Sofia Coppola’s Priscilla, about the domestic entrapment felt by a young Priscilla Beaulieu (and later the married Priscilla Presley) during her fourteen formative years with Elvis, offers few new insights in attempting to illuminate a complex and very public relationship. As written by producer-director Coppola, what we learn in the film is little beyond the expected—that young Priscilla was a kept wife, frequently dominated and disregarded by a too famous older husband; a woman of her time without means, agency or her own identity. As the movie, based on Priscilla Presley’s 1985 memoir Elvis and Me tells it, Elvis insisted on all of the above. That is the extent of the film’s scope. If the picture were not about the Presleys’ famous celebrity marriage, a part of popular culture history, its familiar domestic dynamics would be a head scratcher for a feature film.

We first meet fourteen-year-old Priscilla (Caille Spaeny) in 1959 West Germany, where her military father (Ari Cohen) is stationed. While her parents, including her mother (Dagmara Dominczyk), are cautious about their barely teen daughter growing close to twenty-four-year-old superstar and army recruit Elvis Presley (Jacob Elordi), who has taken an interest in their daughter after Priscilla attends a party at his rented home in Bad Nauheim, Germany, the pair quickly fall into an almost storybook whirlwind romance. So far, so good, and Coppola does a lovely job infusing their budding courtship with genuine romantic longing, too smart to engage in modern “right or wrong” critique of the age disparity, thankfully—and chastely—presented without judgement.

Young Priscilla is understandably distracted from her studies, and despite her parents’ protestations she eventually relocates to Graceland, after which the troubles begin. Returning home from his military stint and now a hot Hollywood property, Elvis leaves Priscilla alone at Graceland for weeks on end, loneliness replacing chivalry. Meanwhile, salacious movie magazines detail starlet infidelities. Truth or fiction? Suspicious minds, indeed.

This dynamic—Elvis returns home, Priscilla confronts him, he shuts her out of his career and possibly illicit affairs—goes on for most of the picture. Expectedly and along the way there is marriage and the birth of Lisa Marie. The picture connects these well known dots in a rudimentary, low-key way, adding nothing we don’t already know or could reasonably surmise about the family dynamic. One has to believe Priscilla’s life was more interesting than the cursory domestic outline onscreen.

Despite Priscilla Presley’s executive producing credit, Coppola was apparently unable to secure the rights to Elvis’ music catalogue and the film suffers significantly from lack of cultural context. Some will shout that “it’s from Priscilla’s perspective” so no matter, but the lack of Elvis material significantly robs the film of both the Elvis mythology and his larger than life dimensions, critical in its tale of a fourteen-year-old girl so smitten with an international celebrity that she is willing to grow up very fast to be with him, and endure years of apparent marital subjugation. We need to see and feel that pull, and without Elvis’ musicality—even as background—the film feels inert.

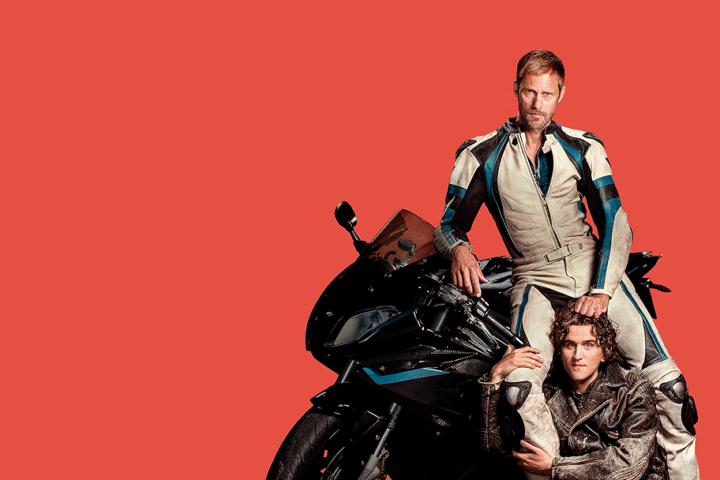

Coppola, a deft and appealingly unpredictable filmmaker (her best may still be her 2003 debut Lost in Translation), approaches the challenge of having no access to Elvis’ catalog by effectively deploying other music of the time (including a nice use of Tommy James and the Shondell’s Crimson and Clover), clever period production design and impeccable costumes. Yet somehow we never fully believe Spaeny and Elordi as Priscilla and Elvis; there is something askew here, an at-times sense of almost dress-up artifice that conveys a stunt approximation of a larger than life cultural touchstone duo.

Spaeny, a capable actress and fetching presence, does what she can with a role that requires the same few notes over and over—boredom at Graceland, suspicion over Hollywood costars, pleading not to be abandoned. But the true accomplishment of her performance is revealed in the film’s concluding 1970s passages, during which we recognize a genuine onscreen evolution from naïveté to sophistication.

But handsome, breakout leading man Elordi is slightly miscast (his burn through charisma far more effective in the upcoming Saltburn) as Elvis, lacking in resemblance, too tall and lanky and, in this picture at least, without the opportunity to deliver the king’s star magnetism. It does not help that Coppola has written a version of Elvis that is little more than by-the-numbers history record—running off to make movies, Nancy Sinatra and Ann-Margret rumors, devout Christianity, et al. However, despite the limits of the material Elordi impressively masters Elvis’ speaking voice in tone, structure and patterns; the vocal interpretation is seamlessly convincing and the genuine article, and great to listen to in every line.

The cinematography, by Coppola go-to Philippe Le Sourd (The Beguiled, On the Rocks), appears consistently and fussily underexposed, its interiors strangely and inexplicably dark from the Beaulieu family home to Elvis’ stationed apartment to Graceland; I struggled to make out faces in some scenes during its first half and frame corners are constantly shadowy creating a sense of detachment from what is happening onscreen. I am certain projection bulb life was not an issue as Priscilla was the second of two consecutive screenings in the same multiplex auditorium that exhibited no prior issues.

Neither hagiography or drama, Priscilla struggles for a reason to be. Perhaps the perspective shift from last year’s Baz Luhrmann fantasia Elvis and the inner marital dynamics were the goal. Unfortunately and despite the fame at its core, those dynamics do not make for a compelling enough biopic, and this version of Priscilla coming into her own from a fairy tale gone wrong registers little impact.

2 stars