According to a recent New York Times calculation, the per prisoner cost of Guantanamo Bay detention is approximately $13 million—a hefty sum for the thirty-nine existing detainees from more than fifty nationalities, the majority from the Middle East. And while the debate over closing the prisoner outpost, fueled by public record of torture, unfair trials and otherwise barbarous treatment, has survived decades of controversy across multiple administrations with no closure in sight.

The right to habeas corpus is at the center of The Mauritanian, a gripping new picture, or perhaps case study, of one such prisoner, Mohamedou Ould Salhi, imprisoned at Guantanamo directly after 9/11 and held for seven years without being charged, and without any evidence to support allegation that he recruited terrorists other than one who spent a single, coincidental night on Slahi’s couch.

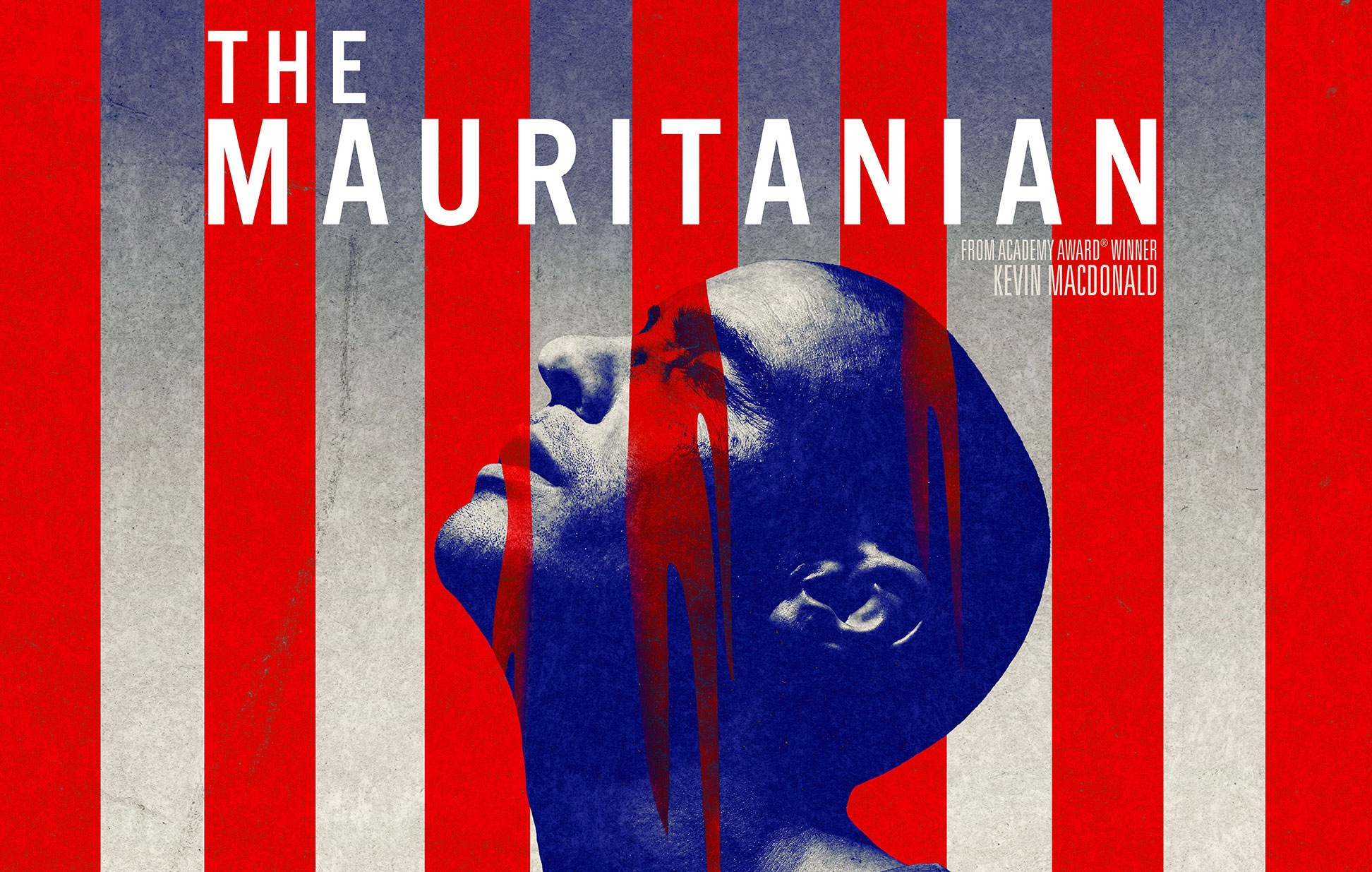

Salhi eventually wrote a (heavily redacted and later restored) best-selling 2015 memoir, Guantanamo Diaries, while incarcerated, and his story is the subject of director Kevin McDonald’s new picture The Mauritanian, an often powerful drama about the horrific goings on Slahi endured inside the lockup, and the struggles of the American attorney who fought, for years, to get her client a fair trial. Before his 2016 release—seven years after a federal judge ordered it so—he spent a total of fifteen years in detainment with no proof he ever participated in a crime against the United States.

The movie, which is a close-up case study of both savagery and inexplicable fortitude, also has something else going for it—well, a few things—it forces a reckoning with the political doctrines that justify Guantanamo’s existence while sidestepping any Hollywood white savior pitfalls, impressive given that the broader brush heroics in the film come on behalf of Jodie Foster as a no nonsense pro-bono attorney determined to get Salhi his day in court, and a U.S. Amy colonel, played by Benedict Cumberbatch, who tows the line until his God-fearing morality no longer allows him to. All three stories are compelling.

With a screenplay by Roray Haines, Sohrab Noshirvani and MB Traven that hews closely to the events of Salhi’s book, the picture benefits considerably from an emotionally raw performance from Tahar Rahim (A Prophet) at its center. Given the Hollywood heavyweights on the other sides of this acting triangle, the picture never loses focus of whose story is most important to tell.

Picture begins at a family wedding in Mauritania circa November 2011, where Salhi is promptly picked up by police under suspicion of aiding the 9/11 perpetrators. There is no evidence, per se, just tenuous connections—the sort which would never stand in a court of law but in the climate of 2011 were plenty enough for Guantanamo lockup.

