James Wan’s splendidly creepy, first-class haunted house picture The Conjuring is a welcome throwback to a genre all but forgotten by Hollywood’s labored, modern CGI thrillers. Featuring expert craftsmanship that makes superlative use of light, darkness, sound and production design, The Conjuring is a high-order hair-raiser that takes its subject—demonic possession, its relationship to faith and toll on an unsuspecting family—seriously, and works overtime to build and sustain a rising dread. There are shocks galore in this primal movie, all earned in a picture that nods to Poltergeist, The Amityville Horror and The Exorcist, standing with the genre’s best. Things go bump—and then BUMP—in the night in The Conjuring, and it makes for one hell of a scary movie and a masterful exercise in atmosphere and suggestion.

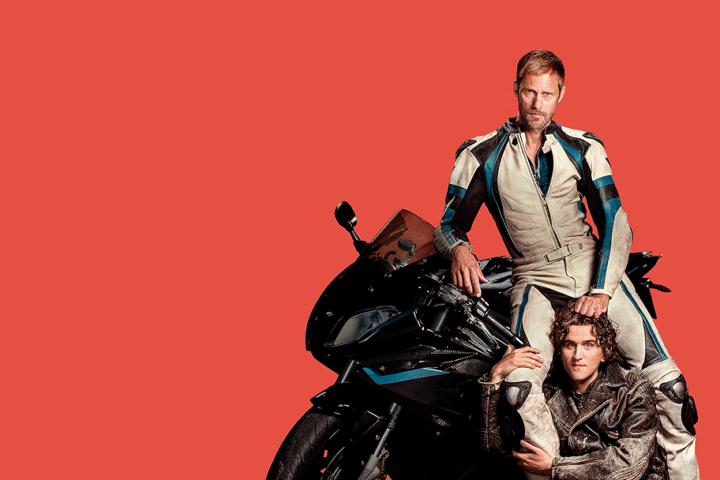

Based on the supposedly true story of a 1971 Rhode Island haunting so shocking the participants refused to speak of it for decades and featuring a lovingly detailed period recreation, The Conjuring comes from the case files of “demonologist” husband and wife team Ed and Lorraine Warren (Patrick Wilson, Vera Farmiga) who later famously took on the notorious Amityville haunting. We first meet the pair during a highly unsettling prologue after a malevolent spirit manifests the body of a rag doll so creepy the hair on my arms actually stood up in the film’s opening shot.

The Warrens see their job as one of debunking illegitimate phenomena while lecturing on university campuses about faith and the war against evil, and their home features a museum-like “off-limits” room containing souvenir artifacts of their craft, including the dreaded doll from the film’s opening scene, who naturally makes a return appearance late in the picture.

It was 1971 when Roger and Carolyn Perron (Ron Livingston, Lili Taylor) and their five daughters moved into their Rhode Island dream home, a lakeside fixer-upper with a secret past involving witchcraft and matricide. Almost immediately, the family is set upon by a malevolent “dark entity” that initially seems like a poltergeist, slamming doors, stopping clocks and disturbing the family pet.

But as the incidents escalate into the realm of physical threats, the terrified mother seeks the Warrens’ expertise in unraveling the mystery and banishing the demon, positing the classic haunted house scenario of paranormal researchers setting up shop on the ghostly premises and setting the stage for a hell breaks loose climax of possession and exorcism, the Warrens intervening to do battle with the very nasty phantasm.

The catalogue of scares in The Conjuring won’t surprise anyone who has seen a haunted house picture, from 1963’s The Haunting to 1973’s The Legend of Hell House, but The Conjuring holds its own in the genre. It’s certainly better than the tepid 1979 groaner The Amityville Horror, and the final possession sequence—victim writhing, moaning and levitating beneath a blanket—nods to, and gets considerable mileage out of, The Exorcist’s visceral shocks.

Special mention should be made of Julie Berghoff’s dazzling production design, which takes us through the house’s hidden, byzantine byways including a secret compartment behind a wardrobe and into creepy, claustrophobic shafts between walls that lead to an expertly dank and foreboding hidden cellar. There’s also a shot late in the picture of the Warrens’ young daughter, descending a staircase during a rainstorm, red shag carpet, vintage wallpaper and flowery nightgown all feeling like a throwback to, in my book, Stanley Kubrick’s classic 1980 adaptation of Stephen King’s The Shining. It’s one of those shots you want to hold onto, drink in even, and The Conjuring is a textbook marriage of such art direction and composition.

Cinematographer John Leonetti’s widescreen lensing evocatively plays with light and dark, and what is just out of frame, at times capturing different characters moving through the house—the camera swoops from staircase to foyer and into disorienting inversions, even employing an effective use of the zoom in, dolly out technique, effectively ratcheting up the paranoia.

Both Wilson and the highly empathetic Taylor (who also starred in Jan de Bont’s tepid 1999 remake of The Haunting) deliver rich characterizations as the supportive husband who has seen evil up close and the concerned mother veering into madness. But it’s the impressive Farmiga, investing a familiar role with gravitas and emotional fragility, who delivers the film’s most compelling portrait. Eyes, ears and body registering every thump and vision that her clairvoyance tunes in to, her Lorraine is a woman of faith, devoted to her husband, daughter and the preservation of good in the world—even when staring straight in the face of devils she alone can see. Also notable is young actress Joey King (White House Down), registering effective fright as the daughter most likely to be the object of the entity’s attentions.

If not on the order of Ellen Burstyn’s tortured mother in The Exorcist, for which she was awarded an Oscar nod, The Conjuring’s screenplay by Chad and Carey Hayes (who also penned 2007’s dismal Hilary Swank vehicle The Reaping) treats its spiritual crises seriously, giving the picture depth and consequence, evident in mother Carolyn’s maternal goodness and the clear bond between the Warrens, who see their union as a spiritual partnership ordained to ward off evil.

Wan, graduating to his sixth picture after massive hits like 2004’s original Saw (one of the frontrunners in the torture-porn genre) and the 2010 shocker Insidious (in many ways a prelude to The Conjuring with its haunted family and spectral visions) and on a scant budget of $13 million, is in full control of both technique and narrative, delivering one of the year’s big movie surprises. He knows that what we cannot see is what scares us, and The Conjuring’s canny exploitation of our deepest, basic fears—the dark, something in the closet, the loss of family—sends it over the top.

4 stars.