Someone once observed that there is nothing in the world worse than going nowhere in life while no one seems to care. In the inspiring new picture Hard Miles (Blue Fox Entertainment, April 19), the true story of Colorado social worker turned bicycling coach and at-risk youth mentor Greg Townsend, Matthew Modine stars in richly conceived role as the troubled teens’ advisor, motivator and the one person who took a chance on them. That chance meant a long-distance cycling trip fraught with high risk-reward potential for the young men in crisis.

Townsend, himself once an unsettled young man, offers the adolescents a shot at hard won redemption in writer-director R.J. Daniel Hanna’s stirring consideration of second chances, support and compassion. While on its face Hanna’s Hard Miles may suggest a “sports” film, the filmmaker and co-writer/producer Christian Sander have crafted a moving road movie about personal transformation both intimate and writ large across the American southwest, its landscapes an open air catalyst informing the arduous trek from Colorado’s Ridge View Academy correctional school to the vastness of the Grand Canyon.

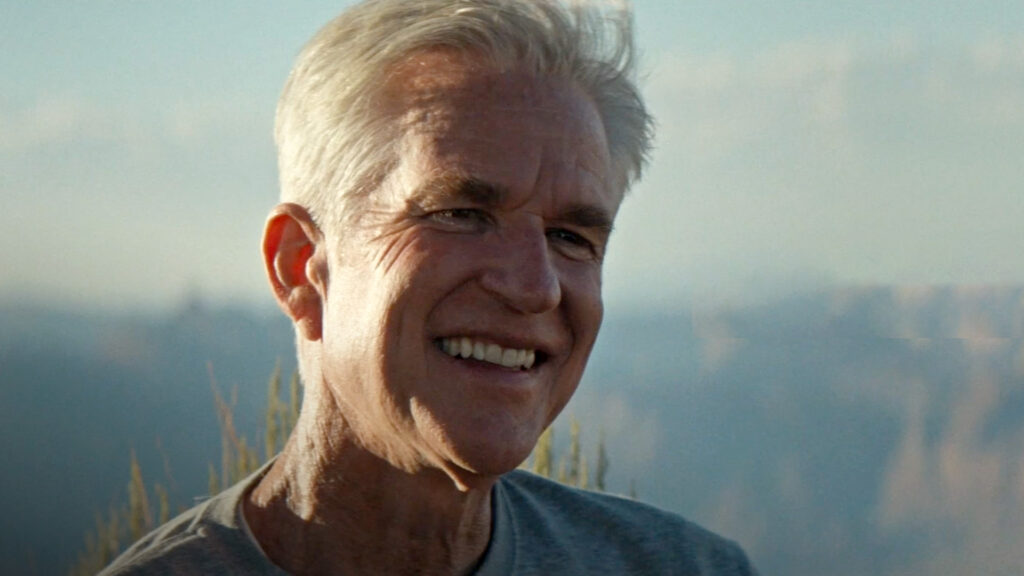

I recently caught up with Hanna, Sander and star Matthew Modine to chat about the making of their crowd-pleasing new picture in what became a far-ranging discussion on its production, talented cast, observations on what makes a good picture and Modine’s expansive, eloquent thoughts on movie acting, including its cultural imprint and impact. The actor, with an impressive forty-year career in film, television and theater, offered both inside acting perspectives on the nuts and bolts of scene-craft as well as a pointed philosophy on the relationship between humanity and the art of acting.

How did you come to Greg Townsend’s story?

Christian Sander: I was aware of Greg Townsend and what he was doing at the program. There had been a few articles written about him and what he had done with the kids. I thought it could be a great sports movie, but I wanted to go check it out and see what it was like. I reached out a few times and he was not initially receptive, but I was able to connect with his wife, Maureen Townsend, who was receptive, and she became my secret ally! So, I wrote Greg a letter.

He just wasn’t initially interested in directionally what the movie was going to be?

R.J. Daniel Hanna: He was not a Hollywood guy. People who have found their calling sometimes are most interested in that, and he was working with young men, and I think he thought this would be a distraction. But he came around to the idea that this could be something that would inspire someone to get into youth services and amplify what he was doing.

