Gerard Butler has played some epic characters in his prolific Hollywood career—Beowulf (Beowulf and Grendel) and King Leonidas (300) come to mind, as well as his upcoming turn in Ralph Fiennes Coriolanus. But perhaps his latest role, as a crusading American missionary who takes on an evil African warlord to protect a country’s children—it’s all true, by the way—is perhaps his most epic, the story of a flawed man who hits rock bottom to find redemption as both a savior and an unlikely mercenary.

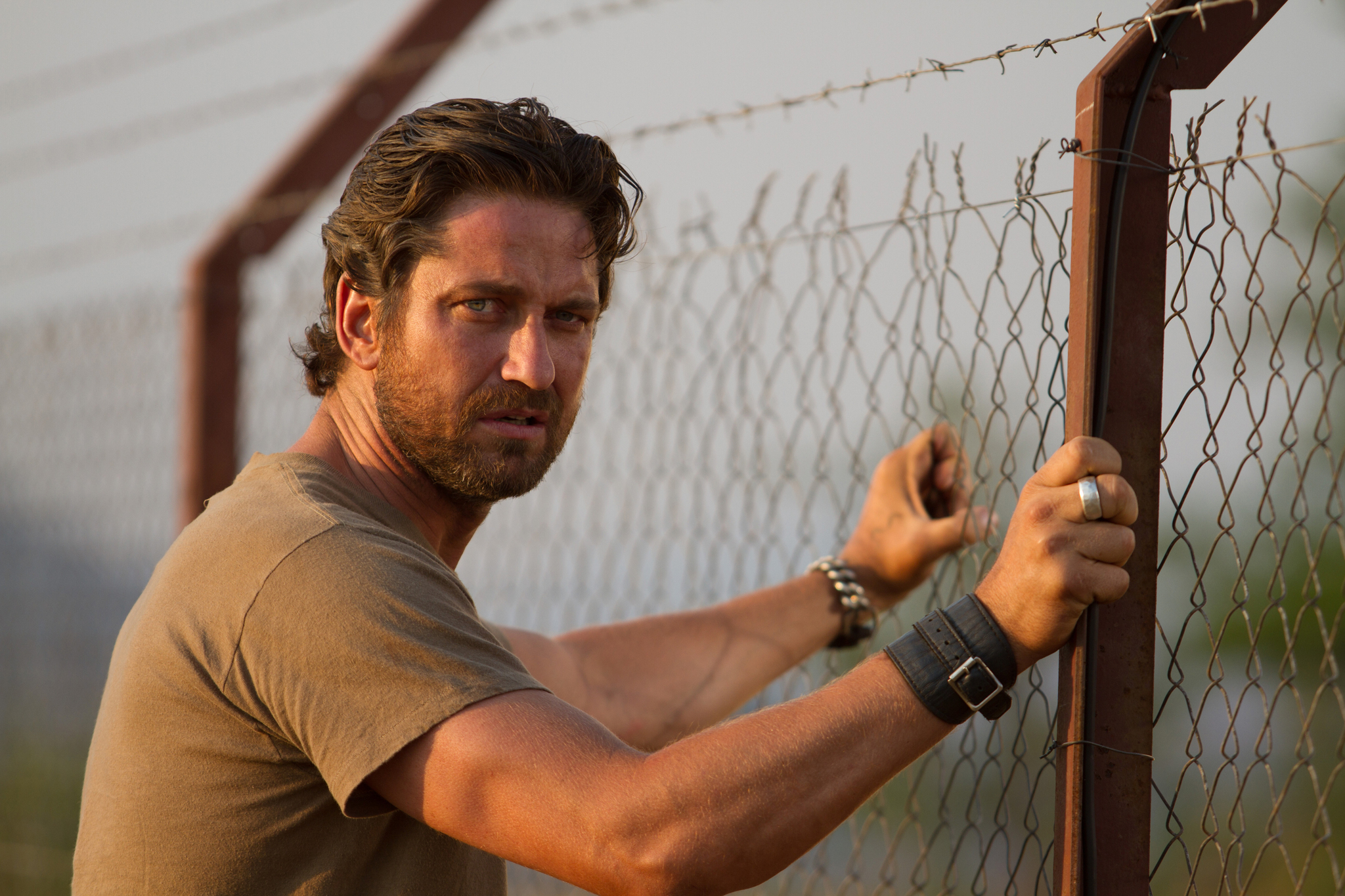

His new picture, Machine Gun Preacher, was a labor of love for the actor, starring as real-life born-again minister and African missionary Sam Childers, who spent the early part of his life in trouble with the law before undergoing a spiritual conversion that led him to a Sudanese revolution. The actor, who also executive produced the picture, directed by Marc Forster (Monster’s Ball, Finding Neverland), spent significant time and personal resources to get the passion project off the ground, a test of faith, endurance, stops and stars, much like his real-life counterpart, a man of contradictions, both compassionate and calculated.

Butler, the Scottish star whose movie star looks are often employed dress up underwhelming fare like The Ugly Truth, Gamer and Law Abiding Citizen, delivers a commanding performance in an ambitious movie, one that plumbs despair and joy equally, a high wire he walks most convincingly.

I caught up with Gerard Butler recently to chat about Machine Gun Preacher’s maverick character, and found him as charming in person as onscreen, clearly with strong emotional ties to the film’s paternal dimensions and obviously moved by his process of connecting with both his real-life counterpart and the African children on set.

You’ve played many larger-than-life characters. Perhaps Sam Childers is the largest. You’re not afraid to play him rough and unlikable at times, and I know you’ve said you wanted to bring integrity to him.

