You really have to hand it to director Alejandro Gonzalez Inarritu, whose films never cozy up to their audiences, instead demanding a partnership that can be agonizing in the moment but always haunting, enlightening even, upon reflection. With a handful of rigorously commanding movies under his belt, from the accomplished Mexican triptych Amores Perros to the grimly interlocking 21 Grams and onto the global parable Babel, he won the Oscar last year for his audacious actor’s redemption tale, Birdman. Each of those pictures was so good one might be inclined to forgive his oddly vacuous misstep, the Barcelonan criminal saga Biutiful. Structural marvels both thematically and narratively distinct, each found Inarritu pushing himself, and his actors and crew, into dark and uncomfortable places for our viewing pleasure.

In the case of his new film, The Revenant, he all but thrusts us headlong into this darkness with his brave company, and for some this test of endurance will prove demanding. But those who stick with this story of survival and revenge set against the unforgiving backdrop of a brutal American West frontier, will be rewarded with perhaps his best, and one of the year’s very best, films. Regardless of how you interpret this challenging, arty adventure of a movie, you have never seen anything like it, a you are there, close to the ground aria of endurance grounded, literally, by star Leonardo DiCaprio. It is painful, powerful stuff.

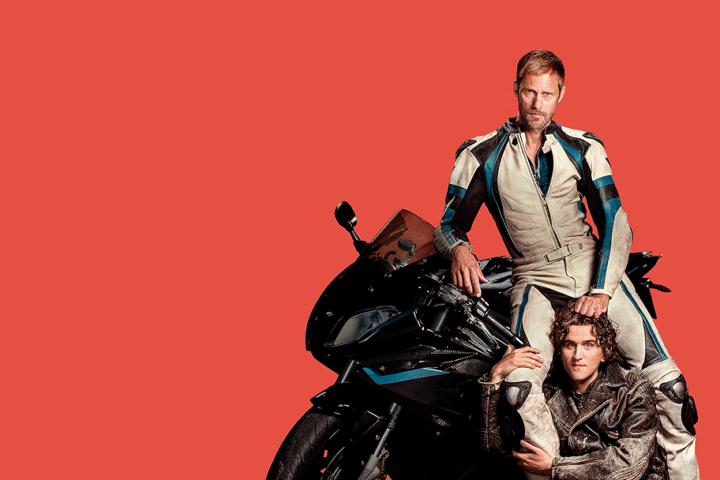

DiCaprio is real-life fur trapper Hugh Glass, member of a hunting party crossing the 1823 wilderness of the Louisiana Purchase when, in a staggeringly choreographed and shot opening sequence, the men fall under attack from hostile Native Americans. Under the guidance of their stalwart captain (an excellent Domhnall Gleeson), the surviving men take to the river before heading deep into the forest. The ragtag, exhausted party includes racist, thug and killer John Fitzgerald (Tom Hardy), resentful of Glass’ half Native American son (Forrest Goodluck) and greenhorn Jim Bridger (Will Poulter).

When a savagely ferocious Grizzly mauls Glass to death’s door in a scene of elemental force, the party’s already daunting mission to return to their fort—on foot, across the wintry Rockies—is effectively compromised. With Glass bleeding from every limb and most of them broken, Fitzgerald and Bridger accept a premium to stay behind. But Fitzgerald has other plans, and after smothering Glass and murdering his son, convinces Bridger that Native Americans are in pursuit, leaving near-invalid Glass for dead. Thus begins a survival epic like we have never seen before, one both viscerally powerful and spiritually transcendent.

Unable to walk, Glass initially crawls his way out of a shallow grave, but adding to his troubles are the Native Americans, whose chief is looking for his own kidnapped daughter, taken prisoner by a team of French explorers.

There’s much, much more—a frightening fight to stay alive in rapids, near starvation and hypothermia, a kinship with a friendly Native American who shares raw buffalo and saves Glass’ life and a spectacular sequence involving a horse going over a cliff and its body hollowed out as shelter. Meanwhile, Fitzgerald returns to the fort, spinning a tale to obtain a cash reward. But it isn’t long before the film sets up a doozy of a mano-a-mano, the excellent Hardy a most formidable foe.

This cursory plot outline can’t come close to what it means to experience The Revenant, a complete immersion into grime, water, snow, cold and fear, and much of the credit is due to Oscar-winning cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki, whose camera captures both the grittiness of survival as well as transcendent moments of spiritual awakening, some of which recall his work with Terrence Malick on Tree of Life. Employing only natural light, the film was shot across three countries, the majority around Canada’s Calgary, a bit in the United States and then its climax—featuring a real-life avalanche triggered for a key moment—in Argentina after the Canadian snow had melted. And veteran Japanese composer Ryuichi Sakamoto’s less-is-more score is minimal and unnerving.

But the real credit for delivering The Revenant goes to star DiCaprio, who takes a non-traditional role—survival against the elements, essentially—and somehow, through sheer force of will in a largely non-speaking role, wears all of the terror and pain on his face, windswept, cracked and weary. But to say he merely survives would be to shortchange his commitment here, which included eating raw meat, freezing in raging waters and sleeping in animal carcasses, but also his depiction of a spiritual rebirth and communion with nature. And special mention should be made of Poulter’s babe in the woods, a sort of innocence lost conscience and moral center, a performance that forces us to question whether any such sentiments were merely luxuries in as brutal a milieu.

Inarritu, of course, is not keen to deliver a scaled down survival and revenge movie, and as complex as his other pictures have been, The Revenant is no exception. The depiction of Native Americans is rich enough to suggest social codes, familial loyalties and value structures, and the assertion that both American and French settlers were (are?) invaders that took, and then raped, is pointed.

The terrifying, gorgeous experience of a movie is as transformational as films come, and its power to take us somewhere very specific in time but also to somewhere emotionally universal. As a portrait of endurance and rebirth, The Revenant is mystical, poetic, majestic and brings us as close to death as a movie can, right to its final, wall-breaking shot.

4 stars.