthropological folklore on full display) and followed by an all-timer sequence involving a tunnel-like, darkened cathedral of trees and the arrival of a ghostly coach deep within the snowy wood, this is lovingly made, eye-popping movie artistry. Ellen, back in Wisborg and increasingly distressed, senses the sinister—and sexual—force awakening.

And awaken it does. When Thomas arrives in Transylvania, he meets the mysterious, frightening Count Orlok, who claims to be interested in purchasing property in Wisborg. But this is merely a ruse to lure the eager agent to his eerie abode—filmed, coincidentally (Eggers was unaware), at the same Czech location Herzog used: Pernštejn Castle. While Thomas is distracted, the vampire sets his sights on Ellen, slipping into her nightmares. “He is coming!” she cries, in gyrations of possession, as does his deranged, rodent-eating servant Herr Knock (Simon McBurney, pulling out the stops).

Meanwhile, Orlok embarks on a chilling seafaring voyage (complete with a plague-carrying infestation of rats) to make their long-awaited communion—sexual, spiritual, bodily—a reality, with plans to spread his vampiric reign across Europe (or something like that). As this reunion draws near the terrific Depp, in a hypnotic performance, convulses and writhes in emotional torture and physical heat, to the confusion of the couple’s best friends (Emma Corrin, Aaron Taylor-Johnson) both unwittingly in danger.

But what about its villain? Is he frightening? The film shrewdly withholds its creepy count, building tension before the full reveal. Departing from the pale, bald, fanged menace of Max Schreck and Klaus Kinski, this menacing Orlok is all grimy decay—grizzled and bedraggled, with a booming, from-the-depths voice, willowy and imposing stature and an almost spectral quality; he’s largely darkened and terrifically terrifying (Hoult, drenched in clammy fear, trembles in Orlok’s presence). While The Northman capitalized on Alexander Skarsgård’s physical prowess and leading-man charisma, brother Bill—known for his turns in It and this year’s unnecessary The Crow—is wholly unrecognizable here. His deliberate obfuscation intensifies Orlok’s threat, Skarsgård embodying an unsettling sense of wickedness; wait until you hear his alveolar trill and rolling, menacing enunciation.

What else to do but contact a fearless vampire killer? In a role reminiscent of Van Helsing from Bram Stoker’s Dracula, Willem Dafoe steps in as Allbin Eberhart Von Franz, an outcast academic turned alchemy and occult expert (because why not?) who surmises that pure evil in the form of “Nosferatu” has cast a shadow over Wisborg, allowing Eggers to indulge in a debate about science (a real plague in the streets) and an bedeviled, supernatural doom in concert in the “modern” world. Dafoe’s arrival injects the film—at times prone to measured pace—with an accessible jolt of energy amidst the film’s heavy aesthetic focus, which can feel slightly precious, or insular for such a straightforward story. While the superbly crafted sets, swirling fog, evocative compositions and chiaroscuro-esque lighting are brilliantly effective at world building (the film deserves to be Oscar-nominated in all technical categories this year), Dafoe really gets the, um, blood pumping, spouting lines like “I’ve seen things in this world that would cause Isaac Newton to crawl back into his mother’s womb!” as joyous asides.

The supporting cast adds emotional texture and increases tension: Taylor-Johnson, in perhaps his best dramatic performance, delivers believable anguish, and, as ever, Emma Corrin brings an intensity suggesting she’d have made a terrific Ellen. Special mention goes to the climactic reunion between Orlok and Ellen, evil and its innocence to be consumed, gorgeously rendered by Eggers and cinematographer Jarin Blaschke and acted by Skarsgård with such beauty and terror it becomes moving in its horrors. This climax is of such sophistication it reminds you that once upon a time American filmmakers achieved art with a toolbox of camera, sound and light. As Orlok advances toward Ellen’s bedchamber, the shadow of his spindly hand stretches and creeps across the moonlit home, flowing up the stairs and spilling over the walls until it reaches its final destination. This is masterful visual storytelling in a film on a level no other American filmmaker this year attempted.

Viewers accustomed to the cheap shocks of modern horror films might quibble with the picture’s pacing. But Eggers isn’t here to dole out easy scares—he’s playing the long game, and Nosferatu is gothic horror as high art craft. Like all of Eggers canon it is studied and methodical, but those willing to embrace its chilling ambiance will find considerable soul within its shadows.

4 stars