I can’t compare Sam to other characters that I’ve played that could be considered larger-than-life. A lot of them are stylistically big—The Phantom of the Opera, Beowulf, Leonidas—whereas Sam is a very charismatic man, but still a man. What I really connected with was the fact that he had all of that going on and he incredible courage and determination and endurance.

And yet he is full of shame and anger and the violence simmers under the surface. To me, that was how to make this character more fascinating; to get all of those parts of him. We weren’t making a movie about a hero here, even though he is a hero. We wanted to show the downside; that not everyone agrees what he is doing and it costs him his family. To me, that was perhaps what kept it from being over-the-top—playing his determination and that ferocious part of him, yet showing him as just a man who is, in some ways, scared. At one moment he is Mr. Cool and other times he has tears in his eyes.

He has a lot to say and he is a fascinating guy. Something started to build within me the more I listened to him and watched him. I read his book and got such a sense of him. I watched him preaching, various footage of him and interviews, and I always had them playing in the background.

You mention the ferocious part of him, which often comes across in his sermons. You really play him as on the edge.

I did all of my preaching scenes in one day and I improvised, stole some stuff and YouTube-d many preachers. What was fascinating to me was this belief they have in the power of God and feel protected in every way. And yet I wanted to play him in quite an impure way, because a lot of his preaching is coming from a place of fanaticism and not within the realm of a healthy sermon by a sane preacher. At times, he really was losing his mind.

There is action in Machine Gun Preacher, but certainly with different implications than some of the other action films where you have appeared. There is much more at stake this time.

If you are doing an action movie like Tomb Raider or Reign of Fire, or even a 300 or a Gamer, of course they are pretty much fiction and stylized and you can detach yourself from the violence. In this movie, it felt very real and is based on actual real violence. That really helped drive me through the story and into the emotion. The action here completely comes from the character and all of it based on real-life incidents. I also had a book that was full of photographs of some of the horrors of this war—villages attacked, bodies bled, limbs cut off, graves full of children, thousands of kids holding AKAs. I could go on. But this is what I used to get me into these scenes. Therefore, I was never really looking at this violence as fake because I knew it was real. It never felt in any way like an action movie, but rather a character-based drama. It just so happened that this character got involved in those situations. I was literally blown away when I saw the film and saw those scenes. But the most powerful were the emotional moments when he was alone or with a family member. As a person he went through so much. That is what I reacted to.

A large percentage of your screen time in the picture you spend with the African children, many of which are quite remarkable.

That would be my favorite thing about working on this movie. In the news you hear about what is happening with kids and the family unit and what is happening in the world. Meeting these kids gave me much faith and pride about our future leaders. For instance, my two young kids in the movie were such phenomenal girls; smart and funny. And getting to know the kids in Africa was truly the most fun experience. I found that to be profound. Then you connect and realize that they are the same kids who are being hacked to death and forced to hack others to death, going through those unspeakable horrors, damaged. I spent more time in this movie holding hands with them and with my arms around them. Getting to know these kids and playing with them was truly my favorite time on this movie. And then I would go back to that book and open it, and look at those kids. It was tough (begins to tear up, pausing). It was a tough movie to do but it was an honor to tell their story.

Movies have the power to change people and lift us out of our lives and mobilize us toward things we might not otherwise observe or get involved with. But do movies have the power to change the actors who are in them? If so, what did this one do for you? When you move on to another film like The Ugly Truth or Law Abiding Citizen, or something lighter, is there a residual effect from a film like this that perhaps you take away that maybe you wouldn’t from another?

I think I take away what any audience member would, which would be hopefully to be inspired, touched and have an appreciation of things going on elsewhere which don’t immediately affect our lives; to be educated by that. For me, this film was a complete education. Despite going through that experience, I have to take each project on an individual basis. In truth, I am an actor and I get into a role. I am impacted by a role, but I can’t say that every scene I play in a movie changes my life. It doesn’t mean after doing something so heavily dramatic and powerful that I am going to do The Ugly Truth and take nothing from it or feel guilty. I would focus on the fun. This was the time to take on a very valuable character and pass on a message. People will take out of this what they have to, and maybe nothing, but I can’t imagine for a second that people won’t be impacted by this because I have never been so impacted by a script that I have read. And I think the film has that same feeling.

It’s true that the surprise success of 300 transformed your career. Can you describe that turning point and subsequent experiences?

It was fascinating for me. When 300 came out, it was actually a tough time for me. YI felt like I should be high as a kite, and I was high. It was unbelievable to go through that weekend and then hear $40 million, $50 million, $60 million, $70 million and it was amazing. But then I actually found that to be a hard time that I went through. I thought that if I want to make a killing and go on and become Schwarzenegger, Bruce Willis or Jason Statham, I could go down that line and make those movies. Or I could take a gamble—and this was a watershed—and people would go, “Really? The guy from 300 is doing Nim’s Island or P.S. I Love You?”

It was time to say, “Okay, I have the action. Let’s go off and do some comedy or an animated movie or dramatic movie.” And for longevity, for my own satisfaction and to keep my own creative juices going, that is what has always excited me about being an actor. I wouldn’t say I’m the best actor in the world, but I think I have a lot of variety and I can take myself to a lot of places that I think not a lot of actors can. To have people go, “Wow, I didn’t think he could do that,” like the Shakespeare project (Coriolanus) I just worked on with Ralph Fiennes, these are things you want to run a mile from. But then you will always know you ran a mile. If I have the opportunity to challenge myself and then I don’t… Sometimes I will get a project and be shit-scared of it. Right now it’s a surfing film. I couldn’t surf for shit. I know it is easy to say, “Learn to surf a bit.” That is five words, but actually six months of your life to learn! But that is where I derive my sense of fun is by challenging myself.