In their new picture Hilma, Lena Olin and Tora Hallström play cross-generational versions of pioneering Swedish abstract artist and mystic Hilma af Klint, a quintessential woman out of time whose groundbreaking works were dismissed by the early 20th century patriarchal artistic establishment. A modern, gay, fiercely independent outsider artist, Klint’s posthumous renown came too late for her own success but ultimately redefined public narratives about the origins of abstract art. Today, her revered style and canon can be seen around the world from New York’s Museum of Modern Art and The Guggenheim to the artist’s Stockholm studio.

In a seamless acting amalgam, the real-life mother-daughter acting duo—directed here by husband and father Lasse Hallström—essays the decades-spanning personal trials, professional setbacks and spiritual evolution of a complicated creator. A film family affair writ large onscreen between the estimable Olin and newcomer Hallström, who carries the film, Hilma delivers an illuminating art history character study of a largely unheralded creative genius.

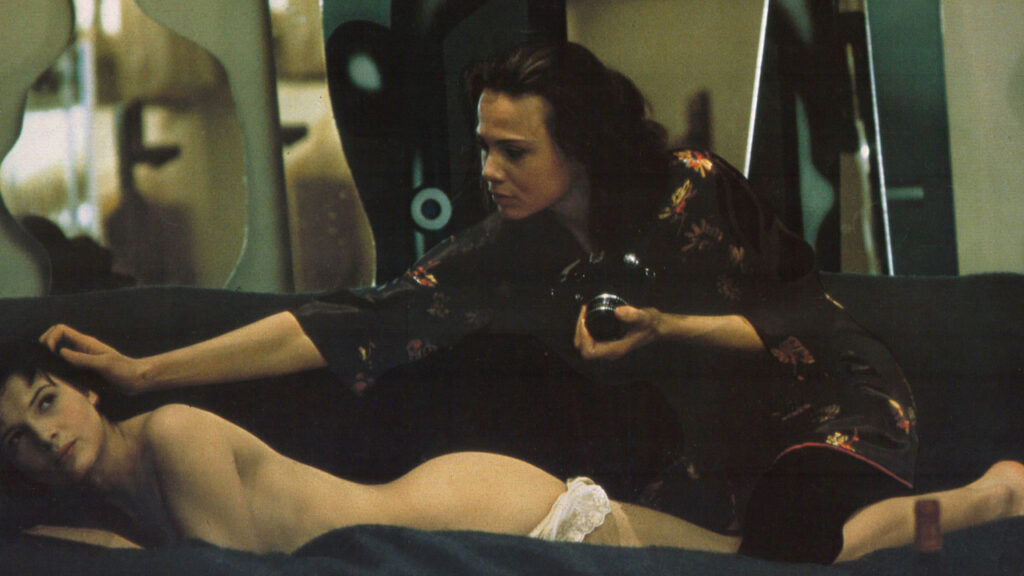

Olin, the Swedish actress and Ingmar Bergman protege turned dynamic movie star, headlined the Stockholm stage and appeared in Bergman’s Fanny and Alexander and After the Rehearsal before filmmaker Philip Kaufman cast her in his spellbinding 1988 adaptation of Milan Kundera’s “unfilmable” novel The Unbearable Lightness of Being. Playing a sensual, independent artist entangled in a free-spirited roundelay with Daniel Day-Lewis and Juliette Binoche during Czechoslovakia’s 1968’s Prague Spring, Olin instantly wowed international critics and audiences, earning a deserved Golden Globe nomination.

Hollywood called, as it does, Olin quickly establishing a reputation for confident, large-scale movie glamour. It didn’t hurt that she could play it all with aplomb: romantic melodrama opposite Robert Redford in Sydney Pollack’s Havana; black-hearted femme fatale noir with Gary Oldman in Peter Medak’s Romeo is Bleeding; a tormented Holocaust survivor in her Oscar-nominated turn in Paul Mazursky’s Enemies, A Love Story; a compassionate therapist guiding Richard Gere in Mike Figgis’ Mr. Jones; a boundary-crossing attorney in Sidney Lumet’s Night Falls on Manhattan; and an abused wife redeemed by personal agency in Hallström’s Best Picture-nominated Chocolat. And still, there is much more, including an Emmy-nominated turn as a KGB agent and “the most dangerous woman in the world” on television’s Alias.