Hard Miles is a road movie. It is a sports movie. It is a movie that is going to make anyone who sees it feel good. And it is one that has an incredibly likable character in it. There is probably a tendency in sports movies to create easily identifiable types. But all of the actors in this movie bring something distinctive to their roles; each had some point of interest. If you made a movie about any one of those kids, it would have interest. It would be great to hear a little bit about why you chose those actors, particularly Jahking Guillory.

RJDH: Sure. There were actors competing for each role who came in and auditioned all together, and we were sort of interchanging them. It really was all about the direction we wanted to go because each actor brought something special to it. Jahking is a born leader. He exudes that energy. He’s got a very strong head on his shoulders and brought that to the role…

CS: …which was exactly what we wanted for Woolbright. We had this idea that he would be like Ferris Bueller, but with the potential to go the wrong way. And I think Jahking brought that leadership. He had that power and energy.

RJDH: Yes, he would be someone who would go his own way. People would want to follow him. It was like the conflicts that Greg has in getting the kids on his side so that they will go on the journey with him. Jahking is like the voice going against the stream; he has a lot in him.

Did you pair him with Matthew prior?

RJDH: No. We had our table read with Jahking and Matthew, and we had pretty much made the decision. It worked great.

How about Cynthia Kaye McWilliams? She’s also terrific here..

RJDH: She is terrific. In her reel she had all of the qualities that we needed. We could tell that she would be hard and real and funny. And that is tough line with a lot of the actors because they must be funny and then just turn it right to the edge of what might be too much.

For example, when she’s pumping the air.

CS: Yes! Her instincts were spot on. Where she should go first was like, ‘Yes!’

RJDH: Yes, It was all there. They all registered so well because every actor had reserves of what the characters needed. They had it and they were bringing it all the time.

Did you guys do the entire 762-mile cycling trip?

CS:I have ridden three thousand miles this year, but I think the boys probably rode about ten miles per day. Those were ten hot, climbing miles but not as much as they did in real life.

RJDH: There was a version of this movie we discussed earlier that would have been more of a literal ‘on the road’ movie. But in order to really do good work we needed to land and take over an area for a week, build out from there and get everything we needed. We did do a bit more and had some pickups and shooting along the way on the road to get bits and pieces.

It’s believable that the whole trip was done in the movie. I enjoyed seeing those places I had been to before, like Monument Valley and Independence Pass, which is the scariest drive I’ve ever done, and of course, Grand Canyon. There’s a travelogue part of the film that’s effective as well. What does this physical world mean in the transformation?

RJDH: Thank you. We had an awesome cinematographer, Mack Fisher, and wanted to take a naturalistic and real approach to it. There were things that we pushed against to keep it grounded, like maybe some of the more sports movie tropes. We wanted to feel the transition from being in a city and overwhelmed by cars and all of this stuff to the trailer park and then actually into nature; to be truly in the middle of nowhere, isolated and feel that creep up as the boys start to feel that suddenly they are in a different place.

I think you can feel that in that scene where they are lying underneath the stars looking at the expanse. And you realize they’re kind of really getting someplace. Matthew, this is a terrific character for you. I can’t imagine anybody not being engaged by him. Greg Townsend gives you a full arc where you are a mentor and a guy who has a vision and a view of what these guys are capable of, which as he explains is more than their rap sheets. Additionally, the character has his own personal health issues as well as the reckoning that happens with his father. It’s a rich character for you. It does transcend what we might think of when we think of a ‘sports movie.’ You must have been attracted to that.

Matthew Modine: Oh, yeah, one hundred percent. It’s not easy to sort of talk about that. You have obviously really looked at the film and understand it and the character. I think it’s important to see this man at this moment in our shared history. We are living in such a binary time where ‘I am right and you are wrong,’ ‘I am smart and you are stupid.’ That way of thinking and being is unrealistic and not sustainable. R.J., it was such a beautiful thing that you said introducing the film, which was that if you are going downhill, you are coasting. Going up a hill demands effort and suffering. I think we have been sliding down a hill as a culture, not just in the United States but all around the world. We have been coasting for a long time with the environmental degradation that is happening throughout the world, with eight billion people on the planet consuming resources at an unsustainable pace. An economic system based on the consumption of goods s a system that is designed to fail. We would need a couple more Earths to consume the resources at the pace that we are going.

