You can’t dismiss a B-movie merely for its derivations from other movies—most are predicated upon familiar tropes that usually never fail to get the audience amped up, particularly in the case of horror movies, the genre of all genre movies. Cue the darkness, ominous musical chords and shock cuts and your audience leaves happy. While the pictures may often be familiar (The Possession, anyone?) it doesn’t make them any less fun to watch, particularly when graced with a good cast.

Such is the case with director Mark Tonderai’s The House at the End of the Street (not to be confused with The House by the Cemetery, The House of the Devil, The House at the Edge of the Park or the Last House on the Left), a fitfully entertaining amalgam of haunted house psychodrama and teen angst, courtesy of one Jennifer Lawrence, who if you’re going to wade through a B-movie isn’t a bad guide to have as an Oscar nominee, gorgeous knockout, et al. And in this little throwaway picture, she even sings—lovely.

In an opening sequence that proves it’s never too late to borrow jump cut credits seventeen years after David Fincher originated them in Seven, a little girl—the visage of evil a happy suburban home—brutally murders her parents.

Flash forward several years as teenaged Elissa Cassidy (Lawrence) and doctor/mother Sarah (Elisabeth Shue), refugees from a broken marriage and the big city of Chicago, move in to the rural community (well shot in Ottawa, Canada) and set-up house right next door to the infamous death house, whose existence has caused neighborhood values to plummet.

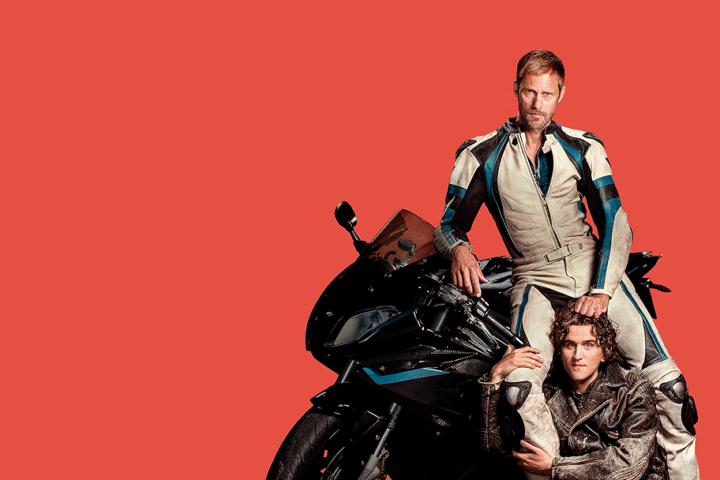

Though warned by gossipy townsfolk to stay away, fledgling musician Elissa befriends loner Ryan Jacobsen (Max Thieriot), the sole survivor of the massacre, a shy but seemingly kind kid who’s a pariah in the community but really seems to just be misunderstood.

Concerned Sarah (a former wayward mom parenting on overdrive) warns the duo about spending time together alone, but tensions between mother and daughter plus the usual teen rebellion mean that Elissa is soon sneaking away every night with the sensitive young hunk. In a convenient plot device, mom is waylaid on the night shift at the local ER.

It’s not giving anything away to say that Ryan’s sister and former murderess Carrie Anne, believed by the community to have drowned years earlier, is locked away in the house’s basement beneath a basement, under his care as part of some sick, sibling codependence. She frequently attempts escape and is, it’s suggested, fiercely protective of her big brother. Watch out, Elissa. But not quite.

And that’s about all you can say about The House at the End of the Street, because just when you think you’re settling into a story about two misfits falling for each other under bizarre circumstances and the pace begins to flag, screenwriter David Loucka, working from a story by Jonathan Mostow, produces a novel and highly enjoyable twist that is impossible to see coming, changing the direction and meaning of the movie as well as its take on young Ryan, dispensing with the empathy the screenplay had previously given him.

Lawrence is the main reason to see The House at the End of the Street, ably supported by Shue and especially Thieriot, whose face is like a prototype of sensitivity and has been effective in such movies as Chloe and The Astronaut Farmer. As actors, she is a naturalist and he a mannered minimalist, an combination that seems about right here.

The young star, who apparently can do just about anything after her Oscar nomination for Winter’s Bone, her brief and sad turn in Like Crazy and her The Hunger Games warrior, is so confident and radiates such intelligence in each scene (watch her reactions in an early lawn party scene when a key story is told) that you can’t help but think she is slumming a bit here, try as she might to raise the stakes. The buzz on her work in the upcoming Silver Linings Playbook has her headed for a potential Oscar. At 22, she’s already world-class.

The climax borrows liberally from Disturbia, The Silence of the Lambs and even—would you believe—notorious 1983 slasher Sleepaway Camp in its final scene. It’s so familiar it even has a tinge of The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo somewhere buried in its subterranean lair. None of this makes the tension any less or the thrills any cheaper, and the final reel really ratchets up the tension.

But perhaps the ultimate message in The House at the End of the Street is a simple one—at the end of the day, sometimes mom really does know best. The picture is a time waster, but you could do worse.

2 1/2 stars.