In Hilma, Olin’s reflective, aged painter stands in support of Hallström’s vigorous portrait of the artist as a young woman. The twenty-eight-year-old actress, who pursued a career in finance until COVID-era soul-searching led her out of the business world and into the family vocation, shines in her first major role. Courtesy of her father’s ambitious screenplay, she dexterously navigates a spectrum of experiences in close-up: artistic flowering, romantic passion, familial rejection and an intense drive toward creation. Such an agenda would be daunting for any young actress, especially one with the added pressure to impress her discerning parents. But the star is confidant, unstudied and naturalistic, informing the picture with contemporary directness.

The pair greets me as I exit the elevator to the lobby of Chicago’s tony Langham Hotel, the regal Olin offering her signature, screen-sized flash of a smile and husky vocal gravitas, dual reminders of why she became an indelible movie star. While such glossy Hollywood pictures that gave her a 90s hot streak may be rare at today’s multiplex, the star remains larger-than-life, confirming the famous adage that only the pictures have gotten smaller. The star is as big as ever.

During our discussion, the Olin and Hallström dynamic was one of mother and daughter as well as of acting contemporaries, often speaking directly to each other about on-set observations, collaboration in bringing Hilma to life and personal familial anecdotes, including their thoughts on growing up in famous entertainment households. We also took a deep dive into the heart work integral to great acting, a sort of divine alchemy that occurs in the best moments, and we considered cinema’s value to culture and humanity. Of course, we examined a handful of my favorite Olin career milestones. It was quite a time.

Lee Shoquist: In 1988 I was a teen living in a small, far out country town. I must have driven about fifty miles to the nearest city to see The Unbearable Lightness of Being—and did so three times. I believe it was my first arthouse experience.

Lena Olin: Oh my god, that’s so lovely.

I remember running into you about 25 years ago on Madison Avenue in New York and saying to myself, ‘I should tell her how much I enjoyed that film.’

LO: Really? You should have talked to me and told me! Those interactions are so sweet. My heart always starts beating and it’s so, so lovely.

I wanted to wait for a professional setting. I didn’t know it would take twenty-five years! Your new film, Hilma, is very interesting and quite beautiful. Tora, this is also a big film for you. You’re holding almost every scene in your first major role. Tell me a little bit about playing this character and taking on that challenge.

Tora Hallström: Yes. I was working in tech in San Francisco. During the pandemic I moved home and was living alone with my parents.

So you weren’t acting?

TH: No, I wasn’t. I’d always been drawn to creative stuff growing up, and then I went to college and got sucked into the whole finance route and it felt safe, and I wanted to prove that I could do something that my parents couldn’t help me with. When the pandemic hit I had just turned 25 and was kind of just sitting and meditating, thinking about my life. And then I realized that I had just shut that side of myself down. At the same time my dad had done a version of the Hilma script, so we started workshopping it together and it just hit me right away. While reading it I was just melting.

I was having these thoughts about wanting to try (acting) and was tracing my life and the threads all led to this. We were workshopping the script and I thought it would be pretty awesome if it did happen and they accepted me being in it without being proven. Thinking that Hilma wouldn’t happen I applied to acting school. And then the Swedish producers came in and said, ‘Let’s do it.’ So I was just thrown into it before I even got the chance to go to acting school. Now I’m in acting school.

Hilma is a great character. In a sense, she almost seems modern in terms of her struggle against the attitudes of the men in her worlds. I felt that you and co-star Catherine Chalk were quite contemporary together. Sometimes in period pieces there is a little bit of a different style of performing. But here there was something very modern.

LO: Yes!

TH: Yeah, I am so glad you felt that way. I wanted people to see that and not a stuffy period. Because we were in corsets, we did not want to suppress the humanity and darkness and lightness and all of it. Hilma was such a modern woman in the wrong time, and we hoped to make it clear that she’s someone women watching today could recognize themselves in and see that she is cool and funny and all those things that are beautiful and make women complicated creatures.

LO: I’m just going to quickly say that I came to the set before I started shooting my part as older Hilma, and when I watched the monitor I was like, ‘They’re breaking the costumes,’ and I didn’t mean breaking them, but because it is very constricting the costume can take over and that easily happens. But when I watched them they were breaking it all, which was so refreshing!

