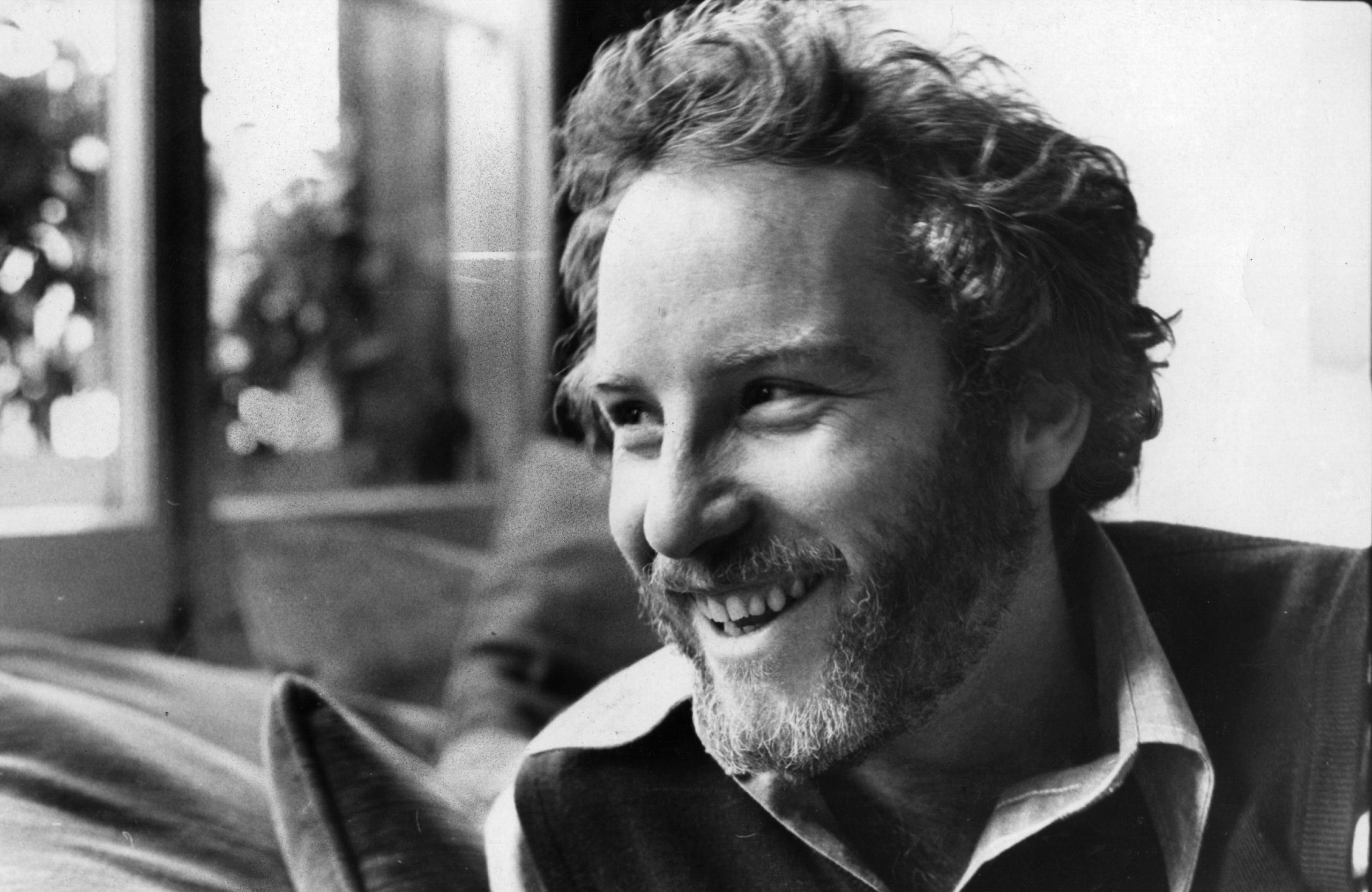

It would be difficult to overestimate the impact that Richard Dreyfuss has had on American culture, his sort of whip-smart, articulate neuroses and acute attention to, as he puts it, inner heroics, a staple of his now canonized portraits in a series of seminal movie classics.

Dreyfuss, an indelible actor whose signature characters in Steven Spielberg’s Jaws and Close Encounters of the Third Kind, have, in retrospect, made him an icon of sorts, got his start in George Lucas’ American Graffiti and rode a wave of A-list pictures to an Oscar win for Neil Simon’s 1977 The Goodbye Girl.

