In her 2020 Sundance-winning The Forty Year-Old Version, New York playwright Radha Blank wrote and directed a close-to-reality self-portrait of a Black writer and artist in a state of continual invention. Her dilemma? The Broadway purse strings, held by affluent, liberal white producers and audiences, had less interest in her authentic (and autobiographical) new play about a Black, middle class couple and more interest in having her create a “Harriet Tubman musical,” or at least infuse a bit of Harlem gang violence into her decidedly less sensational marital drama. The picture was a vital character study of an urban artist in a state of radical reinvention and an incisively barbed view of the tension between truth and commerce for diverse artists required to be reductively accessible to a populous more comfortable embracing stereotypes.

This authenticity vs. marketability DNA is the satiric catalyst for Cord Jefferson’s dynamic new comedy-drama American Fiction, which pulls no punches in its take-down of patronizing Black stories that liberal white audiences embrace as “brave” at the expense of artists (and people) of color with a myriad of life experiences outside of safely palatable cliches.

Such marginalizing consumer dictates don’t sit well with Thelonious “Monk” Ellison (Jeffrey Wright), a formerly successful author whose newest book can’t find a publisher because it doesn’t suit the Black experience the book buying world has embraced. Given that Monk himself is a Black author, what experience exactly?

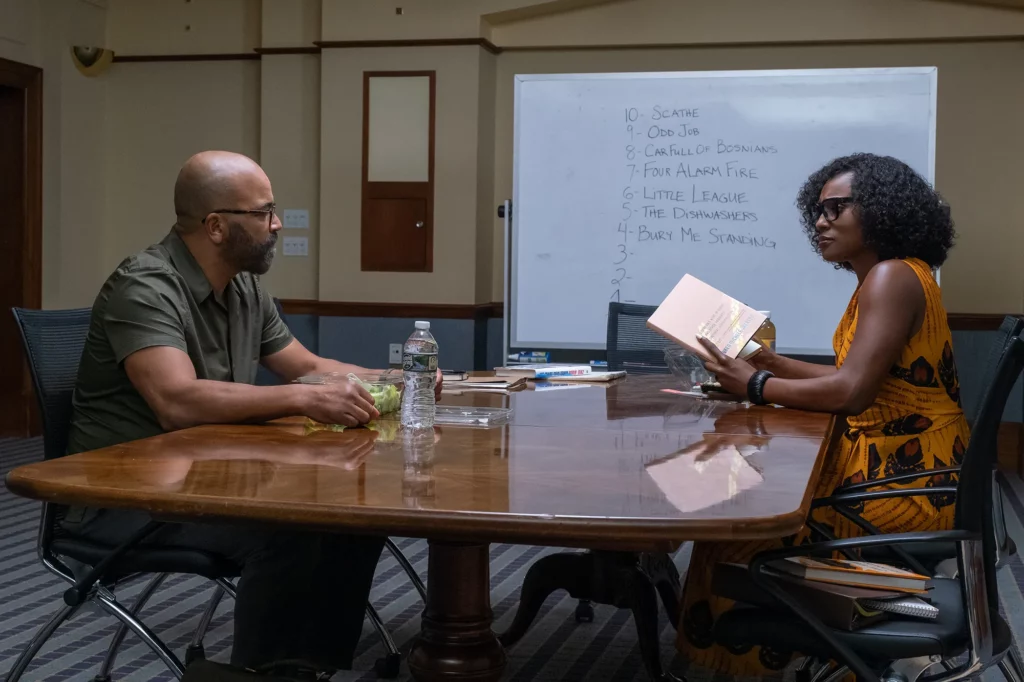

Enter Sintara Golden (Issa Rae), whose bestselling novel We’s Lives in Da Ghetto is heralded a literary masterpiece, at least by white editors, publishing houses and consumers. Monk, he believes, sees Golden clearly: well-educated, of literary pedigree and whose own experiences couldn’t be further from the cynically pandering “Black trauma porn” she writes. Yet what sells, sells.

We first meet Monk as a California college professor chided by a white female student, herself triggered by the “N” word in a heated exchange resulting in the frustrated scribe taking a leave of absence. As an author, he just can’t seem to close a new book deal despite the support of his longtime editor (Jon Ortiz), who laments that Monk’s books, including his latest, titled The Persians, are perceived as “not Black enough.” Come again?

On the personal side, Monk makes a trip back to the Boston area for an impromptu reunion at the seaside family home owned by his aging mother Agnes (Leslie Uggams) and M.D. sister Lisa (Tracee Ellis Ross), and is soon joined by his brother Cliff, a Tucson plastic surgeon (a sensational Sterling K. Brown) whose wife and children have left him after discovering he’s gay. Mom is suffering from dementia and will soon need full-time care, and brothers are at severe odds. Kindly neighbor Coraline (a warm Erika Alexander) presents a romantic prospect for the acerbic writer, who in a fit of venting anxiety pens a stereotypical urban thug melodrama intended for the circular file but which inadvertently gets shopped to publishers.

You can guess what happens next—a big New York publisher (Miriam Shor, in a very funny cameo) seizes on the manuscript, titled My Pafology, and the pseudonym-written, purple expose becomes a high-six-figures capturing deal and runaway bestseller. The problem? Monk despises it, and is increasingly called upon to play the part of its author, a purported, formerly incarcerated killer and fugitive on the run from the feds, and one who conveniently can’t be seen publicly. Wright has an absolute ball personifying this urban fugitive persona; the further his Monk pushes the ruse (even persuading the publisher to rename the book F**k) the more the market responds. A few quagmires—Hollywood comes calling in the form of a hotshot, street cred producer (Adam Brody) and a tony literary contest invites Monk to join its jury. Guess which book is high on the list for the big prize?

With American Fiction, Jefferson, a first-time filmmaker, has made the definition of an auspicious debut, one that incorporates media satire, high comedy, compelling family drama and provocative questions about race and culture. Across the film, he shrewdly presents Monk and his family as antithetical to the harmful stereotypes he rails against, and the domestic complexity, particularly in the interactions between Wright and Brown as well as those featuring the winning Alexander, are amongst the most enjoyably well-written and acted in an American film this year. These maladjusted, long-standing family dynamics are effectively integrated with the broader consumer satire, right to a moving scene between brothers in which Brown, for my money the best supporting actor this year, says just the right thing at the right moment.

Throughout this acidic, pointed take-down of how harmful stereotypes sell cultures short and contribute greatly to diminishing personal experiences and complexities, Wright, the longtime award-winning actor whose performance in Julian Schnabel’s 1996 Basquiat launched his movie career in scores of films, television and theater since, is handed perhaps the smartest American character (this side of J. Robert Oppenheimer) onscreen this year.

His Monk, whose professional and cultural disillusionment registers as caustic scorn, is in the actor’s hands alternately indignant and defeated, Wright etching every comic zinger beautifully in rooted cynicism. By the picture’s end, Monk will come to understand the notion of selling out, which is more complicated than suspected, and the compromises an artist faces even in success. How realistic is it, the film asks, to expect any one artist (including Sinatra Golden) to represent the be-all, end-all of a culture’s wide swath of history and experience?

First-timer Jefferson, who also wrote the screenplay, has found an impeccable sweet spot that can be thrilling to take in, every scene loaded with piquant cultural observation or family revelation; he builds the picture to a final act where a trip to Hollywood demonstrate the struggle of an artist railing not merely against the literary world’s reductive racial simplicity but the entertainment business at large obscuring truth by bigger-is-better moviemaking. The final shot is superb, at once an ironic juxtaposition and bitter truth.

3 1/2 stars