In two films together, writer-actress Brit Marling and writer-director Zal Batmanglij have explored issues of identity, and both spiritual and cultural alienation. Distinct and intelligent, both 2011’s Sound of My Voice, about a mysterious Los Angeles cult leader (the transfixing Marling) and their new film, The East, about an “eco-terror” faction targeting environmentally negligent corporations and the rookie spy who gets herself tangled up in their politics, mark an exciting new brand of thoughtful, reflective, relevant thrillers.

Where Hollywood pictures today are all about blowing things up, Marling and Batmanglij dig deep into personal and political ideologies, and the costs of treading into hermetically sealed worlds that inevitably shift the ground beneath your feet.

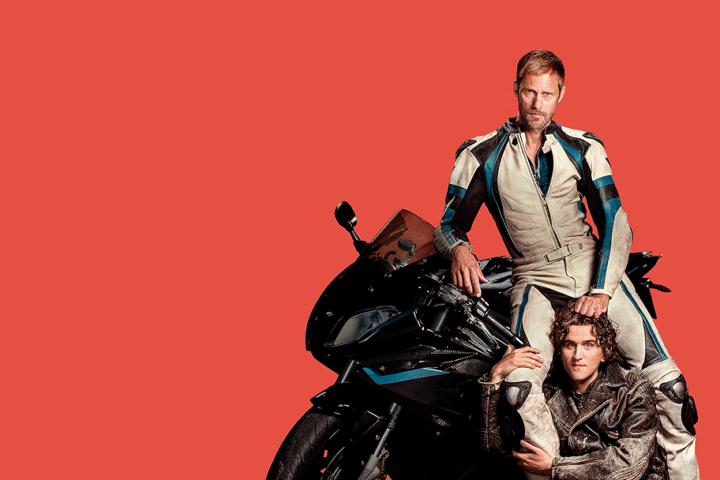

I recently caught up with the pair, real-life partners and co-muses, it would seem, to chat about The East. Marling, a Georgetown grad with an Economics degree who eschewed a big business career for the nourishment of sleeve-rolling, hat-wearing independent film production, hitting big with 2009’s Another Earth before going on to substantial commercial roles in pictures like Arbitrage and The Company You Keep, stars in The East as an intrepid novice agent in over her head. It’s a classic suspense set-up and a showy, engrossing performance.

Our discussion raised issues of political polarization in the U.S. today, gender inequity in American films and our latitude as human beings to cut through opposing philosophies and really see others in an increasingly remote world, making for an unusually substantive discussion, this being a press junket after all.

One of the most exiting things about this movie was how my sympathies shifted back and forth throughout the film. And I was forced to actually reexamine how I interpreted the anarchist activities in the movie. I suppose it made me question what the word ‘terrorism’ means, something we hear so much about today. It was very unsettling.

Brit Marling: Well, that was really excitingly put! It’s so nice to hear that the movie made you feel that, because I think Sarah’s journey is similar. I think she is a person who really feels that she knows what justice is and what is good, bad, right and wrong, and then I think as she has this experience undercover and infiltrates this world, she finds a very complex moral gray zone and what it is that you can stand firmly behind is hard to know.

Zal Batmanglij: I think that we as people feel that too. We live in a morally gray world. I think generations ago it may have been easier—or maybe that was just a myth—to see things clearly; what was right and wrong. But I think it’s harder today to know how to get out of things that we are in. I am constantly reading things on my computer and I don’t know what the answer is. We have all of these sorts of paradoxes about how to ‘be’ in the world.

You’re once again dealing with issues of identity and being undercover in a hermetically sealed world.

ZB: They were written around the same time. I think that both Sound of My Voice and The East are both interested in identity and fascinated by the idea of deep cover as a metaphor for how we feel in our 20s, as we try to figure out who we are. We put on these hats—we put on the hats of filmmakers and you put on the hat of a journalist—and we go through these undercover personas.

It’s also a more ambitious film than Sound of My Voice, both in theme and approach.

BM: On this film we didn’t really have that much time and it was ambitious—lots of locations, huge cast, stunts going on and shot in 25 days—but it didn’t feel that different from Sound of My Voice in the sense that we were still moving fast and every day when I would look at the call sheet, I would think there was no way that we would make it. And then Zal would pull it off. But I don’t think that we strayed far from how we feel about making films, which is that everyone is going to have to roll up their sleeves and wear a lot of hats and come to the project because they love it, and that is the energy that creates a tribal feeling whether it’s for $100,000 or a few million. If people are coming to the set not because they are getting a paycheck or feel it’s the right career move, but because they feel the story has meaning and for that period of time gives their lives purposes, that kind of energy on set is contagious. We felt that way every day. We feel it even right now in talking about it. All of the actors are excited to talk about it because it doesn’t feel like you are selling something, but it is something you are interested in talking about.

Today we live in a world where we see things in black and white, blue or red, Republican or Democrat. But I think the most provocative and hopeful message in this film is that as Sarah gets close enough to people who may have different political or social beliefs than she has, she is able to cut through all of that stuff and get to the human part of how we are actually supposed to relate—person to person. It’s a very important message, in my view. It’s no longer about who is ‘right’ about anything.

