Quentin Tarantino’s Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood—a gorgeous evocation of 1969 Los Angeles and bittersweet elegy for falling Hollywood stars and the passing of a definitive American era—is the work of an artist at the peak of his powers, which, if you believe him, will be too-soon shuttered into retirement.

Say it isn’t so, Quentin.

Because in Once Upon a Time … in Hollywood, a bona fide movie love letter to the dream factory that made him, melancholy ode to buddy pictures and daring mash-up of historical fiction and real-life events that dovetail into a payoff only this auteur could dream up, the director has made perhaps his most mature, wistful, work. It’s fast and loose, funny and a touch sad, a little unnerving and finally redemptive.

Here is a picture with the audacious wherewithal to juxtapose a featherlight tale of whole cloth artifice (ok, perhaps inspired by a few real life folks)—a Hollywood actor on the downslide (Leonard DiCaprio) taking his longtime stuntman (Brad Pitt) with him—alongside a very painful chapter of American history, the combination of which proves something unexpected, and nearly transcendent.

Picture opens in February 1969 in a retro-fitted, vintage Hollywood, impeccably recreated to depict a gleaming Tinseltown on the verge of change, soon to be upended (as will American culture) by hippiedom—a world personified by desperate B-listers, fledgling movie stars and nubile vagabonds, all flitting around the L.A. scene.

Fading 1950’s television cowboy star Rick Dalton (DiCaprio) has seen better days, his career on fumes after the cancellation of his popular TV western, Bounty Law, and a failed-to-ignite movie career. An insecure wreck prone to drunken, self-pitying crying jags, Rick trades on his remaining public goodwill by making the rounds on a series of cornpone TV interviews and weekly variety hours. But even he knows things are rapidly downshifting.

Rick’s neuroses are exacerbated when salty agent Marvin Schwarz (Al Pacino) declares him industry persona non grata (while offering to make him bankable again in Italian Spaghetti Westerns). With his glory days (which he frequently relives via late night television reruns) in full rear view, his only consolation is best buddy, career stunt double, driver and, in a pinch, handyman Cliff Booth (Brad Pitt). It’s been reported that their kinship is a nod to Burt Reynolds and Hal Needham (maybe, maybe not), and the stars have an easy chemistry, one of this picture’s primary joys.

Rick lives up on infamous Cielo Drive (a sign for which provides pit-of-the-stomach queasiness), but his pad is well below that of his more famous neighbors, starlet Sharon Tate (Margot Robbie) and husband Roman Polanski (Rafal Zawierucha), hot off Rosemary’s Baby, whose up-the-hill, gated abode affords Rick hopes of party invitations and career resuscitation. So close, yet so far.

Booth, on the other hand, lives in a rundown trailer behind the Van Nuys Drive-In (incandescently reimagined), eking out a living on Dalton’s back, but as the leading man’s fortunes reverse, so does his own livelihood. A cool customer who spends nights getting drunk in front of the TV with his faithful pooch, he’s also got a legendary rep as a premiere badass, having (maybe) killed his first wife, the lore of which intimidates a bigtime producer (Kurt Russell) that wants him off the lot. Comically complicating matters is Cliff’s public dust up with Bruce Lee (Mike Moh), talking smack on the set of The Green Hornet. Tarantino, a Bruce Lee aficionado, comically takes the legend down a notch.

Rick eventually catches a break on a hit show named Lancer, the shooting of which gives the picture two comic highs. First is a meeting with a studied, eight-year-old colleague (terrific Julia Butters) who schools her elder co-star on the art of method acting; the second an uproarious, extended sequence where Rick, opposite Timothy Olyphant as the series’ workmanlike star, can’t remember his lines.

What follows is a spectacularly funny meltdown of self-recrimination and flagellation. This scene, and a subsequent moment where Rick delivers the best acting of his career, is high-order, movie star stuff, the kind which few but DiCaprio can deliver, knife’s edge absurdity both riotous and poignant. The star, whose performance as a slave-owner in Tarantino’s Django Unchained was a similarly wily piece of comic and dramatic exaggeration, is fully liberated by a director who embraces artifice, and able to go big, and small, almost at once.

When Cliff isn’t chauffeuring Rick around town or shirtlessly fixing his buddy’s TV antenna, he’s tooling around the Sunset Strip in his boss’ pale yellow Cadillac, flirting with a ubiquitous hippie chick named Pussycat (Margaret Qualley), who cons him into a ride home (sensing she’s underage, he rejects a sexual come on), the infamous Spahn Ranch, hoping to introduce him to one Charles Manson (Damon Herriman).

And that development turns the picture from affectionate industry lark to something darker. Even without our hindsight Cliff knows something strange is afoot, and even though he once made pictures at the dusty locale, he must fight his way past a tough talking Squeaky Fromme (terrific Dakota Fanning) to reconnect with old friend, and now senile ranch owner, George Spahn (Bruce Dern).