I discovered sides of myself that I think I have been suppressing my whole life.

Tora Hallström

Lena, you were at 31,000 feet when you got the idea for this film.

LO: Yes! I was flying from the West Coast to East Hampton where I was going to begin shooting a film called The Artist’s Wife with Bruce Dern. And when I was on the flight, I watched Personal Shopper with Kristin Stewart, in which she was looking for her dead brother and talked about a Swedish painter, Hilma Klint, whom she claimed was in contact with the other side. And I thought, ‘Is that a fictional character? Because I’ve never heard of her.’ Tom Dolby, who was directing the film, was very into art. And I said, ‘Do you know of Hilma Klint, the Swedish painter?’ And he said, ‘No, but I have heard the name, so she’s real.’ I mentioned that to Lasse, who was with me in East Hampton and writing this script about UFOs. He looked her up and from that moment became completely obsessed with her. We went to Sweden and got to know her relatives and traveled to the places where she had been, and then went to Berlin where Julia Voss was writing this big biography about her life. From then on it’s been Hilma.

The two of you are together, playing the same character. Is there work you did around that?

LO: Yes.

How do you coordinate that? Is it like, ‘You do this, I’ll do this, we should both do this,’ or not that didactic? How’s the work around that?

TH: Yes, totally. I mean, it started with us workshopping the script with my dad, who had written the first draft and then we came in and were very annoying and pushy (laughter). And so we had all these ideas and were aligned about how we wanted her to be complicated and flawed and while she was a genius and well respected, that she could be difficult and have her faults too and be funny and bold and modern as we were talking about. We were immediately aligned on the little things we wanted her to do and so that just naturally came together. On Sundays we would have a routine where, all together in a hotel room, we would go through the scenes for the week. And we would talk about little things, like the fact that she eats when she’s stressed. That’s something that we both identify with—we are always hungry!

LO: Yeah! Little things like that. Because we had read about her and how the spirits had asked them not to eat too much meat; they had all these restrictions. And I think that was her way of getting into her soul and her spirit. And I believe a lot of people can relate to that. We are both obsessed with food, and I think that is very relatable (laughs). And when the wonderful actor who plays her nephew has that scene where he tells her, ‘Nobody understands what you’re doing,’ we thought food—when you’re devastated and are just like, ‘Okay, I’m going to bring it all out!’ That made sense to all of us.

Tora, you are in close-up through much of the film. There is something about the way you hold the camera; you have purpose. For example, the scene where at the funeral where you are pushing your way through and just say ‘thank you.’ I felt like you knew what you were doing in each scene, and not just those involving the creation of art. I wonder if you have any thoughts on being front and center of this movie, so close.

TH: Yes. I thought I would be really nervous and stressed out with the camera because I’d never really experienced that, but it felt like it was a close friend. It’s like when you have something on your mind that you are emotional about and you call your mom on FaceTime and then break down because it’s someone who sees you so intimately. I felt that immediately with the camera, which was a surprise to me. I discovered sides of myself that I think I have been suppressing my whole life and so all this came out. You can’t help but emote when it is there because it is listening to you so intimately.

When the camera is on you’re trusting that ‘If I take this straight from my heart and if it’s funny or moving or uncomfortable or shameful or sexy—whatever it is—it goes from my heart,’ then people are going to receive it in their hearts, you know?

Lena Olin

Lena, there’s a discussion in the movie about working from the heart versus the head; about art that comes from the personal. Do you think about that when you’re actually doing a job? Is it different depending on the film, for example when you are on Alias (laughter) versus, say, Romeo is Bleeding? ‘This one I’m working from here, and this one I’m working from here’—is that a conscious thing?

LO: Yes! Yes. I think absolutely so. I think it’s always from the heart and it’s always a personal message to the audience. In this case, Hilma trusted us. She trusted, ‘I’m painting for the future. I understand that no one will understand me now. But I’m doing this for the future.’ It’s for the people. And the name of her exhibition at Guggenheim was Hilma of Klint: Paintings for the Future. And I think when the camera is on and you’re working, you’re trusting that ‘If I take this straight from my heart and if it’s funny or moving or uncomfortable or shameful or sexy—whatever it is—it goes from my heart,’ then people are going to receive it in their hearts, you know? That’s the sort of faith that I have. And I think on the intellectual-type job, I’m insane! Tora, you said, ‘I didn’t understand how insanely intensively you work before a film.’ You do all the thinking you can and then once you get to set you just have to drop everything. You have to be led by your heart.