It would be easy, as many do, to define his legacy by those four pictures, all history book contributions most actors would give their left audition for, but Dreyfuss, that most original of American leading men, was never content to coast on those landmarks. Richly distinctive, his is the kind of career where we all have our favorite performances and there are so many great ones that our personal beloveds might never overlap.

Dreyfuss is what you’d call an elevator actor, meaning he raises or elevates everything he’s in, a sort of highly watchable, comically acerbic, turn-on-a-dime dead serious and bona fide movie star with acting chops, as moving in Mr. Holland’s Opus and Stand by Me as he is ribaldly hilarious in pictures like Down and Out in Beverly Hills, Tin Men and Stakeout.

And we haven’t even mentioned some of his lesser talked about works, like the youthful The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz, which put him on the map, his rigorous right-to-die portrait in Whose Life is it Anyway?, the endearing exasperation of Once Around and a few others I’ll get to in a moment.

We could do this all day.

Dreyfuss will be in Chicago this Thursday, January 31, for a very special Classic Cinemas event, An Evening Jawing with Richard Dreyfuss, at the Tivoli Theatre in Downer’s Grove, where his fans will have an opportunity to catch up with the famed star for a Q&A followed by a special screening of Jaws. “They’re going to need a bigger theater,” might be the tagline of the night. Dreyfuss, who in recent public appearances commands thousands of admirers, is sure to fill the house.

I caught up with Richard Dreyfuss recently to talk about his career, its origins, how he looks for characters, his thoughts on the industry of the ‘70s versus today and some revealing observations, which have come with age, on his industry colleagues from the era. And of course, as all things today tend to go, we got to a bit of the social and political, and their influences on artists.

But our conversation started with, of all things, the origin of my last name.

Richard Dreyfuss: How do you spell that?

Lee Shoquist: S-H-O-Q-U-I-S-T.

Okay, that’s kind of like, something changed on the way from Russia to Germany, but not enough!

Yes, by way of Sweden somewhere. I met you last year at that crazy Monster Mania convention. You had hundreds of people there waiting, and then the fire marshals came in and they shut the place down for awhile. Do you remember that?

Yeah, I think I do. It was like one of the first I had done. We had a great, long line. At some point I looked up and said, ‘How long have you people been standing here?’

Hours.

Five hours! I just said, ‘You’re kidding me!’ I immediately got coffee for everybody. It became a thing where if you were on Dreyfuss’ line, you get coffee, you get ice cream. I bribe people.

What was interesting was that you took time with everyone you met. I remember you asked me who I was, where I was from, what I did for a living. We had a nice little chat.

Yeah. I realized on being invited down there that it was the only time that I had to ever say thank you to the audience that came to my shows. I thought it was appropriate.

Also, this kind of audience- they’re a die-hard audience for decades and decades, and they continue to watch the stuff. It becomes a sort of a real thing in their lives, forever, in a way. It’s not just a movie that’s put on the shelf. The whole power of nostalgia, of the movies in the ’80s and ’70s. It’s a real thing you know?

Well, they have a thing in politics—they say if a politician shakes your hand at an airport it’s worth 35,000 votes.

There you go.

And you’ll always have that vote, no matter what, and you’ll have the votes of that family. Whether that’s true or not, I don’t really know. I thought to myself, well, maybe there’s a corollary; a kind of hang over into show business. But I’ve come to the conclusion that as affectionate as people are, as sweet as they are to me, it doesn’t really clearly translate to, ‘Oh, let’s go to see another movie of his.’ I can tell you that’s my financial acumen at work.

I was reading something you said once about the life of actors at the top being up and down, or something like that. You said you had spent some time up there and you didn’t want to live up there forever and decided not to.

Right, exactly right. I turned down certain projects throughout my life to keep me from being in that too rarefied atmosphere. Because I wasn’t, and I’m not, comfortable not living among human beings and going to retail stores and buying an orange. The thing they don’t tell you is that George Clooney, for instance, lives where he lives because he’s under attack anywhere else. There’s a certain kind of circle of people who are at least, at first, just hiding in their homes. Then maybe they create a society. I don’t know. I just didn’t want to go through that.

Yet you knew you wanted to be an actor when you were eight years old.

Yeah.

You told your mother you wanted to do it, and then you started doing it at a community center. What bit you early on? What was it?