And so for a person like Greg Townsend, what he represents is important because he’s reminding us that in order to accomplish something it is going to require effort and discomfort, and the journey that he takes those boys on is uncomfortable and while he can easily appear as a son-of-a-bitch who is unrealistic and pushing the boys too hard, he knows that in order to be able to help them change their lives he’s going to have to do that. It’s like the football or wrestling coach or history teacher that you had in high school that demanded more from you. It was not because they did not care but it was because they knew that when you graduate from high school and college that nobody gets a participation prize, and that in order to survive in the world you were going to have to put in some effort.

If you are going downhill, you are coasting. Going up a hill demands effort and suffering. I think we have been sliding down a hill as a culture, not just in the United States but all around the world.

Matthew Modine

He rejects that binary way of thinking at the beginning of the film when he’s sitting next to the young man whose case is being decided. I think there’s probably a point in the movie where you win the young men over and are able to share compassion and goodness. I found that dynamic in the movie to be clear and strong. The apex of this would be the scene between you and Jahking up on the cliff. Could you talk a bit about the interaction between your characters in that moment?

MM: Yes, I think it was important for Greg to apologize and to realize he was being the unreasonable father that he had grown up with, pushing them and in doing so becoming something he consciously wouldn’t want to be. I don’t think that Greg Townsend would ever want to be like his father, but we are all creatures of the world that we come from. I never met Greg Townsend’s father although I did meet Greg, and I would describe him as a very loving father. I don’t believe that anything he has accomplished through the welding classes or the bike rides would have been possible without a tremendous amount of love. So I think he’s human. He made a mistake in insulting Woolbright, but how wonderful that he could acknowledge that he was human and made mistakes and said things that were ignorant and rude, and owned up to it. That was part of his own personal growth in this story.

One of my longtime college friends, Gabby Sanalitro, is in the film. She plays the nurse that leads you in to see your father.

MM: She was great! Isn’t it funny how someone with a small scene can have a big impact?

Yes. Just the way in that moment she halts what she is saying and there’s a bit of a pause. It’s a nice exchange. On the father-son scene, I think we are waiting for it to arrive. Those are hard to do without making them maudlin. Somehow, perhaps because it’s very simply shot, with the shot of you and then the shot of the actor playing your father, followed by the morning after, it works nicely in its simplicity. How did you set that scene up? Can you rehearse for something with that sort of simplicity?

RJDH: We pretty much never had any rehearsal. We had the one read through and talked about things. Matthew and I talked about that scene a lot. We were concerned- as a writer you are coming at it from different ways and wanting to make sure it was clear. That scene was always overwritten and there were a lot of things happening. We were trying to figure out all the things that needed to be tied up, and would mean that Greg had reached his place of peace with it. How could that be expressed? We went back and forth quite a bit on writing and cutting things away and trimming things down, and even on the day we shot it we trimmed down more. It was all there and coming through, mostly silently really, and so I think the approach was how much we could say and feel without having to say it.

MM: It was one of our first big concerns. With everything that was happening in the story about these boys and the bicycles, I thought if we eliminated this whole dad line it would give us two or three days to enrich and tell the other stories. I wasn’t sure that one was going to have the payoff we hoped it would. So that would have eliminated the brother calling, the hospital scene and dialogue throughout where we are talking about that.

CS: There are two things I think are effective about that scene. If you’ve ever been in the room with someone as they pass on, after it happens you are empty. You have experienced all of the emotions and then for the next day or two it’s just nothing. I think with the lighting effect that you did and in Matthew’s performance afterwards, it captured some of that emptiness; the void that is left. But also, that was Greg’s mountain. You talked about it being a sports movie. And we wanted to do that, but we wanted to subvert some things. In sports movies there is a game that you can win or lose; an external motivator that is a win or loss situation. This does not have that. They are not in a race. It’s an internal conflict and the characters have to climb their own mountains. And moving Greg’s mountain was reconciling with his father and practicing in his own life what he was preaching. He can do it in all these other areas but until he applies it in his own life where it hurts most, I don’t think he gets any credibility with the boys.

Let’s talk a bit about the production. I understand there was a windstorm at one point and a mountain lion that intervened. How long did you shoot for and were you able to stick to the plan?

RJDH: Yeah, we definitely had a tight schedule throughout. It was 23 days…

CS: It was 28 total days but five of them were pickups.

RJDH: Yes, 23 days of real production and then a few days of extras on bikes.

CS: But a lot of the days were long travel days to set because we filmed in so many unique locations. You can’t really green screen these things.