It’s so amazing because I agree with you. When I watched Tora as she worked- it takes such bravery to be able to be that honest with the camera and not to (perform like), ‘I can show you this and I can show you that.’ To be that completely authentic and honest is what I’m interested in watching. It is like when you watch kids playing and they have planned that ‘We’re going to play this and I’m going be that.’ But when they don’t know that you’re watching them it is fascinating and so authentic.

This reminds me of the scene in The Unbearable Lightness of Being where you’re photographing Juliette Binoche. Her character is initially very uncomfortable being open for the camera, but over the course of that extended sequence she is able to authentically communicate her essence and the camera captures it.

LO: Yeah, yeah! Yeah, exactly. That kind of honesty. It’s brave to take all the pretend away and just be there in the situation. But that takes a lot of preparation too. It’s so fun. (To Tora) I was disappointed that we never had scenes together because I love to work with actors that way. It’s so incredible. I just did a film with Anthony Hopkins. He does that to a T. You may be like, ‘How am I going to solve this? Because it’s like, I have the bag, I’m getting on the bus and what the hell am I going to do? Because I’m saying goodbye and it’s complicated.’ And you look into his eyes, and it just goes away. Because he lives in the moment. And that’s all you can ask for. But that takes a lot of courage and a lot of preparation, or you might be a child actor who is so unaware of everything. When you’re working with a kid you look into their eyes and suddenly they do something and you just have to react, you know?

And it’s a little bit throwing when you work with actors that are the opposite when they come in and play this and that and (broadly theatrically) ‘Hello, Mrs. So-and-So!’ I almost want to look at the director and ask, ‘What am I supposed to do? Should I also (laughter)? Or should I stay in the situation ask the waiter in the scene to help me because this man has obviously gone insane (laughter)?’

I was recently considering Cate Blanchett in Tar. There’s some kind of alchemy in the performance that is almost magical. I don’t know if it’s channeling something or what exactly it is, but there’s a discussion in Hilma about being guided by something spiritual, perhaps to a state of creative possession. I wonder if that is what great actors do and if there’s something else in that moment that is coming from somewhere else. I don’t know. But it’s great to watch.

LO: I believe that’s absolutely true. That when you- those lucky moments when it’s not that you are presenting something, but you open up your heart, and you’re super deep into your heart, and then it comes. You might be onstage or in front of the camera and you suddenly do things and it’s like, ‘Where did I get that from?’ And it’s that divine intervention. I think that’s what Hilma is trying to describe. She was so scientific, and because she was trying to understand what it was they had these names for all the spirits.

I think we feel that in the movie when she’s creating art through them. There’s a beautiful sequence that employs animation as well as the colors swirl onscreen.

LO: Yes. And there was a funny scene that I don’t think made it into the movie, because it was such a long take, when because of their names one of the other girls comments, ‘Are these spirits all men?’ They want to categorize it, but I think what she’s trying to describe is that when it happens that is true creative genius.

Can you share a bit about your dynamic as a family making this film? Tora, would the film have been different for you if it had just been another director in Hollywood who hired you to do the role?

TH: (Laughter) Yeah, it was such a big jump for me to even go into this career, so I didn’t know if I was any good and I think no one else knew either. I was going to try my best, but I did not know if it was going to go well. But my dad just had such faith in me, and he holds me to a very high standard so he’s hard on me (to Olin) as are you. But I knew that if it were bad he would tell me. It was so nice being able to just let myself go as far as I wanted to and know that he would be honest with me, versus another director who might have said, ‘Yeah, okay, good job.’ And that would have been awful. I would have gone home and that would have been the end of my career. So there was a comfort in being able to just let go and know that there was someone behind the camera who had my back.

My dad had such faith in me, and he holds me to a very high standard. It was so nice being able to just let myself go as far as I wanted to and know that he would be honest with me.