I don’t know. The one thing I can’t answer is the ‘why’ of it. I can’t tell you ‘why.’ I just knew. I knew- I usually say eight or nine, but I was already an actor before my memory begins. That was a given. It was a done deal. The virtue- the great part of it was that I was so certain that I would succeed, that I would prevail and be a star, that I had incredible patience. I wasn’t in any hurry. And so I really enjoyed the years of what I call my ‘apprenticeship.’ I mean, I really did. I enjoyed going to unemployment, and I enjoyed going to classes, and I enjoyed getting roles and not getting roles. I actually ended up teaching a class right around the time of the Oscar. I taught a class in How to be an Unemployed Actor in L.A. I opened attendance to anyone who was essaying a Screen Actor’s Guild membership. That was it. That was the only thing. And then they had to pay me.

I taught them how to seduce casting directors and make your agent your best friend. How to take over an audition and how to lose a part, and how not to, and how to walk away. There were 650 people in the audience on a weekly basis for six months. I introduced them to and interviewed all the casting people I knew, and the agents and showrunners and stuff. Many hated me afterwards because I turned to the audience and said, ‘Give him a call!’ They hated me for that.

You mentioned the Oscar. When you win one, or you have a high point in your career, do you still go back to the feeling that you’re then an unemployed actor again until the next thing comes around? You’re always in that sort of state after you’ve had a big success?

RD: No. I knew that I had arrived somewhere. The problem was, if you asked me, then or now, ‘What is the name of the book you haven’t written yet Richard—your autobiography?’ I would say it would be called The Hunt. I was much more comfortable on the hunt, having to prove to people that I was as good as I thought I was, rather than have them assume that I was. I really felt a difference between those two positions. When I had something to prove, I was great. I was like a lean, efficient jaguar. When I had reached the point where people were just offering me roles in big things and whatever, I was not comfortable. Because I realized I was on my own. I had to show up and do it—great—rather than show up and do it and (hear), ‘Gee, at least he speaks English.’ ‘Gee, he speaks English well!’ ‘God, he’s a really good actor!’ You know?

When you look back at the late ’60s and early ’70s and the kind of golden era of movies that were going on at the time, and think of young actors like yourself versus young actors today, what do you think about the industry now? Of course we’re in a totally different world where the industry is driven by what they call these tent pole movies, and nobody wants to take any risks. Everything’s homogenized now to the point where the distinctiveness of the ’70s seems like it could never happen again.

Let me put it this way. I think a better way to answer this is that last year I started to run into people that I hadn’t seen in 30 or 40 years, or 20 years, or whatever. I found myself realizing that actors are amongst the few people who have really defined relationships. Even with people you haven’t seen in 40 years, we’ve always kept some knowledge of our lives. You’re somewhere and across the room you see Ed Begley Jr., and we both go, ‘Yeah. Oh yeah.’

And so I said last year that I wanted to have a party, and I mean this. I think that everyone who started in the late ’60s and who made the ’70s generation what it was- we all know who we are, and we all know that we are designed differently, perceived differently, and everything that came after was different. When I was about 50, I first said that we had entered the third act; my best friends started to drop dead. And I really feel that we have something to celebrate and toast in ourselves. I’m telling everyone that I see to talk it up. Just talk up the idea that we deserve a party. I am not taking on an obligation for it. But we deserve it and we should have it. If it gets pulled off correctly, the only place that could hold it would be Central Park. Invite all of us, and invite us to say, ‘You’re great,’ before you drop dead.

There’s actually an historical precedent for this because the holy Roman Emperor, Charles V, who was considered to be a very talented holy Roman Emperor, announced his death, and all the kings and queens of Europe came. He sat in the third row, and they eulogized him. He heard all of it, and thanked them, and went to a monastery for 10 years and plucked roses and then he died. And I always thought that everyone should have a Charles V event. Because I didn’t get a chance to say goodbye and to say how much I appreciated a whole bunch of people. I will be the next. It’s coming soon. Whenever you get closer to death than you are to high school graduation, your ideas begin to- you tend to get a little desperate. If you wanted to talk about how I feel now, I feel like we should have a party.

