You have to hand it to Luca Guadagnino, who this year delivered a one-two punch in the sensual pro-tennis roundelay Challengers and now the equally sexy, dreamlike Queer, his new adaptation of William S. Burroughs’ partially autobiographical 1985 novel (first written in 1952) of a passion pursuit circa 1950 Mexico City. With this combo—radically opposed in style and intent—Guadagnino has demonstrated fierce commercial and serious cinema bona fides as a populist audience pleaser and niche art-film auteur at the top of his game.

In a movie evocative of both era and attitude in its counterculture, Beat Generation meditation on outsider loneliness and obsession, Queer stars an astonishing Daniel Craig as an aging, opiate-addled American expat and writer hypnotized by a beautiful youth and elusive notions of transcendence amidst the tangled jungles of South America. Guadagnino reunites here with Challengers screenwriter Justin Kuritzkes and frequent cinematographer Sayombhu Mukdeeprom to push their collective artistry into new and daring terrain.

Picture opens with Craig’s William Lee (a Burroughs surrogate) drifting through post-war Mexico City, nights spent cruising its lively streets and his days in its smoky watering holes, his literary ambitions overshadowed by a hedonistic love affair with heroin and his homosexual exploits—both of which have made him an exile from his homeland.

Lee’s daily routine includes shooting up, sauntering the streets in his crisp white suit and killing time with flamboyant buddy Joe (Jason Schwartzman), a comic fob prone to hooking up with ne’er do well boys on the take. There’s an erudite finery about Lee, a suave man of letters who’s been around the block quite a bit but is always wiling to take another turn for a handsome stranger, including a sexy pick-up played by musician Omar Apollo.

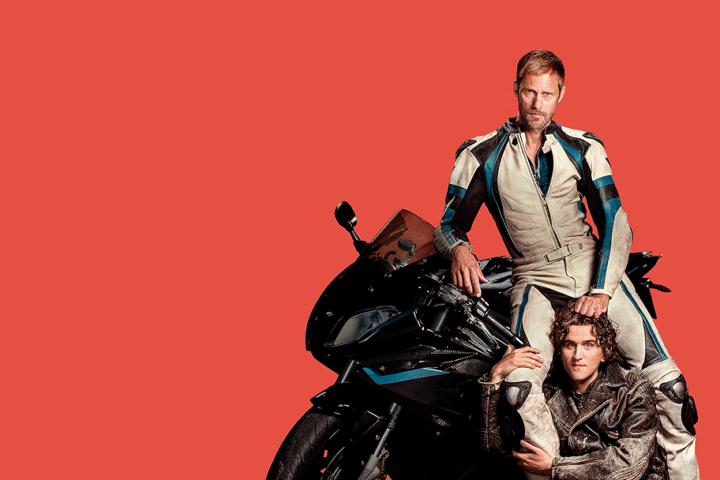

Lee’s world tilts with the arrival of handsome Eugene Allerton, a discharged U.S. Navy enigma played with quiet magnetism by Drew Starkey. Lee is instantly captivated, and their relationship unfolds as a push-pull dynamic: an older man yearning for a younger, ambiguous lover. Eugene, who hasn’t defined himself, oscillates between moments of intimacy with Lee and flirtation with his vampish, maybe-girlfriend Joan (Ronia Ava), keeping Lee (and us) guessing. Is Eugene closeted? Curious? Manipulative?

While the men embark on a sexual relationship, the word “gay” is absent, replaced by a brilliant exchange during which Lee frames his “queer” desires as a familial, almost genetic predisposition, speaking to the character’s self-awareness and denial at a time when the idea of being “out,” even to one’s self, was a radical notion. Eugene’s evasiveness does little to soothe Lee’s loneliness, a void he fills with a needle, and in a stunning extended shot, Craig, alone in his room, drifts into a stupor.

The men’s eventual arrangement—Lee financing a trip to South America in exchange for a twice-weekly sexual liaison—pushes them into uncharted waters. Leaving behind Mexico City for the lushness of the untamed South American jungle, the story takes on mystical dimensions as they pursue “yage,” a potent, plant-derived drug (ayahuasca) that Lee believes will enable telepathic communication with Eugene. Still, Eugene’s motivations remain intriguingly opaque—his intentions oscillate between opportunism and moments of genuine affection. Special mention goes to the frank scenes of physical intimacy between Craig and Starkey—the most explicit ever between two men in a mainstream film, and beyond other boundary-pushing gay love stories like Brokeback Mountain, Guadagnino’s own Call Me by Your Name and last year’s All of Us Strangers.

Scenes of underwater swimming, beachside cavorting and the struggles of Lee’s addiction suggest a developing bond, and one with a delicate ambiguity. One crisis moment, as they share a cramped bed, ranks as affecting as any in recent memory. This section marks a tonal shift in Lee’s drug-induced sickness, the men’s sexual crescendo and, by its final stretches, a hallucinogenic merger both gorgeously photographed and choreographed.

In this closing act, Lesley Manville delivers a standout supporting turn as an American expat in the Ecuadorian jungle—a doctor and medicine woman whose hut, guarded by a venomous snake, is both sanctuary and laboratory. Sharing her home with a sloth and her Ecuadorian partner (played by Argentine filmmaker Lisandro Alonso), she becomes a catalyst for the men’s ever-elusive soul connection. Manville’s enjoyable performance is large in the extreme, but her closing exchange with Starkey—a quiet observation on his condition—is one of the films’s best.

Craig, newly liberated in his post-Bond era (though he’s played gay before in 1998’s Love is the Devil and the Knives Out pictures), delivers a masterful portrait of romantic longing, infusing Lee’s pursuit of Eugene with both humor and heartbreak. The star’s performative bravado—grand gestures and exaggerated charm to impress the younger man—makes Lee both endearing and desperate. Beneath the theatricality, Craig suggests a melancholy yearning for connection, always just out of reach. Their bond, part sexual friendship, part emotional labyrinth, is layered with unspoken currents. Eugene remains a puzzle, and one compares to baked Alaska dessert: hot on the surface, but cold at the core.

Tech credits are superb across the board, and the film’s vision of Mexico City, mostly constructed on Rome’s iconic Cinecittà Studios, has a dreamy, almost unreal quality, one of romantic illusion. The sets, combined with striking digital backdrops, give the city’s streets, bars and alleys an otherworldly quality, and one of tactile immediacy where impromptu cockfights and unexpected sexual encounters lurk around every corner. This stylization evokes vintage movie soundstage shooting but also creates a sense of displacement, as though Guadagnino’s vision of the city exists more in Craig’s psyche than in reality. It’s a choice that, at least for me, recalls the artifice and allure of Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s 1982 queer opus Querelle. Throughout, Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross provide appropriately offbeat soundscapes and a sparsely used, tender love theme (both elements merge in the final sequence). While their Challengers score reveled in retro synth energy, their work here shifts toward the meditative.

In Queer, Guadagnino has crafted a meditation on thwarted passion, transformed from tactile physicality into symbolic abstraction and reverberating across decades. The result is a challenging film that stays with you, and the never-better Craig is a superb guide through love, loss and the transcendent spaces between.

4 stars