Tora Hallström

LO: And in your career you have to look for directors that give you that comfort that you really trust that they’re going to push you when you need to be pushed or stop you when you need to be stopped, and that when they’re in the editing room they will pick the right moments. Obviously, it’s a great start to work with someone that you know so well and who has your best interests in mind. That is a dream situation and I’ve been lucky to work with a lot of directors that I really trust that way. That’s a blessing because if you have to think about it or pretend to trust them you can’t work, you know?

Lena, what about for you growing up in a theatrical family and also with famous parents? Was it the same sort of experience Tora was just describing?

LO: Yeah! I don’t know anything else. And I remember when I was a kid growing up I was so attracted to the ‘normal’ family. My family was so funny and so loud, and all of their friends were big stars and actors. So people were always loud, funny and crazy, and I was so attracted to normal—like a little boring, where the dad comes home at the same time every night, and they have some pasta dish, and nobody talks much and they have bunk beds. I was so attracted to that normal life and normal people because I always felt that we were odd. I grew up in a very privileged area and we were different because we were ‘the actors’ and ‘the acting family.’ And we had a lot of tragedy in my family too, so that added on to being famous.

It’s interesting because I realized that we do we do that to our children too. Our son is very- when we’re in Sweden he is like, ‘I don’t want to be close to you guys. I hate it.’ (To Tora) But when you were little, if somebody came up and said something nice to me you would say, ‘Oh, that’s nice.’ But I think it’s in your blood because you’ve been exposed to it since you were so little. You were two or three months old when I shot Night Falls on Manhattan for Sidney Lumet, and since then you’ve been either with me or Lasse on movie sets. So you have sat by the monitor and watched more than anyone I know (laughs). There is a funny picture from Casanova when you were maybe ten or eleven, and you are sitting next to Lasse and you don’t love what you are seeing on the monitor. You can see that you are a little critical (laughs).

You both grew up in similar artistic families. Yet Tora, you pursued finance and Lena, you nearly became a doctor before both of you came back around to acting.

LO: Yeah, yeah (laughs). I think because I was good in school, and I thought it was so obvious that ‘This cute girl is probably going to be an actress,’ so I wanted to (study medicine). But I did not succeed because I fainted and had a lot of problems with medical situations. (To Tora) I think you had talent for the academic side and so for you it was easier. I didn’t do that enough, and I think it’s healthy to have a spine going into this job. I think that helps you a lot, because I’m like, my God, ‘She’s just cruising here in such an amazing way.’ But I think it helped that you had a career that was very impressive in another field with the colleges and business that we don’t know much about (laughs)! People are like, ‘Do you realize what she’s doing?’ Yeah, but neither me nor Lasse understand that. So we loved it when she danced and sang and things like that (laughs).

TH: They were so disappointed in me when I got a job (laughs)!

LO: And Tora would say, ‘My friends’ parents are applauding so much and asking every day about the things I do.’ And we were like, ‘Oh, good! What is that really (laughter)?

Tora, what is the best part about your job as an actress?

TH: I get to play for work. It is so odd now because most of my friends from college still work in finance and other than my classmates I actually have no friends in New York that are actors. My friends sometimes have conversations where they’re like, ‘I don’t think I am ever going to like work. Work is something you go to and you don’t like it.’ I think once you’ve tasted what it feels like to love your job you can’t go back. It is hard work also. Acting is not just sitting in a spa chair getting a facial all day. It’s really hard. It’s hard hours. Still, I hated the weekend because I just wanted to be back on set. And to spend most of your time doing something and love it that way… I can’t ever go back which is scary because this is a hard business.

I think you’ll be going back to acting after this, not finance.

TH: That is what I’m hoping for!

I saw Danny (Day-Lewis) not long ago and he is not acting anymore. But I understand. The experience takes a lot. I think that Daniel’s reasoning is like, ‘I’ve done so much. It’s so painful to go through it. So I am just going to live life.’

Lena Olin

Lena, can you talk about The Unbearable Lightness of Being? Anything you can share?

LO: Yeah! That it was such an extraordinary experience and I’m so blessed to have gotten that opportunity because it led to me working here and internationally, which is amazing. I just made a film in Sweden with a very big and celebrated actor. I was like, ‘God, I’m so lucky to have that international career.’ And that was the role where I was like, ‘This is a big thing.’ And it happened. I wasn’t looking for it.

