Samba, the good-hearted story of a Senegalese immigrant in Paris fighting deportation, is a sum of its parts picture. Written and directed by the French duo Olivier Nakache and Eric Toledano from the novel Samba pour la France by Delphine Coulin, it’s a movie that means so well you feel half-bad for nitpicking its shortcomings, obvious as they are.

In 2011, Nakache and Toledano hit the big time with the race and friendship story The Intouchables, the true tale of a down-on-his-luck nurse to a millionaire quadriplegic, and star Omar Sy took home the Cesar for his effervescent work as the caregiver with so much to give. The picture—and his performance—were also rewarded with a global box office of $426 million, making it the biggest box office hit to ever come out of France. But Samba doesn’t reach the heights of their previous collaboration. Like The Intouchables, it’s a movie that uses humor to diffuse a serious subject—in this case the struggle of immigrants—with somewhat less successful results.

As Samba, Sy again delivers a portrait of struggle and humor with heart. In Samba’s opening shot—a good one—we move from a lavish Parisian wedding celebration into the kitchen efforts of work and sweat from the immigrants behind the scenes, notably Sy’s titular dishwasher, a Senegalese immigrant who dreams of being a chef, soon detained over his lack of a Visa. And it’s in these opening scenes that the picture is strongest, depicting lower-rung dreamers whose efforts are rewarded by jail, sharing hardscrabble stories, their fates on the ropes.

Enter novice immigration advocate worker Alice (Charlotte Gainsbourg), who promptly fixates on Samba’s case and charisma, which is considerable, herself a damaged woman recovering from a breakdown after a high-powered career in business. The pair have immediate chemistry, and once Samba is released and instructed to self-deport, they grow closer in Gainsbourg’s best scene, a long talk about work and burnout, and costs of defining yourself by what you do. Samba himself knows something about this.

And therein lies the rub—while both actors are terrific, the story immediately gets off track once Samba leaves detention and the movie shifts to their relationship, which is not all that convincing and deflates the opening’s sincere exploration of the immigrant experience. There is also a tonally ineffective comic subplot involving another immigrant, Wilson (Tahar Rahim), posing as a Brazilian to win women while washing windows with Samba, culminating in an unnecessary rooftop action scene. And still, the screenplay introduces another throw-away thread as Samba searches out and sleeps with the lost love of his inmate friend, the revelation of which drives the film’s final reels far afield from the film’s solid opening.

Samba isn’t a movie about the immigration crisis in France, where an estimated 300,000-400,000 workers are undocumented, rather, it’s a movie about personal identity, assimilation and our relationship to our work—in other words, about self-definitions and reinvention. Some of this is compelling and some less than, and the two-hour running time feels a bit indulgent, with supporting characters not all that memorable and the love story a detour from the admittedly darker realties of the immigrant experience.

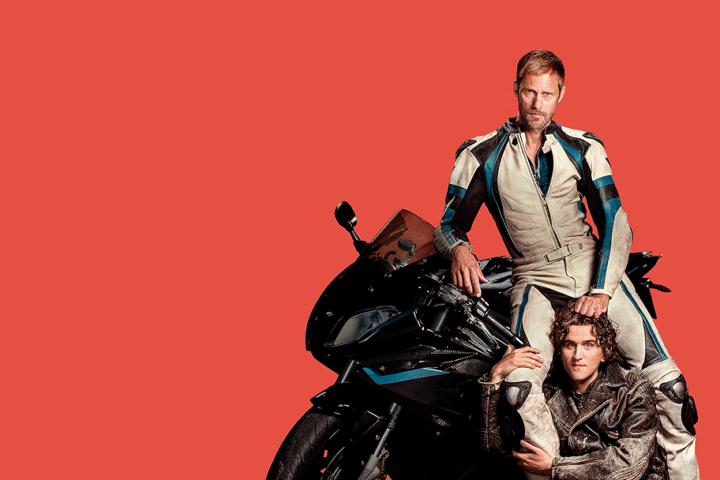

Yet despite Samba’s tonal swings and slackness, both Sy, the megawatt beacon and Gainsbourg, the most delicate and emotionally acute of actresses, deliver characters worth caring about. Sy, especially, with his lean physique and persuasive smile, can sell even the most questionable scene, a public shouting match between Samba and Alice that feels more written than real.

Strong set-up, meandering middle and an acceptable conclusion make Samba a less than successful movie, though the pleasures of its leads are undeniable.

2 1/2 stars.