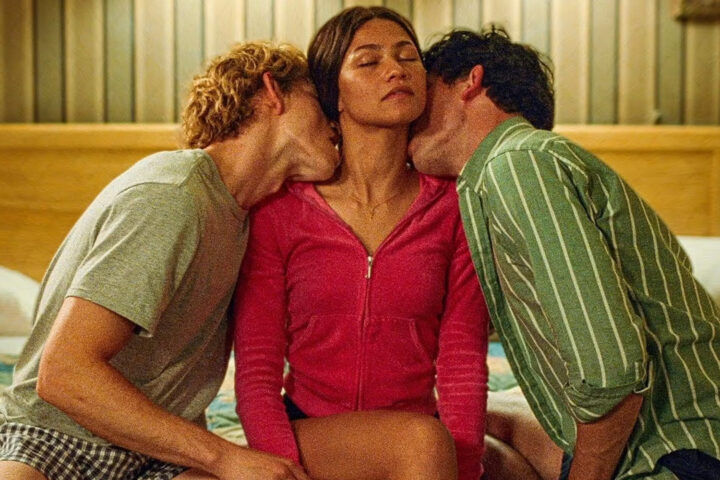

On the periphery of all this is Tarantino’s vision of an on-the-cusp of stardom Tate as a disarmingly gentle soul who, in one lovely sequence, wanders into a Westwood movie house to catch her performance in the recent Dean Martin starrer The Wrecking Crew (we see the actual Sharon Tate projected in clips), propping her bare feet upon the seat in front of her. Robbie’s wide-eyed, personification of goodness and grace offers consideration of who Sharon Tate might have been, had she not become synonymous with a heinous tragedy. In an unexpected way, the movie restores her humanity, dispensing with an unfortunately accepted identity cemented 50 years ago.

Cliff’s visit to Spahn Ranch also raises our anxiety levels in preparation for the picture’s final third, which follows the duo’s reluctant Italian stint shooting a pair of Spaghetti Westerns. Those pictures make bank overseas and even net Rick a hot-to-trot, Italian co-star wife (Lorenza Izzo), but upon returning to California in August 1969, he’s no fool about the future of their long-time collaboration. Winds of change are a comin’.

And in this film, that means the Manson Family, wandering up Cielo Drive, brandishing bravado, blades and bloodlust. While the women aren’t named, it is easy enough to surmise surrogates for Patricia Krenwinkel, Susan Atkins and Linda Kasabian alongside Tex Watson (Austin Butler). What isn’t easy to guess is what happens next, which all but delivers the movie, and is certain to be talked about, debated and, likely, cheered.

The less said about this final act the better, but suffice to say that Tarantino goes all out to deliver a galvanic, violent denouement that will undoubtedly polarize some audience members, a gonzo gut punch involving an acid laced cigarette, bloody retribution and a revisionism (this is a fairy tale, after all) that just about all of us can get behind. Despite the mayhem, a final, poignant scene suggests redemption and hard-won wish fulfillment.

Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood, with its titular nod to Sergio Leone’s famed Western, is a Tarantino picture through and through, meaning references to drive-in flicks, vintage television, deliberately provocative music cues (including a well-placed California Dreaming), intentionally written dialogue (though this time his often too-clever monologuing is kept in check), a bit of hyper-violence, glossy artifice (there’s a breathtaking sequence late in the picture where dusk falls on the Sunset strip, bathing the town in the glow of flickering neon) and an absolute, 35mm movie-movie sheen, courtesy of famed DP Robert Richardson.

And one simply has to marvel at Tarantino’s lavishly mounted, vintage Hollywood set-pieces, most notably a fab recreation of a Playboy Mansion bash worthy of Jay Gatsby, complete with go-go boots and miniskirts, Michelle Philips, Mama Cass and Steve McQueen (Damian Lewis), through whom Tarantino theorizes an entirely plausible dynamic between Tate, Polanski and the late Jay Sebring (Emile Hirsch).

But since it’s a movie about Hollywood, a pair of movie stars really sell it, especially DiCaprio, high wiring his performance from knowing satire to genuine pathos, never better than when shedding tears after delivering an unexpectedly brilliant turn in pulp material.

And Pitt, who is always best when he’s allowed to be Pitt, or at least the laid-back, funny version we’ve seen in pictures like Burn After Reading and Tarantino’s own Inglorious Basterds, is so smooth here and fits into his second string character with such relaxed charm, it reminds you that the smartest movies stars have always tethered their innate charms to their characters, rather than the other way around. Well into his fifties, Pitt has still got it. The camera knows it, and so do we.

In the end, there is something transporting about Once Upon a Time … in Hollywood, which in allowing its flailing protagonist to reclaim himself does the same for the romance of a long-gone era of Hollywood moviemaking and Americana, suggesting that artists, however marginalized and from whichever tier, can, in the most unlikely ways, assuage the evils that men, and women, do. Tarantino clearly adores his strivers and dreamers (and while they are played by A-listers, they are never sport), particularly the leading lady that would have skyrocketed but for the intervention of cruel fate. The picture is a revival, and reverie, for a woman whose goodness and talent, rather than demise, finally defines her.

4 stars.