Those people who would be at the party would be folks like myself. I was born in ’68, so I grew up watching movies in the ’70s. I think Jaws was the first movie that I saw in the theater; it was a drive-in theater. Certainly, when I started seeing a lot of movies, I was seeing everything like, for example, The Competition. I think I was 10 years old when I saw The Competition a couple of times. When you talk about that whole group of people that we know are still out there, could be working, and are beloved to a whole generation of us, people like me…

Sure, I mean everybody; if we made films that you were affected by, and if we made films that affected the world, and we did, and anyone with half a brain knows that what happened when the corporate owners took the business back, that it became worse when the quality of things went down. We were reduced to making sequels on sequels on sequels. That generation was given a license and ability to run the asylum for awhile.

I wanted to mention a couple of movies you’re probably not asked about much, but they happen to be some of my favorite performances of yours. I know you get asked a lot about Jaws and Close Encounters of the Third Kind. I want to ask you about the film you made for Lasse Hallström, Once Around. I was always struck by that character. I was moved and I really thought that was an original performance. There’s a scene in the movie that really gets me every time, where Gena Rowlands grabs a microphone out of your hand, if you remember.

Yeah, yeah.

I always thought that was an overlooked movie that just was, absolutely, in terms of the way it depicted that family and those dynamics going on, really moving. I’d love to hear what you think about that.

I’ll tell you the kind of fairy tale story. There was a producer standing on the set of a film that he was making, and a production assistant walked up to him and said, ‘Would you mind reading a script that I have written?’ He said, ‘No problem.’ (The producer) came in the next day and he asked for (the production assistant), and he said, ‘This is going to be my next movie.’ It was Once Around, and it was a true story. When I read it, I just thought it was so beautiful. That’s how we made it. We made it in a very conscious way, about some of the singular eccentricity of this story, which would not have been considered eccentric in 1942.

I’m intensely proud of the film and every actor in it added to it. The guy who played my driver came up with the idea of going around once more; around at the end. I gained a desperately important friendship out of that movie. So, yeah, these are the films that I think people should talk about. If you’re going to have an evening with Richard Dreyfuss, take advantage of it, and don’t ask the questions that—if you thought for one second I’ve already been asked a thousand times—you can hear or already know the answer.

I say to the audience, ‘Look, if you want to talk about Jaws, I’ll tell you this. I know everything there is. If you ask me a question that I have not heard, I’ll give you $10. But if you ask me a question that I have heard, you give me $10.’ I’m way ahead on that one!

This is the curse of a press junket journalism where journalists walk in a room and they say, ‘What made you want to do this? What was it like working with so-and-so?’ And then your interview is over. I typically like to walk in and say, ‘What do you want to talk about that you haven’t talked about all day?’ I start from there.

Yeah! What you should do is say is ‘Let’s have a press conference, not a junket.’ Just have everyone—the way they used to—in the room; 50 journalists yelling and screaming questions. And people get to write what is asked of others, and to others. The experience of that conference is far more dramatic and exciting than the individual coming in and repeating the same questions that we were asked five minutes before.

Tell me something about Inserts. Do you get asked about it much?

Not enough! People don’t know about it.

Not enough. You could probably never make that movie today. Would anybody?

Oh yeah. The only thing that went wrong with Inserts was that they gave it an X. That fucked it up because we didn’t make an X-rated movie. We didn’t make a film that deserved an X rating, but they gave it an X because of the subject matter that we were talking about—the pornographic industry. There’s nothing pornographic in the film. The only thing I would have changed, and I desperately tried to at the time, is to get us an R. That way, you could have actually heard that script and listened to what it was about. It was an amazing and brilliant script.

What about Nuts? I always thought the paring of the two of you in that movie was really inspired. That movie stuck with me.

I think that Barbra has more willingness to work and more energy, more focused concentration than anyone I’ve ever worked with. I question though- I think that because Barbra is Barbra, and she lives in a very rarefied world- she said to me one day, early on, that she really loved the character she was playing because she showed such courage by cursing in front of the judge. I said to her, Barbra, you should go down to the court system because you’ll hear that every day, every minute.

She never did it. She never did and never understood what I was saying. I think that the film actually suffers from a less than acute attention to what is going on here. It was cast with admittedly some of the greatest actors in the United States. At that time, people’s reference points were different. Everyone who was in the movie, Eli (Wallach) and Karl (Malden) and me- everyone, had been doing movies on TV. They were the ones that were doing movies that were broadcast on ABC, so it was not a bringing together of great actors. It was the bringing together again of a bunch of actors (people had) seen every week; it was not the same thing. And no one knew it because no one bothered to look around.