RJDH: We would have to drive two or three hours to locations. We stayed the night in certain places.

For example, going to Monument Valley to get those shots.

RJDH: Yes, that was a pickup along the way. But most of our mountain stuff we would drive a few hours, film the rest of the day and stay overnight. We did meet 60 to 80 mile an hour winds.

CS: We had to shut down the set because it would have been an OSHA violation. And we did have a mountain lion. Across the creek from where we were shooting a lion and a coyote were facing off; they had a tussle and the coyote got away.

Is there any violation when it comes to running out of gas in the middle of a sweltering day?

MM: (laughter) Just ignorance and stupidity, which is not redundant to say! I know better because I grew up in the desert. Whenever you get in the car you check the gas and make sure that you have water. That is basic. On that day, I had three or four hours that I wasn’t needed so I thought I would go get something for the crew, which would be something they could not get out of Navajo territory, which was watermelon.

CS: Matthew had carpooled with some hitchhikers earlier and he had it pay it forward—and then he got it paid back!

MM: Somebody pulled over and gave me a ride back and forth to get gas so I picked up some hitchhikers, to his chagrin, because of insurance rules driving up to Mount Whitney!

Matthew, I grew up in the 1980s so I’m just a little bit younger than you. My good friend, Mike Gallagher, who is the same age as me, and I grew up watching you, and we still watch movies you did at that time. We frequently talk about Birdy and Vision Quest.

MM: Thank you!

They have stood the test of time for us and we’ll probably always watch them. It was a much different era in which you fell into some great roles with great directors and those are forever sorts of things. When you look, for example, at the scene with you and Nicholas Cage at the end of Birdy and the monologue, or the scene in Vision Quest with you and Linda Fiorentino where she kisses you in the diner and the expression that you give her, for a generation of guys like me these are kind of indelible movie images and scenes. Are you aware you made a cultural imprint in that era on a lot of us?

MM: You’re not aware of it at the time that you’re doing it. I’ve made over 100 films now and you never know how successful—or not—one will be. I do know that with every project I go in with the same enthusiasm. I work just as hard on something that is successful as something that is not. And we are all given the same equipment to make a movie. There are cameras, sound equipment, lenses and crew. Everybody comes with great enthusiasm to make a good film. Sometimes it works and sometimes it doesn’t. It’s like a pair of ladies’ stockings. It only takes a snag for them to get ruined. I have not figured out what that is. I do know that this element of producer/director is really crucial as is putting together the right team that is knowledgeable about the project they are trying to make and has some understanding that you’re dealing with a lot of variables.

I sometimes think about acting like cliff diving. It’s not just diving off the cliff and doing a beautiful swan dive. You have to hit deep, dark, cold water. It’s a lot of moving parts and sometimes you hit your head.

Matthew Modine

You are dealing with artists. People think the makeup department or the hair department is not important. That is the first place an actor goes when they come to the set. And if they are in an ornery mood, it is the first person you are deal with. It’s really important. You should never think that hair and makeup are not important departments. Wardrobe is really important. The wardrobe person we had on this one worked her ass off. She was doing the laundry every night. My heart went out to her. She was amazing. Everybody that worked on the film had some understanding of bicycling and what that meant physically to the actors, so that they could be empathetic to the fact that we were doing multiple takes. If you did not understand what it was to ride a bicycle you would not have had any empathy and thought, ‘What a bunch of whiny babies who are tired of riding bicycles.’ It’s only a quarter of a mile or a half mile with the shot going back and forth, but if you do that four or five times and you do three or four setups a day, you start putting in a lot of miles. And then you are also thinking mentally about what you have to say and where you are in the story. Many elements go into it

But of course, the most important person on the film set is the director because he, she or they are the people that have to conduct, like a musical conductor, all of those elements and pull all those artists together to create a symphony and a beautiful piece of music. And it’s not an easy job. I’ve worked with some directors that are not so good and somehow pulled it off. But it is much better when you are working with somebody that you trust. This is the second time I’ve worked with R.J. I like his sensibilities. I liked being able to say that we should cut the dad material out and that he had a vision about why the dad was really important. And again, this is an important thing because we are living in a time where ‘I’m smart, you’re stupid,’ ‘I’m right, you’re wrong,’ and if I was an asshole actor I could have said ‘Look, I’m not going to do the movie if you don’t cut this out.’ There are actors that do that and I think that is really stupid. I’m not always right!

