American Sniper, an acceptable if lesser Clint Eastwood picture based on Navy SEAL Chris Kyle’s memoir of four tours in Iraq, is a movie with a lot going for it.

It’s got Eastwood at the helm delivering a sometimes muscular movie with modern political relevance and ideas about heroism and nationalism; a good performance from Bradley Cooper as the gung-ho Texas rodeo cowboy whose rock-solid ideology and unmatched sharpshooting took him straight to the center of the conflict; and a sometimes effective meditation on loss of idealism and subsequent traumas associated with PTSD. But for those merits, it’s a movie that doesn’t ever examine its most obvious and important theme—the complexities of killing, and what that does to the soul—and as a result, it feels like a bit of a cheat.

Unfortunately for this movie, all of this has been covered before, and recently, in far better movies like The Hurt Locker and Zero Dark Thirty. Consequently, the timing of American Sniper combined with its inability to shed new light on these topics renders it unnecessary.

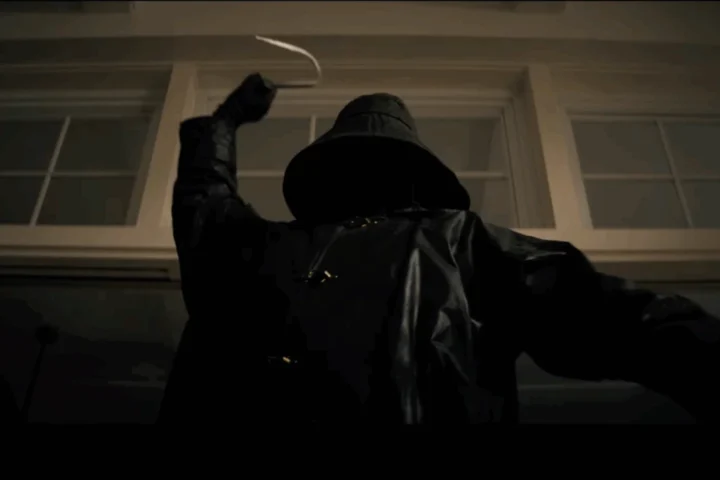

It’s a movie that gets high on the adrenaline of the kill while trying to present some sort of muddled moral dilemma, and Eastwood gives us a few effective sequences—like an opening one, for example, where an Iraqi mother may just have a grenade ready to pass to her young son, also a mark—that play somewhere between Kathryn Bigelow’s Oscar winner and Call of Duty: Modern Warfare.

American Sniper never pretends to offer a complex view of war, presented here as one of heroes more than hell, and one in which Kyle, played by a buffed-up Cooper as a good-old-boy who knows he is “right with God” and is equally certain on the trigger with largely one-dimensional Iraqis, written by Hall as nefarious warmongers that deserve their fates. For a character study about a veritable killing machine, it seems curious that Kyle never questions what it means to kill scores of people. And one can imagine that Eastwood essaying such a topic here might have been fascinating.

With a screenplay by Jason Hall, the film travels two geographies and threads—one a visceral, you-are-there account of Kyle’s involvement in Iraq (he was purported to have killed hundreds during his tenure); the other, his involvement with long-suffering wife Taya, played by a terrifically alive Sienna Miller who is given very little to do other than worry, pine and generally nag Kyle during his returns home, which are also piqued by some garden-variety PTSD scenes, none of which prevent him from re-upping for the next tour.

As Kyle’s combat legend grows (he’s actually nicknamed “Legend”), his marriage suffers, complicated by the arrival of children. With God and country number one, the consequences of such on the marriage are explicitly rendered in a scene involving a telephone and an unexpected hail of gunfire.

Yet American Sniper is a surprisingly routine picture from the 84-year-old director, who seems uninterested in examining either the moral implications of killing or motivations of such a person, which seem wholly triggered by watching the twin towers fall on television the morning of 9/11.

But Cooper gives it his all, investing real feeling into scenes such as one harrowing moment involving a child who picks up a weapon at just the wrong moment, or in some wearier stateside passages where he sits alone in bar, simply unable to return to his family.

The picture ultimately feels hamstrung, with Hall and Eastwood unable find a compelling balance between the film’s sometimes gripping war scenes and the domestic ones, or take much of a position about either. Back and forth Kyle goes, and as the tours go on, the most interesting dimension here is how Kyle’s rock-steady patriot observes the growing attitudinal shift within his band of brothers, themselves gradually losing faith in conflict and country.

American Sniper traverses familiar movie territory and offers few new ideas in either the filmmaking or narrative. And its inability to effectively deal with its coda on Kyle’s fate is a real misstep.

2 1/2 stars.