Enter Nancy Hollander (Foster), a criminal defense attorney with a national security background and acumen of international law and human rights cases, and assistant Teri Duncan (Shailene Woodley). As Nancy advises her protégé, their concern is not Salhi’s guilt or innocence, but his access to a mere hearing after seven long years of detention without charges.

Foster, reminding us how good she was in investigative mode in The Silence of the Lambs, is sensational. There are moments here where she pours over top secret and redacted documents, making discoveries and gaining insights into Guantanamo’s heinous activities that are minimalist and undeniably affecting, told in simple close-ups.

Cumberbatch, sporting a sometimes too-broad southern drawl, is also very good, and very pivotal to The Mauritanian’s moral center, as the God-fearing southern colonel and government ambassador in charge of keeping Salhi confined; his crisis of conscience upon learning case specifics while applying personal morality to his role as prosecutor is critical to the film’s thesis – if more people knew, or looked into what was really happening at Guantanamo, and abandoned partisan jingoism in favor of shared humanity, the facility would surely cease to exist.

But it is French-Algerian actor Rahim, a real movie star, who delivers the film’s knockout final third, particularly during a shock sequence—and perhaps the reason the film exists—where the horror of his incarceration is revealed in scenes of cruelty that may come directly from the headlines, but writ large in a movie this accomplished provoke disbelief and outrage to anyone with a conscience. These ten potent minutes, which depict waterboarding, beatings, viciously barking German Shepherds, nightmarish hallucinations, strobe lights and darkness are effectively intercut with scenes of Hollander digging through scores of documents on the torture; her reaction is surrogacy for ours. In this sequence, McDonald (The Last King of Scotland) dispels all rationalizations of justifiable, jingoistic inhumanity within a facility adorned by American flags unfurling in the tropical Cuban breeze.

Slahi gets his day in court, eventually, but it’s hard won, and not what we might expect. By the time his story concludes, Slahi has lost years behind bars without a single charge or piece of evidence. The Mauritanian reveres his struggle, the conviction of his attorneys and the awakening of its colonel. It’s an important story well told from all corners.

3 stars.