I sometimes think about acting like cliff diving. If you’ve ever been to Acapulco and seen somebody dive off a cliff or have seen video of it, you climb up to the top of that cliff and it’s not about just diving off and doing a beautiful swan dive, but it is also about timing. You must wait for a swell to come in and hit the rocks, and then as that swell is going out another one is coming in. The moment when the swell leaving meets the swell arriving is when you have to hit the water. So, it’s not just diving off the cliff and doing a beautiful swan dive. You have to hit deep, dark, cold water so that you don’t bang your head on the rocks and kill yourself. It’s a lot of moving parts and sometimes you hit your head.

It would be great to hear the group’s thoughts on this orchestration of elements. I would imagine over the course of the shoot you looked at the dailies and knew what you were getting, but as Matthew just said, you may not have. In terms of orchestrating the whole and keeping it pointing in the right direction and getting it exactly where it needed to go, between the two of you, R.J. and Christian, that was on you guys. What was the kind of overriding philosophy of making quality and not mistakes?

RJDH: Every movie is different and has different needs. You have an idea of what tone can be and should be. Some things come through this screen and some things do not. It is hard to exactly pinpoint why that is. Either you have the feeling of it connecting and coming through and breaking through and you know that is the moment that you need—or not. I think of it as balls in a lottery drawing. The balls are dropping and the number we needed just dropped in this scene. That is the moment of connection. We are trying to get all the little balls to drop so that we have the winning ticket. It feels like in every scene you know what you want to get, and you know if it’s wrong in the sense of a gag reflex, which someone else said, whether it is maudlin or when it goes right up to the line of what could be too small to see, or to this, or to that.

I think a big thing as well is trusting an actor’s process and that an actor might need to go big. This was something I experienced in editing a different movie that I directed. This person went big in this one moment. But if you take out that one big moment what you have is just this great energy that is there under the surface all of the time. So, I think a lot of it is about just trusting the process too. Knowing what you want but just trusting that you’re going to go there on a winding road. Sometimes what you wanted was obvious and what someone else gave you was unexpected and interesting, and maybe you should lean into the thing that was unexpected.

When I teach acting classes to young people today, I don’t ever try to teach them how to be an actor. I’m not sure that is something you can teach. What I know I can do is to help them to be better human beings.

Matthew Modine

Can you think of something on this film that might have been unexpected?

RJDH: This is a very minor thing, but Matthew, do you remember lying on the floor of the office on the first day? I did not picture he was going to stretch like that. But then I realized it was kind of nice because I had him at a very low and vulnerable place very early in the movie. His boss came in and then he had to sort of work his way up from that vulnerable place without making a big thing out of it. Things like that are just a little drop of chaos in your planning that forces you to adapt. This movie was full of that stuff—bikes, deserts, nature. If you embrace the chaos a bit instead of saying that you really wanted something to be framed a very specific way, it gives you a little more flexibility to maybe get something more authentic than perhaps produced and created. It was nice doing that on this movie because we could have gone the other way and tried to make everything like a postcard, which would not have been the messiness we wanted to go for. Sometimes if I find a scene isn’t working it’s because the energy must change. Good actors have an instinct for that too. Mack is a very free flowing DP and I’ve worked with some who are not.

MM: In that scene that he’s talking about, where I’m laying, there is expositional dialogue. You might call it ‘laying pipe.’ It’s information that the audience needs to hear about moving forward. And what you must be careful with is not sounding like you are laying pipe when speaking exposition. So, the best thing that you can do when you are in a scene where you are laying pipe—and generally you are a protagonist in your story, and you don’t want to be the protagonist laying pipe—you surround yourself with character actors like Leslie David Baker, the guy that comes into the room. He nailed it. He’s great.

So, when you have expositional dialogue and you are the protagonist in the story, you don’t want to get caught speaking exposition. For any actors reading this, the best thing to do when you are in that situation is to give yourself a physical activity and find a way to show it. So, what am I doing in that scene? I am on my back, tucking my shirt in, putting my belt on, putting my jacket on and rolling up the mat. I was desperate to hide this dialogue with all that physical activity!

RJDH: I also remember that you were not crazy about wearing the red shirt. On the first day you put the blue jacket on and zipped it up. And then that jacket was on you for almost the rest of the movie!