I was doing a play at the Royal Dramatic Theatre, where I had been working for a while. I was doing some movies in Sweden. But I got the opportunity through a fluke because Saul Zaentz and Phil Kaufman came to Stockholm for the anniversary of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, and they saw me and wanted to meet with me. And then I got the part and the whole thing was just happening without me trying. And that’s what gave me the golden ticket—like the chocolate factory ticket! And that’s amazing.

I immediately bonded, so quickly, with Daniel (Day-Lewis). I saw Danny not long ago and he is not acting anymore. I was like, ‘Why not?’ But I understand. The experience takes a lot. I think that Daniel’s reasoning is like, ‘I’ve gotten so much. I’ve done so much. It’s so painful to go through it. So I am just going to live life.’ It was such an extraordinary experience with Philip and Sven Nykvist, the greatest cinematographer, whom I had known since I was a kid. So that helped. And it opened up these doors. Had I known how amazing it was I would have been knocking on those doors! But I didn’t know until I magically walked right in.

I think it’s the film that pushed me into film school.

LO: Wow! That’s amazing. That is so cool.

I remember many of those scenes perfectly, for example, when Derek de Lint comes to your apartment and confesses that he’s left his wife for you and then your reaction.

LO: Yeah, I’m a little bit like, ah, ‘I wasn’t that serious!’

You get the shot over his shoulder, yeah. The also the moment where you’re in the restaurant with that music playing and you say to the server, ‘How can you eat good food and listen to shit?’ Even today when I am in a restaurant I still always think of that scene.

LO: I do too (laughter)! I say that sometimes too! Because I think at that point- first I was a drama student, I didn’t have the money to go to restaurants, and then I was always working at the theater. I’d go out to clubs after work. But now that I go to a restaurant, it’s a nice morning maybe, and there is this completely meaningless music (hums trivial music)!

Or television.

LO: Yeah. And I’m always thinking of my character that goes to a restaurant and says, ‘Can you turn that darn music off? Why is it on?’ And so I do too!

How about Mona DeMarco?

LO: Oh, I love her! I love her so much. (To Tora) That’s a crazy film that I did! Tora watches my films and she’s like, ‘It’s kind of awkward to watch you, mom…’

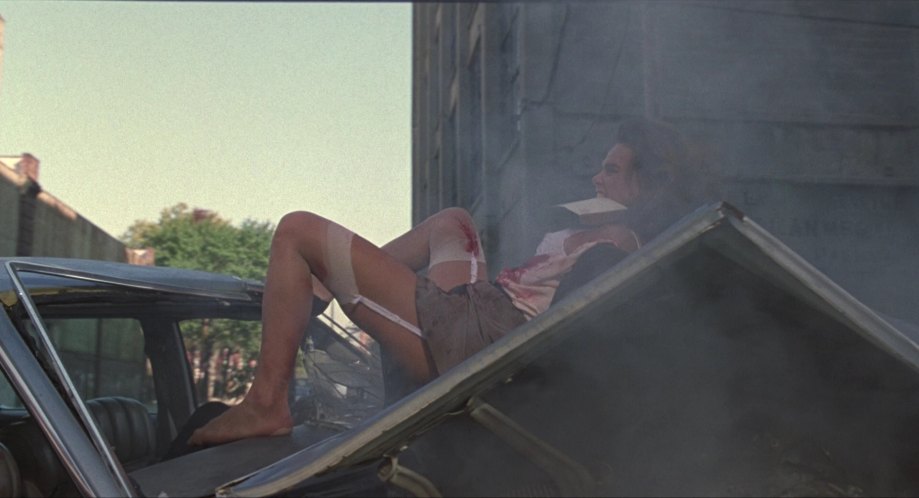

She’s never seen Romeo is Bleeding and witnessed you kicking that windshield out of the car?

LO: No, no! But I remember (the crew) screamed at the monitor when I did that, because that wasn’t really planned. In the scene, I am handcuffed and have been left in the car and I am supposed to get out. The plan was for a stunt double. They had that sugar glass that’s not dangerous to go through obviously or I would have killed myself. But I knew it was sugar glass and that the stunt girl was prepared to go in afterwards and kick that glass, and then I was supposed to run. And I was a very athletic kid so I felt, ‘I can do this!’ So I kicked out the window, got out of the car and ran down the street, and I was wearing those high-heeled shoes and so I kicked the shoe. That’s when I heard them scream at the monitor! It was so fun.

