There are a handful of moments in Joachim Trier’s The Worst Person in the World where a young Norwegian woman, adrift across professions and relationships, gazes at the Oslo skyline in contemplation of significant life decisions. Has she made the right ones? What is coming next? What will ultimately satisfy her?

If you are unfamiliar with Trier, the forty-eight-year-old Copenhagen filmmaker is the writer and director of such pictures as Reprise, about a potentially suicidal writer; Oslo, August 31, which explored addiction, rehab and damaged relationships; Louder than Bombs, a solemn, American-set examination of a father and sons still reeling years after their matriarch’s death; and the unexpected Thelma, a thriller involving repression and telekinesis.

Accomplished as those pictures may be, The Worst Person in the World is easily Trier’s to-date best in its portrait of a refreshing, disarming and often exasperating modern woman searching for her elusive young identity. This hunt is endearing, romantic, offbeat and then in the final analysis, forceful as a thunderclap.

As navigated by Trier and his effervescent, Cannes-winning star Renate Reinsve, such considerations make for a daring romantic-comedy-drama—one that, if there were justice, would be winning both Oscars this year for Best International Feature Film and Best Original Screenplay.

In a rapid-fire opening sequence, we meet Trier’s romantic heroine of sorts, Julie (Reinsve), who changes career paths and boyfriends on a whim. Initially, she’s a promising med student and future surgeon before abruptly switching gears to psychology. She then abandons medicine altogether in favor of photography. As she tries to explain such high-speed course corrections to her patient mother, we sense her struggling to believe her rationalizations. A similar restlessness informs her love life, switching boyfriends at will from an intellectual, flirtatious college professor to a sexy, gold-toothed fashion model. At one moment she’s a flashy blonde; the next, an earthy brunette.

In this montage, Trier eschews socially expected, young adult milestones in favor of true-to-oneself wanderlust; a try everything, see what fits study of contrasts and exploration—a philosophy that will inform Julie’s subsequent years and choices, with often ambivalent outcomes.

Anyone with an artistic disposition has likely felt this tension, and perhaps looked around the world and witnessed others setting and accomplishing clearly defined and attainable professional or other life goals, often without even questioning them, and making outward strides—dream jobs, big promotions, bright futures and “adulting”—while you’re still doing menial or often mindless work, waiting for real life to begin; the moment when everything becomes clear and your purpose is revealed. As Truffaut once famously said, “Taste is a result of a thousand distastes. “Trier’s Julie doesn’t know what she wants out of life but over time she comes to know what she doesn’t want, which is small comfort.

Trier’s picture spans about four years and is structured as a prologue, 12 chapters and an epilogue, an approach that eliminates standard connective tissue in favor of formative relationships and events.

At a party Julie meets Aksel (a revelatory Anders Danielsen Lie), a cult comic book artist whose politically incorrect creation, Bobcat, has a legion of followers. In his 40s, Asksel has immediate concerns that their relationship won’t last, telling twenty-something Julie, that “If we go on, I’ll fall in love with you. Then it’ll be too late.” Does he ever.

The pair moves in together in classic rom-com fashion, Trier nodding to Annie Hall—a sophisticated and artistic older man opening the mind of a vivacious and offbeat younger woman, here bonding and bantering over how many shelves in his apartment she’s entitled to occupy. Their relationship may not be able to handle two creative geniuses, but Julie is also a budding writer herself, and after penning a radical feminist take on oral sex, establishes some online notoriety.

Turns out Aksel was right about their doomed affair and age difference, and the picture is smart about how easy it is to lose sight of oneself once you become one-half of a whole. He wants kids and is certain she’ll be a great mother; she has little interest. In a most painful breakup scene extraordinary in both tenderness and frankness, Aksel cautions Julie that what they have is special, and being nearly 15 years her senior he knows from rarity.

She leaves for a much younger barista, Eivand (a charming Herbert Nordrum), whom she’s met by chance upon crashing a wedding reception. In one of the film’s most intoxicating sequences, they dance around a heated flirtation careful not to veer into actual cheating, the line to which keeps getting fuzzier. Trier mounts a grand, theatrical sequence where time stands still—literally everyone on the streets of Oslo freezes while Julie races across town and into Eivand’s coffee house, upon which the pair fall helplessly into each others’ arms. Against a backdrop of frozen city dwellers, they stay up together until dawn, in mutual reverie.

When they first meet they are both with others—Julie with Aksel and Eviand with high-maintenance yoga guru Sunniva (Maria Graza de Meo), whose obsession with social causes pushes him out the door. As Eivand says, “I’m the worst person in the world,” a self-effacing embrace of guilt.

They have chemistry but little intellectual stimulation and eventually Julie goes sour on Eivand as well, dissatisfied with his apparent lack of ambition. There’s a stunning moment in a gym when she catches ex Aksel on television panel railing against a female-led inquisition about the political correctness of his artistic vision. For Julie, this moment draws a stark contrast between both men—the accomplished, older, passionate artist and the happy-go-lucky, younger barista. Hypnotized by the televised discourse, she appears to wonder if she made the right choice.

The final act of The Worst Person in the World is almost unbearably moving, and contains a rumination from Lie (who has been in three pictures now for Trier) about growing up in a different generation, and the fading glow of nostalgia: “I grew up in a time when culture was passed along through objects. They were interesting because we could live among them.” Anyone who came of age in the 80s will feel a shiver of sadness, Lie beautifully etching out a clear-eyed confrontation with mortality featuring the best dialogue in a movie this year.

Trier deploys innovative technical flights of fancy across this picture finding ways to enliven Julie’s continuing neuroses, including the slow motion sequence, a spare voice-over narration and a marvelously funny sequence where she goes on a mushroom-fueled drug trip manifesting all of her anxieties at once.

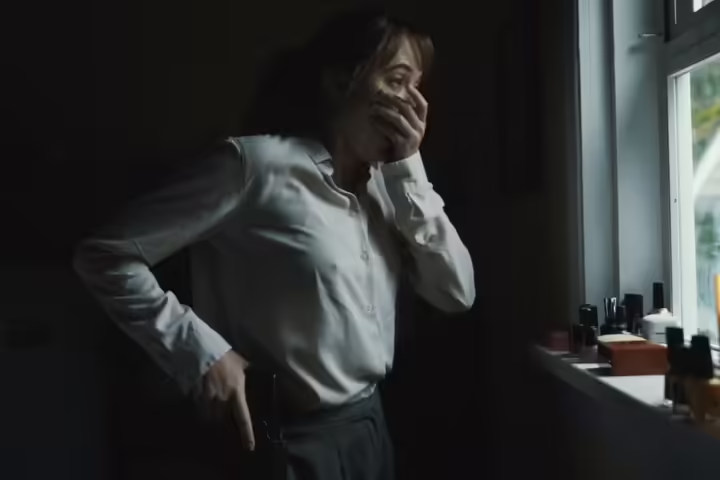

Reinsve is positively radiant throughout, and one of the keys to her performance is how Julie’s evolution is on her face; Trier and co-writer Eskil Vogt never give her a monologue to explain her feelings or to enlighten us to any evolved sense of self. Instead, Reinsve delivers Julie’s eventual growth with a measured stillness and compassion suggesting, by the film’s close, that she knows exactly where she’s been, what has been important and where she is going. In her remarkable late scenes with Lie, she suggests an unmistakable awakening and clear selflessness. This is all in the performance.

“You’re a damned good person” Aksel tells Julie in the former lovers’ wistful parting. As played by Reinsve, she is a damned memorable one of the kind we wish we knew in life.

4 stars.