MM: That was the costumer. When I came in, she asked me if there were any colors I did not like. I told her red and beige. All she had was red, including the jacket and the singlet. I’ve got a lot of red in my genetic background and wearing that color just makes the red come out in my skin, so I look pretty ruddy in the film; plus, all of the sun and the temperature. It is probably the least attractive I have ever felt when I have watched myself in the movies.

Do you watch yourself? Some actors say they never watch their movies.

MM: I’ve seen the film twice. I am really happy with it. I think it’s a really good and important movie, particularly because of this time that we are living in that I talked about before. It weird watching yourself get old. When you mentioned Vision Quest or Birdy or Full Metal Jacket, I gave them magazines that sort of chronicled my career, and I don’t feel any different than the guy that played Louden Swain or Birdy or Private Joker, but I don’t feel that this thing I am existing inside of is me. It is just something that I inhabit. I don’t know what that means but that is how I feel. I am sort of existing inside of this thing. If we never saw ourselves in a reflection how we would receive ourselves? How would you draw a picture of yourself if you never saw yourself?

I think sometimes we as press or film fans take movies to heart and make them part of who we are in our nostalgia as well as acumen, and sometimes the same may not be equally true for the actor. You put it out there and it means perhaps something more for those who see it. Maybe that is the point.

MM: Music does this for me. But that was the most powerful thing when 911 happened. I had been downtown a lot and then something happened and I could not come downtown anymore and hand water bottles out to firemen and emergency workers. One of the older firemen said to go to Jacob Javits (Convention Center), which was where all the FEMA workers were staying. And I said, ‘What am I going to do at Jacob Javits?’ And he said, ‘Just go there. You will find out.’ He knew. He was an old, wise guy; not a mafia wise guy.

I went there, and I was saying hello and shaking hands and some guys had a shift change. Many of them came in from the pile, all covered in white horror, and they stopped and the dust fell off of them. And one said, ‘Private Joker!’ And he came over and gave me a hug and said he couldn’t believe it! And suddenly all of the weight that he had been experiencing and God knows what he had seen and cleaned up and picked up—he left that place and went someplace else. He was able to call home to his family, his wife, his kids and they knew that their father was someplace where somebody was looking out for him. It wasn’t Matthew Modine. It was what Matthew Modine had the absolute honor of participating in, which was being chosen as the guy that played Private Joker in Stanley Kubrick’s Full Metal Jacket or Alan Parker’s Birdie or Harold Becker’s Vision Quest. And it honestly has nothing to do with me. I was a vehicle chosen to present it.

Film has the potential to help us give context to our lives, understand the difficulties that we are living through, see ourselves in others and have others see themselves in you. It really has an extraordinary power.

Matthew Modine

So, what film has the potential to do is to help us give context to our lives, help us understand the difficulties that we are living through, see ourselves in others and have others see themselves in you. It really has an extraordinary power to change the course of human history. I say that without any exaggeration and with humility. Because how amazing to be part of a profession- and I think that’s why we want to be a part of it and work inside of it is that we, ourselves, have at some point been influenced and changed by those experiences.

I know for me it was when I saw Little Big Man at my father’s drive in in Utah. I was going to school with the Navajo and suddenly—after all of the cowboy movies I had seen up to that point, which had shown white settlers being attacked by savage Indians—the camera pivoted and we were watching a movie about indigenous people being attacked by white savage cavalry, killing them, their ponies and their children. It altered my perspective. And the grandfather in the movie, Chief Dan George, he called themselves human beings. And from that point on all I wanted to be in my life was a human being.

When I teach acting classes to young people today, I don’t ever try to teach them how to be an actor. I’m not sure that is something you can teach. What I know I can do is to help them to be better human beings. We don’t need more actors, we need more people that understand what it means to be a human being, to be kind and forgiving and loving and have empathy and show forgiveness to other people.

It seems hard to project that on film.

MM: Well, you have to live it. You have to walk the talk.

It seems easy to convey being a bad person or a villain or whatever extreme of some kind of behavior. But just to convey the idea of being a good person seems difficult. So for example, in Vision Quest, the way you deal with the man who is your colleague at work. There’s that wonderful, lengthy scene. There’s something inherently nice conveyed.