TH: Were you not supposed to kick the shoes off?

LO: No! It was just one of those moments. I was just like, ‘I need to get away from the cops and I can’t run as fast as I need to.’ This woman was a criminal. But it was so fun. It was so fun to shoot with Gary Oldman, who is so much fun to work with. Yeah, that was a fun one.

Working with Bergman, every little move of an eyebrow was so specific. With Paul (Mazursky) it was liberating to work with someone who was like, ‘It doesn’t matter. Just do it!’

Lena Olin

What do you recall about your experience with Paul Mazursky, who directed your Oscar-nominated performance in Enemies, A Love Story?

LO: He is a dream. Was a dream. He is a dream. And he’s so playful and taught me a lot about moviemaking because I worked with Bergman and such serious people. He was very helpful because he would say, ‘Don’t take it so seriously. Fuck it, anyway! It’s just two minutes out of the movie.’ Working with Bergman, every little move of an eyebrow was so specific. But with Paul it was like, ‘Just do it!’ It was interesting and fun. It was a liberating way to work. Yet I don’t agree! I think every single freaking half nano-second of a movie is important and everything has to be a choice, even though it’s a divine choice. But it was helpful and liberating to work with someone who was like, ‘It doesn’t matter. Just do it!’

Tora, while making Hilma what did you most learn that you will take to your next film?

TH: I think one thing (my mom) always said to me was to surprise myself and surprise other people through that too. I think my most exciting moments of growth came from doing something totally out of the ordinary that I wouldn’t normally do. And sometimes it would come to me in the moment, like those spiritual things. It was trying things that made me uncomfortable to see what would happen to me and the other people. Those little spontaneous moments were so fun, and I grew so much from them. I’m hoping to do more of that.

Why do you think Hilma wasn’t appreciated in her time?

LO: I think it has to do with that she was a woman and from the north. I think she had trouble in her life with that family, which was very aristocratic and so conventional, and she was so unconventional. She was gay and artistic and didn’t want to marry a doctor and all of those things. So I think she had a lot of resistance from her family. And then she was a woman. I think had she been a man- because she made those little, small miniature paintings of everything she did and she gave them to (Rudolph) Steiner because she so badly wanted- she was like, ‘I know you’ve seen what I see. And you just have to admit it.’ And he wouldn’t because I think it was sort of a Salieri and Mozart relationship where he was like, ‘This woman is incredible. But I’m Rudolf Steiner. I’m the big Rudolf Steiner.’ But I think he showed (her work) to Kandinsky and Mondrian. And they just…

TH: That lines up exactly.

LO: Yeah. Because he went to Paris with her miniatures and they saw them and they were like, ‘That’s very cool.’ And then Kandinsky and Mondrian got praised.And that is what Julia Voss, who wrote the book, says in the documentary about Hilma: ‘Books need to be real. We need to be accurate.’ And this woman was the first to paint an abstract painting. And she never got recognition.

Speaking of women artists and recognition, it seems like a good moment in the film industry. Two women won Best Director over two years for making two great films. While we didn’t have any women nominated this year, do you feel that industry is shifting? That there’s more parity now between men and women?

LO: Yeah. Very much. It’s amazing. I think it’s a great time to be a clever, smart, brainy female actor and starting your career because we’re listened to so much more than when I started. And I think it’s #MeToo, actually, to certain people: ‘You don’t own the planet.’ And that is so incredibly inspiring and then also that people come to the movies to see it and celebrate it. Many people didn’t stand a chance before, which is a bit like the Hilma thing.

I didn’t quite understand some of the films I saw when I was very young, but they affected me so deeply. I understood that it was okay to have a soul.

Lena Olin

What do you think about the movies today? We have these huge movies we are told are supporting the industry. But adult-oriented films like many of those you made—a Chocolat, for example—have largely vanished from the commercial landscape. Do you feel hopeful about the future of movies for grown-ups?