I loved my character and loved her attitude and sympathized and empathized with their problem. I think that Marty Ritt, the director, was too old. He had like three heart attacks and he just didn’t have the muscle anymore. I felt terrible for him because Barbra, who is a very, very, very strong personality, just stepped into the vacancy; stepped into the void and took control of things. As well she should have. But I wish it had been with a greater sense of discovery and astonishment. It was rubbed raw rather than sharp.

You’ve said that there was a phase of your career that people ask you questions about, including Jaws and Close Encounters, which you call the Steven Spielberg phase, and that they were his movies and not necessarily yours, after which you moved on to choices that were ‘your’ movies. If you were to look across everything you’ve done, what you would consider to be your modus operandi for selecting a role? What is it that hits you? Is there some commonality in what you chose to do when you built your career? I know you’re very proud of your body of work, as well as you should be, but I really wonder what it is that strikes you and makes you say, ‘I want to do this.’

I think there are a number of checklist points that I have, and I think that they’re different; a different set of reasons for different films. The story has to be compelling and interesting. The character has to be important in the story. I don’t like playing characters that have no central importance in the story. I don’t like playing characters who are not self-aware. When people see me, and when I see me, I think of a person who has an Upper West Side New York mentality, who is a college graduate, who is a neurotic and very 20th century. I basically think that’s it.

The fact is, I didn’t go to college, and the fact is yes, I lived on the Upper West Side, but I’ve lived a lot of places. But I know who my constituency is, and I think that unconsciously I like to play certain inner heroics. Acting is the fulfillment of a fantasy life. And in the same way as little children we play cowboys and Indians and stick our fingers out and go ‘bang, bang,’ that is acting. I have characters that I like to play. I don’t like to play characters I don’t like to play. And I’m specifically saying, I liked playing Dick Cheney. I liked playing that and saying to an audience, ‘We’ve all got Dick Cheney inside of us.’ Then you look back on your work and you go, well, I think I did pretty good.

What do you think about state of the industry today? There are certain forces in the last couple years that have bore down on the industry; we’re certainly in a world of identity politics now, as we might call it, with seemingly everything that’s being produced under attack, left and right. For example, we’ve seen vicious attacks over Green Book in the last couple months, and it’s not just that one.

Over what?

LS: Green Book. Lots of thinking about movies in terms of what they’re saying to the world and the identities of the people that are in them, and less about maybe the quality of the movie. Have you seen Green Book yet?

No, I don’t know what it is.

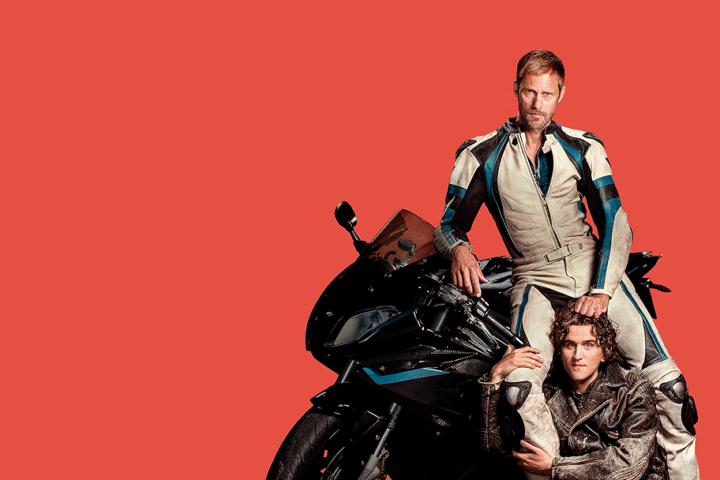

It’s the new film from Peter Farrelly that deals with pre-Civil Rights, race relations, etc. Viggo Mortensen is the white driver of a Mahershala Ali, a Black musician that he’s taking on a tour across the south.

Oh yes, of course!

People are saying, ‘Well this is antiquated, we shouldn’t be talking about this stuff this way in 2019; in 1988 it was Driving Miss Daisy and we’ve evolved.’ That’s one example of how we’re looking at art and artists now through this lens of what’s politically correct today. There’s certainly no shortage of Twitter attacks against artists in movies. I think it’s a real conundrum in the industry. In a way, I think it’s going to hinder artists.

I’ll tell you something, I don’t think it’s any different now than it was in 1938.

No?

