Kelly Reichardt’s quietly appealing consideration of the life—and life’s work—of an independent artist forms the basis of her new picture, Showing Up, featuring a lovely performance from Michelle Williams as a sculptress navigating the day-to-day while preparing for a gallery opening of her latest collection. It is a movie about the artistic spirit, the kind that fuels the workaday creative, whose life seems invariably filled with banality that can frequently get in the way of creation.

Set in Reichardt’s favorite locale of the Pacific Northwest, Showing Up is a low-key character study of one Lizzy Carr (Williams), a Portland ceramic artist bogged down in a flurry of distractions and complications the week before a big show. Everything seems to be in the way of her designated time to create, principally that her hot water has been out for some time, and her landlord, Jo (a welcome Hong Chau), an artist also preparing to exhibit, is too busy to fix it.

At the same time, her administrative job at the local arts college is a time-consuming headache. After an altercation with her cat leaves a pigeon injured, she reluctantly takes on the responsibility of nursing it back to health. Her father (Judd Hirsch), a formerly successful sculptor himself with parasitical hippie houseguests (Amanda Plummer, Ted Rooney) is divorced from her mother (Maryann Plunkett), who is also her boss. And her brother (a superb John Magaro) is mentally ill and needs to regularly be monitored. When is there time to create?

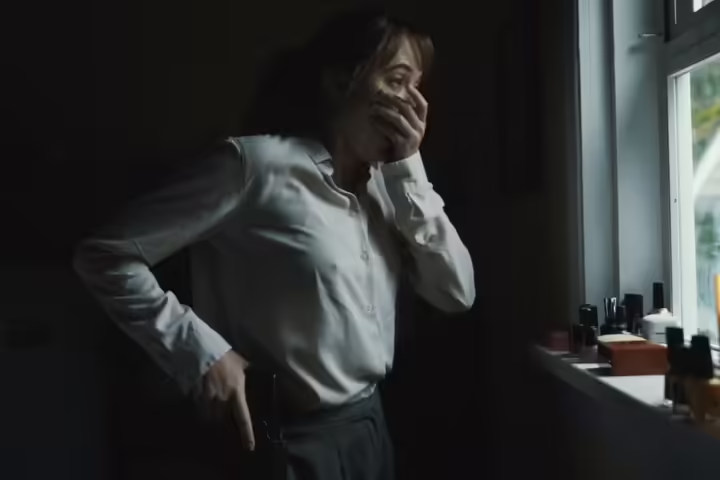

In some of the film’s best moments, Lizzy’s all-night sessions with her fledgling figurines lead to some of the film’s most contemplative passages, inviting us to both consider the artwork, which is given significant due in various stages of creation with long closeups, but also the life of a working artist who is only truly ever engaged in her arena of passion. Williams draws vivid distinctions between the drudgery of routine versus her alert focus while communing with her creations.

It is in such moments that the film gives voice to the convictions of an artist working outside of the commercial mainstream (about which Reichardt knows a thing or two) often with little monetary upside yet fueled by the need to create, which is a madness all its own. Watching Williams’ Lizzy consider every angle with scrutiny, shaping and reshaping, in one moment plucking the arms from a nearly finished sculpture only to refashion something new and novel, captures the notion of what it feels like to go to “that place,” a transcendent channeling of thought, feeling and form into being, always in solitude.

But the real world always comes calling. It does, also, for Jo, who is also wrestling her art into being for her own exhibition, and for whom creation seems a much lighter affair, temperament in direct opposition to Lizzy. She may have the time to fix the hot water but not the mind share; she’s rather install, and swing on, a tire swing behind their apartment building.

Reichardt excels at depicting a community of artists—the academic environment is a swirl of inspiration and an ode to visual art in many forms, including sculptures of all sizes, large canvas abstracts, nude model painting, miniatures and grand scale canvases; the work of real-life artists Storm Tharp, Mike Brophy, JoAnna Jackson and Chris Johanson are featured across the film. One imagines such a community could well be reflective of Reichardt’s alma mater, Boston’s School of the Museum of Fine Arts, or perhaps even Bard College, where she has served as Artist-in-Residence instructor for nearly two decades.

In their fourth collaboration together, Williams is able to convey a very real, modestly scaled person, necessitating that the actress convey conviction in the throes of creative manifestation, which she does with acute precision. She also captures the blasé resignation of someone who knows the beauty isn’t found in mundanity of life’s required routines, but in the luxury of its private moments of invention.

Showing Up is largely free from plot—Reichardt eschews traditional drama in her collaborations with co-scribe Jonathan Reymond—and instead invites us to consider its portrait of a talent unlikely to reach the top of the art world yet one immensely critical to self-actualization. Woody Allen once famously said that 80% of success in life was just showing up, and Lizzy’s commitment to showing up for her passion is an ode to beleaguered working artists everywhere who create because they simply can’t not.

3 stars