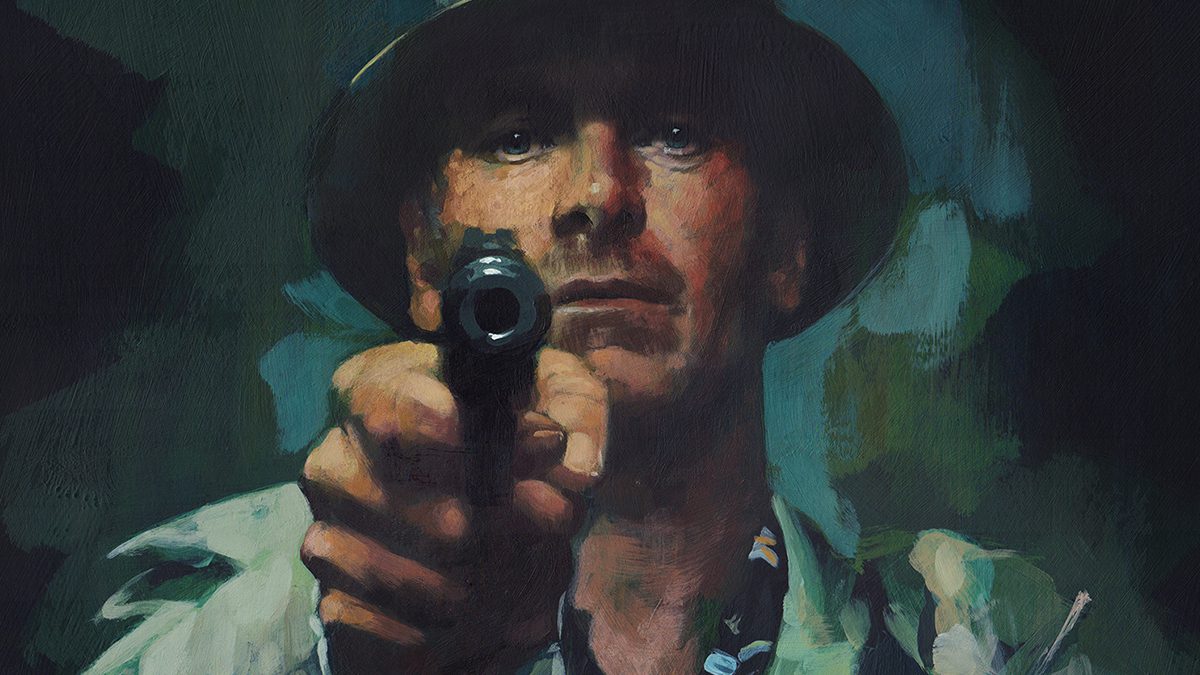

Stick to the plan. Anticipate, don’t improvise. Trust no one: Words to live by and a mantra for a best in the business assassin whose carefully constructed world crashes down after a botched hit in David Fincher’s superbly constructed thriller The Killer. Played with chilling exactitude by Michael Fassbender, ice water coursing through his veins, this titular killer is a study in solitude and bloody retribution. It is also one of the year’s best directed pictures, a handsomely made aria of melancholy and brutality served cold and with impeccable technique.

An immensely propulsive piece of elevated pulp scripted by Andrew Kevin Walker (Seven), Fincher opens his picture with an overture of measured observation as we meet an unnamed executioner perched atop a Parisian high rise WeWork space (for him, just another day at the office) in alternating throes of boredom and contemplation, monologuing in voice over—life, his place in the universe’s pecking order, notions of birth and death as simultaneous and equally necessary—as he watches and waits to kill, all accompanied by the poppy gloom of Morrissey and The Smiths, heavily featured on the soundtrack (and through his Airpods). But when will his intended target arrive at the elegant hotel penthouse across the way? Hours turn to days while he patiently bides time, firearm at the ready, a Lee Harvey Oswald in waiting, finger on the trigger. And then, for the first time in history—he misses his target.

He knows what this means before we do—that a trio of equally trained killers have been dispatched to take him out, their first stop the Dominican Republic home he shares with girlfriend Magdala (Sophie Charlotte), hospitalized by the cruel thugs who get there first. But who exactly is responsible? One of the picture’s best sequences leads to the Manhattan office of his imperious boss (Charles Parnell) and, in a bloody roundabout, the identities and whereabouts of his pursuers. Credit actress Kerry O’Malley, terrific, as the terrified executive assistant who holds the key but insists on an unexpected request in exchange.

The picture’s second half is an expert, elevated Death Wish payback schematic that keeps topping itself with locale changes—New York, New Orleans, Florida and finally Chicago—globetrotting fake identities (including the sublimely funny “Lou Grant”), feverishly ballsy action (good fun made of Floridian denizens) and welcomely unexpected cameos that make for a very entertaining final act. Chief among them are an uber-civilized Tilda Swinton as a platinumed, classy chi chi killer who makes the act of drinking a whiskey shot a veritable last supper of refined fatalism, and an appropriately unnerved Arliss Howard as the top-of-the-chain currency magnate and firing squad financier who gets the scare of his life, a scene of threatening, slow-burn intimidation.

The Killer feels like a return to sophisticated adult thrillers made with muscular style, economically and efficiently no nonsense and courtesy of Walker, a finely observed rumination on mortality and the currency of power—who has it who does not. It is also a flawless union between writer, director and star, Fassbender’s flinty, (almost) break no sweat under pressure performance a dazzling enigma of steely command.

Fincher, the premiere visual stylist in American commercial film, crafts an aura of expertly lensed visual intrigue making great use of his widescreen frame, never more than in a boldly conceived, extended hand-to-hand fight to the death shot in near darkness. Yet it is the throbbing, bass-heavy audio effects mixing that is his most effective technique, a sound field of propulsive anxiety.

The picture smartly withholds right to its conclusion, eschewing climactic “talking killer” cliches or the usual grandstanding one-liners reserved for those marked for death. Consequently, we wonder what, exactly, does this nameless executioner actually think of himself? In the concluding moment he suggests a hierarchical realization, yet what the picture leaves us with is a person so good at his job and so able to compartmentalize its nature that he has turned murder into a sensible vocation, an art form even, and in doing so achieved unlimited cadres of wealth and the means to travel freely and worldwide as anyone he chooses to be—an American Dream of unlimited autonomy, staring down the barrel of a semiautomatic. Just watch your back.

3 1/2 stars