It’s only that we have different outlets and we also have committed the following sin: I just read about this attack on Mrs. Pence for going back to work at an art school that had Christian oath involved. People are up in arms. I wrote this little piece and I said, ‘First of all, do we have to comment on everything? Second, is there a surprise here that someone is actually living out the faith that she’s lived in for 40 years? Aren’t we supposed to say, we defend to the death your right to say and do that stuff with which we don’t agree? Isn’t that what America is all about? Who are you people? Shut up. Go listen to the birds for awhile. Relax.’

Artists, in the film business, have always been- ‘Are you pro-Nazi or not Nazi? Are you for Ayn Rand or against Ayn Rand?’ That’s always been there and good health to it. That’s all fine. No one is asking people to make films they don’t believe in. I don’t think it’s any different in that manner than it was before. The enemies were different. When the Nazis were our enemies, they were easy—everyone understood, everyone agreed. Now it’s harder and harder to find an enemy. We went through terrorists, and then we went through Indians, and then we went through rogue intelligence groups and now we’re down to mechanical beasts that grow in the deep ocean. It’s too bad that the people who encourage all this are in power. Then again, these are the movies that make all this money.

You’re a film critic. What you should do, seriously, and you would make a very good name for yourself if you did it- there is a mistake made by every single film journalist in every newspaper and magazine who has written about movies the past 30 years, and it’s very simple. Give you a list of the best, or most popular films of the week or had the best weekend. They do it in terms of numbers.

Numbers are irrelevant. They don’t show you anything because of the word inflation. That means that they’re comparing The Wizard of Oz and Gone with the Wind to today, and it cost $1.25 to see Gone with the Wind, and it cost $15 to go to a movie today. What someone should do is say, ‘I’m not asking that bullshit question, I’m asking, how many tickets were sold? How many clicks?’ If you did that, you’d actually come up with an illuminating piece of knowledge.

Yes. Are you surprised that there hasn’t been more of an artistic response to this administration that we’re living under, the crazy, day to day, outrageous stuff that’s coming down in this country politically and that from an artist’s perspective, we don’t address it? I guess we have Adam McKay’s Vice, certainly. We really haven’t had a great response from the industry to some of the stuff that’s happening. I think we’re so caught up in the fantasy of the superhero movies and box office, as you just mentioned, that we are losing the ability or at least the willingness and desire, of artists to be critical about the establishment.

No. I think that you gain and lose perspective as close or as far as you are from the phenomenon. People right now are still reeling from the astonishment of electing Donald Trump. They don’t know who ‘they’ are. They, the Trumpists, are not over there. They’re here; they’re next door. And you are next door to them. And we aren’t talking to one another. And so we don’t know how to understand this phenomenon. I would think that people putting money into movies are not willing to finance a film that is against everything that Donald Trump stands for, because there’s a whole audience out there—half of the country—that doesn’t seem to agree with you. They would be a little wary of that. Having the intelligence to attack them, or to discuss them with some interesting element is rare. That was rare, by the way, even in the ’30s against the Nazis. It’s a very hard thing to find a film that holds up as intelligent.

I think you’re right about this because if you remember a few months ago, there was a controversy kicked up around the movie, First Man, when it came out of the Toronto Fest. They said, ‘Listen, Neil Armstrong is on the moon, but he’s not planting the flag in the movie.’ That was true. And although the flag appeared in the movie, Donald Trump and Marco Rubio and lots of others started tweeting before seeing the movie that this was un-American, and not an image of the space race that we should be endorsing. A lot of Trump supporters decided they would not see the movie, and that reputation took hold. I think your point about not alienating a percentage of the audience is well taken.

Also, let’s remember here. Let’s not go nuts about this. Charles Lindbergh spoke about how the Jews were forcing us into World War II. Okay? Nobody stopped him from doing that, but he paid a price afterwards. The reality of America is that people have a right to say whatever stupid things they want to say. We should be aware and proud of that. If we’ve got a stupid senator from Florida or a stupid president, we have the right to say they’re stupid. And they have the right to say whatever it is they’re saying. That’s really a gem. That is a gift that America gave to this world. We stopped 10,000 years of homo sapiens’ existence on earth as a shriek of misery and pain and enforced ignorance; until us. We gave a freedom of thought and expression to the whole world. Until us, anytime- if you and I were having a discussion on this same subject at any place in the world earlier than 200 years ago, we would be whispering. I say the meat of what they’re talking about is not important. What’s important is that they’re talking.