LO: I certainly hope so and I think it’s heartbreaking- it was Scorsese I think that said, ‘I wouldn’t be who I am if it hadn’t been for cinema and watching the movies.’ I agree. I didn’t quite understand some of the films I saw when I was very young, like The Mirror by Tarkovsky, but they affected me so deeply. I understood that it was okay to have a soul. It was okay to think about things you don’t quite understand. It was okay to do so many things. I think it’s extremely important to young people—and to everyone—to watch movies and be affected in a different way than you are affected by the big action films, which need to have a place too. But I think it would be extremely sad if cinema died and it would have such a bad effect on people. It’s like, you would not stop reading, right? That would be awful.

But I am so hopeful when I see the younger generation responding to films like Hilma. We’ve had young people come up to Tora and say, ‘This is so important. We are so excited to watch it.’ I think there is a need. I think Hilma’s hope for the future is relevant. I think that we’re ready to embrace something more and it’s important. And then action films are entertainment. You have to eat candy too sometimes. But I think cinema is super important.

Tora, when you hear what your mom said about your generation and the value of cinema, do you feel that?

TH: Yeah. I love the shit that’s happening in my generation right now. I’m right on the cusp between Gen Z and Millennial. I’m on TikTok so I follow everything. I just love how people are so curious and it’s cool to be different and bring to light little niche hobbies, interests, thought patterns and spiritual things that people are engaging in. People who are different or have unique ideas are being celebrated on TikTok, which is really lovely. I think things like this will save it because people don’t want to just sit down and watch action movies all the time. They want to see something different.

You guys are creating a lot of content. I’m Generation X. Your contemporaries are far more sophisticated. We might try to do TikTok or try to make a little movie on our iPhones or something like that, but in this way we don’t quite have the content savvy of your generation, which seems to be effortlessly pushing the boundaries forward.

TH: Yeah, totally. I don’t make content myself, but I love- there may be stupid stuff on TikTok but much of it is insanely creative—musicians that are amazing at whatever instruments they play, singers, cooking and even short little stories that people tell that are funny or interesting. There are so many cool things that are happening there. It is definitely going to look different in the future for cinema and artistic expression, but I feel hopeful it is headed in a good direction.

LO: I need to start watching TikTok. Tora is a dancer too, so I am only on TikTok and just following you because if you put up a dance I will go, ‘Oh, that’s interesting.’

Lasse and I exposed Tora to so many difficult movies when she was younger, because her older brother was really into it and watched all of Scorsese’s movies when he was 11. It probably was not appropriate! But Tora was a very sensitive child. Lasse and I are Academy members and on Christmas breaks we used to put everyone down in the basement and watch the Academy films. I remember once I turned to see Tora in tears and I thought it was probably not a good idea for her. (To Tora) So you became, like, ‘I only want to watch fun romantic comedies. I don’t want to watch any more of this!’ But I think you had a breakthrough quite late with Black Swan. I had met (director) Darren Aronofsky and I said to you, ‘I watched it and maybe you should too because you’re a dancer.’ And I remember you called me and cried, and you made me cry, saying that the film had such an impact on you. You loved it. And that was the first time you were ready to watch the kind of movies that you had been overly exposed to earlier.

TH: Yes. That movie affected me so deeply that for weeks after I would be randomly crying. It was like I lived the movie, which I think was a good sign that I should be an actor (laughter) because I was just throwing myself into it as if I were in the movie. So I had a long phase where I couldn’t even go there. And then I started watching good films again because I had more of a developed brain, I guess, where I could learn to let go afterwards (laughter).

I remember being very young and watching Scorsese, Paul Schrader, John Cassavetes and Robert Altman, all of those guys when I was about 13.

LO: Yeah! That’s like (our son) Auguste! And we would be like, ‘Is this okay?’ But he just wanted to direct and that’s his passion. I think some kids can take it and that’s probably a director. And some kids get too affected and that’s probably an actor.

Thank you so much for making the time for me today. We’re very happy to have you here in Chicago.

LO: Oh, really nice to meet you! Thanks very much. Chicago is such a cool place. It’s very film oriented.

Tora, I very much enjoyed the film, and you did a lovely job.

TH: Thank you.

Well, you both did!

LO: (Laughs) Thank you!

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Hilma is currently playing at Manhattan’s Quad Cinema.