BM: Totally.

ZB: I have never heard that before. That is interesting. That is really interesting because that is the true quality of our times right now, isn’t it? We have more access to information than ever before; our opinions are more reified than ever before. I heard Bill Clinton speak recently, and he said, in his southern drawl, ‘I don’t know what the latest American affliction is—we can’t even stand to be around people who think differently than we do these days.’ And that is so true. We cannot be around people who think differently than us. It was a shock to me when I saw the racial hate from kids and teenagers when President Obama got elected the second time. I could not believe people who talk like that on Twitter in a public way. I thought, ‘Wow, I must live in a super sheltered place if I can’t comprehend that this exists.’

BM: Did you use the word ‘reifying?’ This idea of tunnel vision is because the world has become so complex and such a gray zone that nobody wants to look. It’s like a thoroughbred racehorse with the blinders on, and you just keep running around the track. And it’s like, don’t take the blinders off and take in the race or what you are actually doing, but just keep racing for the pleasure of winning. And it’s a weird moment if you allow yourself to take the blinders off and engage in the conversation and really listen to other people instead of just talk.

It’s rare in these times. I recall during the election last year that friends of mine actually asked their Facebook friends to unfriend them if they supported the opposing candidate.

ZB: But I also kind of agree with that. I also kind of agree that people who were supporting whatever his name was… I can’t even remember what his name was—Mitt Romney—were they on crack?

BM: But the other weird thing is that what is interesting about this movie is that it doesn’t seem to matter if people are on the far right or far left or anywhere in between—everyone seems to agree right now that something is amiss with corporate greed. Everyone feels the BP oil spill was handled badly. Nobody seems to think it makes sense to put dispersant to get rid of the oil for photographs from above when the dispersant is a worse chemical, in many ways, than the petroleum. It’s all gotten weird and muddled. And that’s why it’s interesting to talk about this movie with people on both sides of the political spectrum, because the one thing that everyone can agree on, if there is anything to agree on, is that…

ZB: …it’s a frustrating time.

BM: It’s a frustrating time, and certain things seem so powerful they are almost unassailable. And how do you make people accountable?

ZB: And we are out of sync. Something is wrong.

Brit, you experiment with some near James Bond-level skills in this movie. Could you really swallow a Listerine breath strips container?

BM: I tried to swallow the Listerine thing. I went to Walgreens and tried to figure it out. I think it can be done, but you have to really relax!

ZB: We tried a lot of things. With the paperclip thing, I remember being at my desk and Brit was on the sofa, and I threw her a paperclip and said, ‘How long will it take you to open it up in your mouth?’ A couple days later she came to the writing room, and would put the paperclip in her mouth and it would come out like this thing, and I would just film it on my iPhone.

It seems to me that The East is, at times, a probing movie that questions how certain things can happen in a country like ours. It seems necessary to dole out punishment in the context of the movie. Yet you almost feel sympathetic for the corporate figures, particularly during that pivotal scene on the bank of the pond.

ZB: The kids dying from their bathwater from cancer is true. So you read about that and you see pictures of the kids and your heart is broken. And you feel like, ‘How can this be in America?’ So you want to put the CFO or COO of that company in the chemical water. So you have this group who does that in your story, The East. Then he says, ‘I am going to go in myself.’ Brit and I were like, ‘Okay, that’s not exactly what we wanted.’ But when you imagine this you see it so richly, and this guy is there, embarrassed in front of colleague that his daughter is doing this. It’s unclear whether the colleague knows what is going on. And he is trying to- I think that some people in these corporate positions are obsessed with power and one little touch of power. So he wants to sort of take over the situation somehow. So he gets the water himself and when he does, I think a lot of people who are very wealthy and successful are insulated from reality, and I think when he is in the water he has this baptism and this emotional thing happens to him and he says ‘sorry’ to his daughter. And I would love it if she had no remorse. But she…

BM: Looking at her father in the water there is this thing that goes across her eyes, like ‘I want to get him out of that water,’ or ‘I want to join him.’

The personal dynamics of The East are very free and very open both socially and otherwise.

M: It’s interesting that people seem really shocked by the group bathing scene. I saw this video game the other day where people were being dismembered, there’s blood, ripping out spinal cords and no one is flinching…

ZB: That’s where you got ‘ripping out spinal cords?’ You were talking about that the other day and I was like, ‘Where did you get that from?’

BM: In movies too! There is so much violence and nobody flinches. And then this scene where people are just in the water touching each other; it’s such a thing about our time that we have become so afraid of intimacy and contact and looking each other in the eye and real connection, instead retreating to the Twitter and Facebook portals where it’s like, ‘I’ll talk to you, but only from over here.’

Have you guys seen Disconnect yet?

ZB: No, we want to. That’s Alex’s (Skarsgard) movie.

The point is that we are more connected than ever but disconnected, hiding behind these guises and putting so much of ourselves into profiles, personas and people online that we don’t see people in our ‘real’ lives and we can’t see ourselves accurately anymore.

