James Franco’s The Disaster Artist is an unexpectedly near-great movie and one of the funniest pictures ever made about the process of making movies. In telling its loopy, endearing tale of ambition minus talent in Hollywood—of which there’s certainly no shortage—it manages to lampoon both moviemaking and the artistic ego, painted as a wistful sort of reverie for a guy who had a lot of heart, even if he has no business in the movie industry.

In a massive stroke of irony, an A-list production derived from a grade Z picture may actually make The Room creator Tommy Wiseau, the mostly bizarrely fascinating of characters, into some sort of star and garner Franco a well-earned Oscar nomination in the process.

Fans of The Room—and I’d count myself amongst them—well understand its B-movie paradox of accidental inspiration in its complete and utter awfulness, a movie that Wiseau took very seriously and is, above all, a complete misfire in every regard, to the tune of a whopping $6 million budget.

A laughably awful ode to true love, betrayal, bromance and surrogate parenting, the wretchedness of The Room, a disaster made by people who thought they were shooting the Great American Movie, must be seen to be believed—melodramatic, laughable, poorly “acted,” naive and cheap, despite its price tag. And thank God it was made, otherwise we’d never have had this very good movie.

Franco’s film, based on The Room co-produce and star Greg Sestero’s 2013 account The Disaster Artist: My Life Inside The Room, the Greatest Bad Film Ever Made, isn’t the condescending trip one might expect (and would find in a lesser film this year like I, Tonya). When it isn’t having a good laugh at its decidedly insane lead character, it approaches something oddly touching in its story of an enduring friendship between two starry-eyed, misfit bros who meet in an ill-fated San Francisco acting class in 1998and bond over James Dean before hitting the road to Hollywood, certain of their impending success. There’s real heart in this picture of two losers who can’t catch a break—so they decide to make their own.

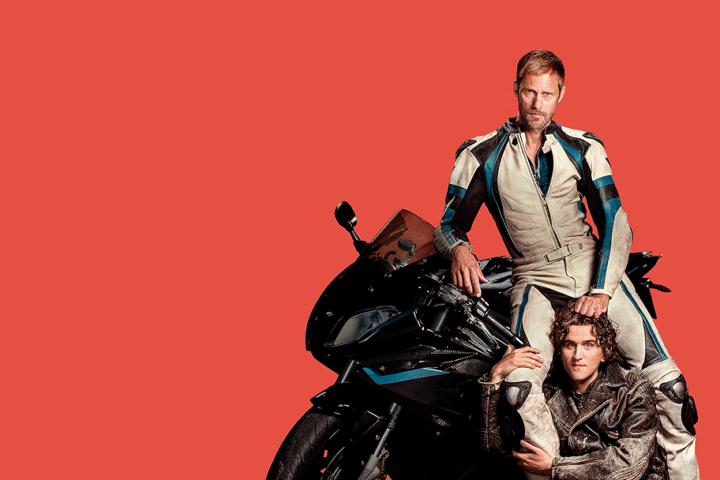

Tommy Wiseau (Franco) is a really, really strange guy who will share nothing about his past or from where his considerable bankroll comes. Looking like a Transylvanian reject and sounding Eastern Bloc, he nevertheless assumes a ruse of being a New Orleans native and when we first meet him, he’s writing around acting class, a go-for-broke Brando impersonator and the personification of a car wreck, alternately repulsive and enigmatic.

It’s here he meets hapless, benignly good looking “baby face” classmate Sestero (Dave Franco, in good nature and humor), convincing him to strike out to LA together despite Wiseau’s decades-older appearance (though he insists they are “the same age”).

Sestero is quickly signed by a useless agent (Sharon Stone, having fun) but finds himself unable to get work; Wiseau can’t even get one, and after being tossed out of a tony eatery for hilariously accosting Judd Apatow, Franco presents this struggle seriously, shrewdly knowing just when to play the pathos straight.

The solution to their troubles? To do it themselves, naturally, and Tommy’s mysterious, bottomless bank account combined with his shallow abilities set the stage for a godawful production—The Room—in which no expense is spared, and no talent employed. Wiseau can’t be bothered with the fact that everyone else may be right that he should never, ever be in movies, a widely-held belief he dismisses outright.

Penning his labor of love screenplay, he quickly buys expensive camera equipment and hires a sprawling crew to recreate silly alleyway sets and tacky green screen effects, as well as a supremely untalented cast—played with relish by the very talented Ari Graynor, Jacki Weaver, Josh Hutcherson and Zac Efron—as well as a script supervisor, delivered with the usual deadpanning by Seth Rogen. No budget expense is spared, but the AC and water certainly are while tensions flare over the troubled production, complete with gratuitous sex scenes, nudity, laughable male bonding and “hero” Tommy’s inability to remember his lines.

The second half of the picture is a looney tunes series of set-piece recreations and anyone who has suffered through Wiseau’s enjoyable misfire will get much pleasure from Franco’s restaging of its predecessor’s awful moments in scenes that allow Franco to cut lose in what can only be described as narcotized mania.

If all of this sounds like hijinks and sitcom set-ups, it isn’t—screenwriters Scott Neustadter and Michael H Weber have crafted a feat of conceptual inspiration and a decidedly humanist character comedy as much about friendship as farcical sendup. Perhaps because its real-life Franco brothers are playing so well opposite each other the picture has a sincerity and freshness that manage the neat trick of actually getting us on Wiseau’s side—much credit to Franco in the role—even though we know he’s headed for a disastrous, crash and burn premiere.

But getting there with him is tremendous fun in this sweet, funny movie.

3 1/2 stars.