MM: That’s why all the really good directors will tell you 90% of making the movie is casting the right actor.

It seems like it’s missing today. There’s hyper confidence in young actors. There’s maybe an over savvy that makes them less vulnerable, less accessible in some way. It’s not necessarily like it was a couple of decades ago.

CS: I think they also are missing a lived experience. If you are eighteen years old how much have you really lived yet? Storytelling is this great technology that we have to put yourself in someone else’s shoes and feel empathy and think about somebody other than yourself. We’re the only creatures on Earth that communicate and learn in this way. I think it’s the Hemingway school of writing. You can’t really sit down to write if you haven’t lived.

RJDH: I think with the idea of young people today, or however you want to phrase it, it is kind of the opposite. They haven’t really lived yet but they are so inundated with imagery and media and perspectives on things. It is not lived experience. It is like an illusion of it. So, there’s a lack of earnestness and openness in that regard.

MM: They have grown up in front of the cameras too. Also, everything is being recorded.

RJDH: There was something a professor of mine said in film school that was good, which is that you are all so afraid of being cheesy. That’s the biggest fear. But if you are cheesy, you are just going too far down one direction. You just have to reel it back in a little bit. It would be much worse to be so afraid of going for it that everything becomes very cold and detached. Hopefully things go in cycles. Right now, I think everyone is so afraid of being viewed as naive or earnest about something that they are not open. You have to be open.

MM: Let’s say you’re the producer and the casting director and have got this list of contemporary actors. Nicolas Cage? Do you want to cast him? Would you cast him to play Greg?

RJDH: He could do something interesting.

MM: Matthew Broderick?

RJDH: I don’t know.

I just saw Nicolas Cage in his new film Dream Scenario. I think he’s a magical actor. He has this toolkit that allows him to do comedy and tragedy almost simultaneously in a way that no one else seems to do. I think that is sometimes forgotten.

RJDH: I love him in Adaptation. He is great. Absolutely. You have to accept and embrace an actor’s interpretation when they are someone of that caliber. I don’t think we see so much variance today between actors where you are going to get a big swing.

MM: There’s the ‘Nicolas Cage moment.’ I think there’s a name for it. What scene in Hard Miles would have the rage? When would it come?

RJDH: Maybe the father scene. It would be an entirely different thing. A different perspective.

Or the scene where the phone call comes about the lack of funding.

MM: This is an interesting exercise because I’ve done three movies with Abel Ferrara, and one of them is called The Blackout. I wanted him to change the text (in one scene). I was talking to Beatrice Dalle, and I say to her, ‘Did you cut the baby out of your stomach? Did you have an abortion? Did you cut that fucking baby out of your stomach? I ought to take a knife and cut that baby out myself!’ I said ‘Abel, I can’t say that.’ Abel can say it. There’s something about him saying it that there is no threat if he says it; he’s not literally saying it. But having me say it? There is something about my chemical makeup and what I am as a human being that people are going to think, ‘What the fuck happened?’ They are going to take it literally. Abel said, ‘No, they won’t. They know that you’re just pissed off.’ I said, ‘They are going to think I’m trying to kill her.’ And it’s true, because I say something with a certain kind of conviction. So, when you cast an actor there is a conviction that comes in a way that they are going to interpret it that is very different. Hard Miles would be a very different movie with Nic Cage.

This reminds me of when Tarantino made Kill Bill: Volume 2, and Warren Beatty who was attached to it…

MM: Which part?

Bill. He was going to play Bill.

MM: Was that Carradine?

Yes it went to David Carradine. Tarantino kept telling Warren Beatty he wanted him to play it like David Carradine would. It came to a certain point where Warren Beatty said, ‘Why don’t you just hire him. I’ll leave and you can hire him.’ So he did. But what you said is interesting—when you hire the actor you accept they’re going to bring their interpretation.

MM: I would quit if somebody said that. In fact, on Stranger Things, the Duffer brothers said that my character was kind of like the Peter Coyote character in E.T. They called him ‘Keys’ in E.T. They would always cut to his keys. They said this character was kind of like that. The way he was written, with a couple days beard, jeans and flannel shirt… it took everything in my power- they said, ‘Look, wear a suit like Cary Grant in North by Northwest.’ If I fall, when I get up it’s going to be clean and tidy. I’m going to be so clean shaven that I want the audience to smell my after shave.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.