BM: That was one of the most amazing things about the summer we spent traveling with some of these groups, was that they were so connected to each other. At first it was weird to sleep ten people to a room and have no private space and wake up one morning and see someone else in your sneakers. But at some point it crossed over and you were so glad to have a community and a tribe and stop thinking about yourself. It was just like this amazing thing of letting go of ‘you,’ with no mirrors, so you even forget what you look like. ‘You’ dissolves into a group, which can sound like Stockholm Syndrome…

ZB: ..or new age-y or cult-y. But I don’t think The East is a cult because a cult has a spiritual reference to it. I think Sound of My Voice is a cult, but I think The East is much more of a political thing. They do weird things, like the (eating soup with straightjackets) scene, which no anarchist group does, but that was from our imaginations.

BM: But they do things that are about bonding and connecting. That scene is about pushing it to an extreme, but it’s about thinking about each other rather than yourself.

ZB: 100%. And that’s what we felt and were trying to figure it out in a movie so that the audience would feel it.

So let me get your thoughts on kind of a macro-industry topic, which is about women in American film, specifically women’s roles. I’m very thankful for Jessica Chastain and yourself, as I think the two of you are really energizing the movies at the moment as a new guard of young actresses. But I also read an interview with you where you mentioned that you came to a realization that you would have to write interesting women and then cast yourself in the movies if you wanted to do the type of work you want to do.

BM: Yeah, I think for sure when I first started acting I was shocked because you see movies all of your life with men and women in them, and it’s not really until you try to act in them that you realize you are always going to be in a submissive position, passive; that you ask a lot of questions but you never say anything—that your job is to sort of ‘serve up’ the scene so that the male protagonist can say his piece. It took me awhile to realize that from an acting perspective, and then I started writing. I got very lucky that both Mike (Cahill, Another Earth) and Zal are interested in strong women, and interested in women and talking about women. When we sit down to write, we do talk about trying to write a girl who acts with agency and doesn’t have all of this stuff happening to her but is somehow driving the action of the film. It’s a hard thing to do and you do find yourself putting her in passive positions because it is what you have been raised on; it’s how you have been raised. So we think about it and talk about it out loud all of the time. Even as we start to write something new, we still have to remind ourselves because you forget. It’s something of which you have to always be cognizant.

ZB: Or the inverse. Can you imagine if Sarah were written as a guy—the movie would just be different. We would have all of the sexual elements, like him being handsome… It is just totally different. You don’t want to get into a space where you imagine him as a guy and then all of a sudden all of these possibilities show up and then you just switch it back to a girl, because then women are…

BM: …being strong in the way that men are strong. What is a woman who is strong in the way that women are strong? We don’t know what that actually looks like because women haven’t been writing…

ZB: …Or if they have been writing, like Thelma and Louise, Ridley Scott then directs it so it creates a great balance, and that was very digestible and people were ready for it at the time. But imagine if Kathryn Bigelow had directed it? Or someone even more feminine?

BM: And we seem to have gone backwards from that time. I was reading something recently where the interviewer was asking the young girl if she was a feminist, and the girl was like, ‘Oh no, no, no. I’m not a feminist.’ It was as if the word has somehow gotten dirty.

ZB: Yeah, but people who are not feminists or environmentalists are on crack. Because those two things—you have got to be an environmentalist. You have got to care about the environment that we live in.

BM: And you have got to care about women and the idea that women are not just oppressed in this culture, less obviously, but just all over the world.

ZB: We were coming back from Sound of My Voice and my eighteen-year-old cousin was with a girl who was a freshman or sophomore at Barnard, and she was like, ‘What’s weird is all of these feminists and all of these feminist classes.’ I was like, ‘Just wait until you get older.’

BM: I was like, ‘Girl, get into that and take those classes, because when you leave the bubble of college you will be shocked at how the world actually works.’

ZB: And how the world is going to treat you.

One of the many complexities in The East is that we have to ask ourselves if the ends justify the means. Meaning, if we agree with the organization’s ultimate goal, how do we then feel about the steps they take? It makes you question means and ends.

BM: I think where I fall is that I tend to think the means cannot justify an end. But that is because of how I have started to live my life. I used to think that what you did for a living was separate from who you are, but it is not. The thing you do daily is who you are. So I am very preoccupied with the idea that if you do a certain series of actions that become an end, along the way you will become that person. Even if your end is noble, you cannot avoid the way you got there.

ZB: Or vice versa. I think that doing the right thing is important even if the end result is wrong. I really believe that.

What is the best part about your jobs?

ZB: Is it cheesy if I say this? The idea of what you just said about how Sarah leaves the political and religious aside and actually touches other people and people become human. I had never thought of it that way. I watched the second to the last episode of Enlightened the other day and that happens on that show, and I didn’t realize that we had done it to. It’s neat to make something and then have it meet the world. It gives us such great pleasure that we get to talk and connect with you.

Special thanks to Brit Marling and Zal Batmanglij for this interview