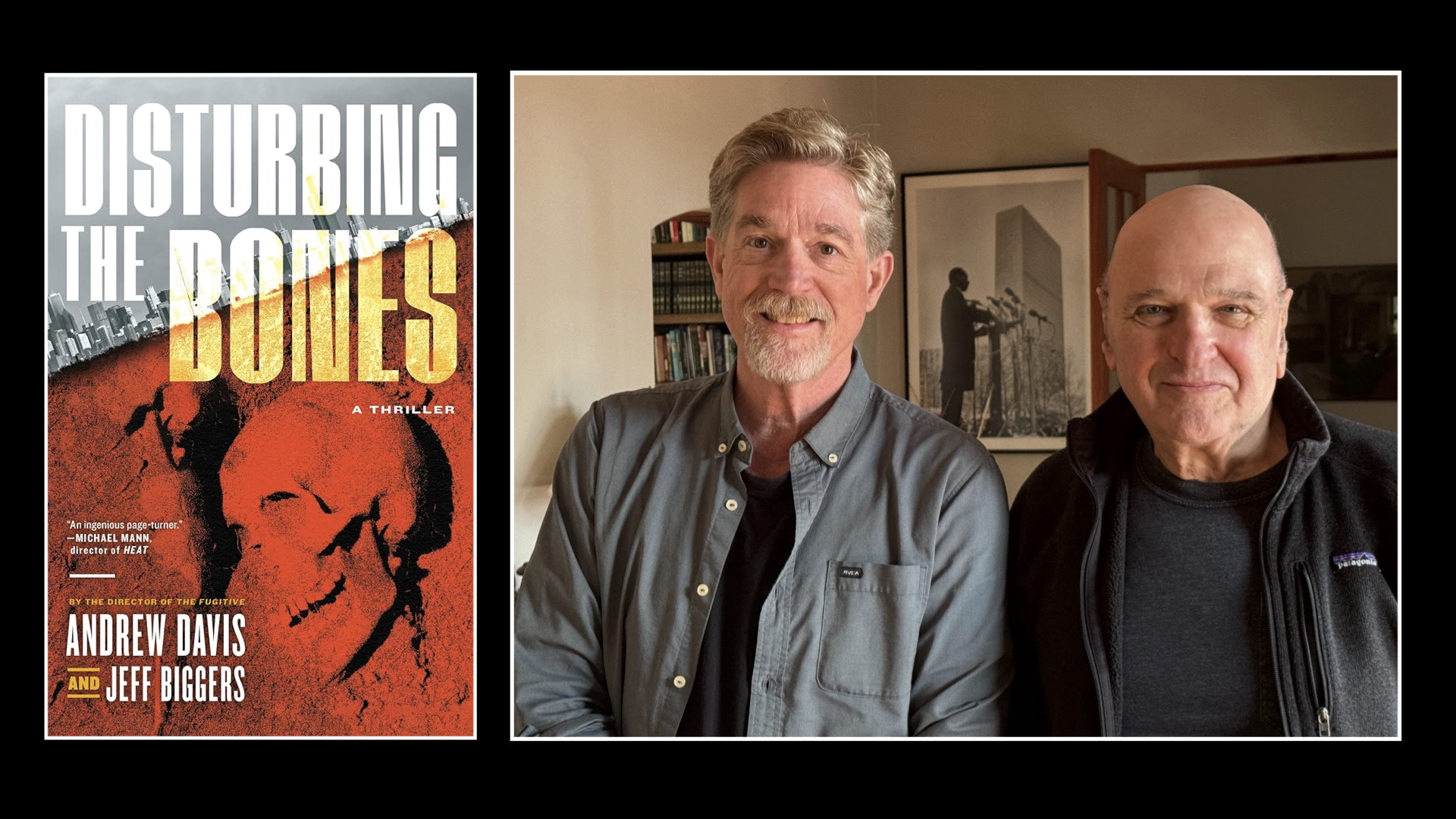

In their ambitious new novel Disturbing the Bones (Penguin Random House), hit filmmaker Andrew Davis and historian-novelist Jeff Biggers have crafted a high-tech, riveting thriller that interweaves geopolitical thrills and a personal, eras-spanning mystery. This isn’t just a whodunnit; it’s a politically charged race against time and an intricate meditation on confronting long-buried ghosts, resurfacing to reveal dark truths that bridge past and present.

Disturbing the Bones follows a young archaeologist on a dig in historic Cairo, Illinois, who unwittingly uncovers a link between a long unsolved mystery and a pressure cooker of present-day political tensions. After the remains of a former Ebony magazine journalist who went missing decades ago lead to a veteran Chicago detective haunted by his mother’s disappearance, a web of secrets reveals a powerful network of military and political elites in a massive conspiracy that just might end the world. In a race against time, the pair of unlikely protagonists must confront complex family legacies to prevent a geopolitical catastrophe.

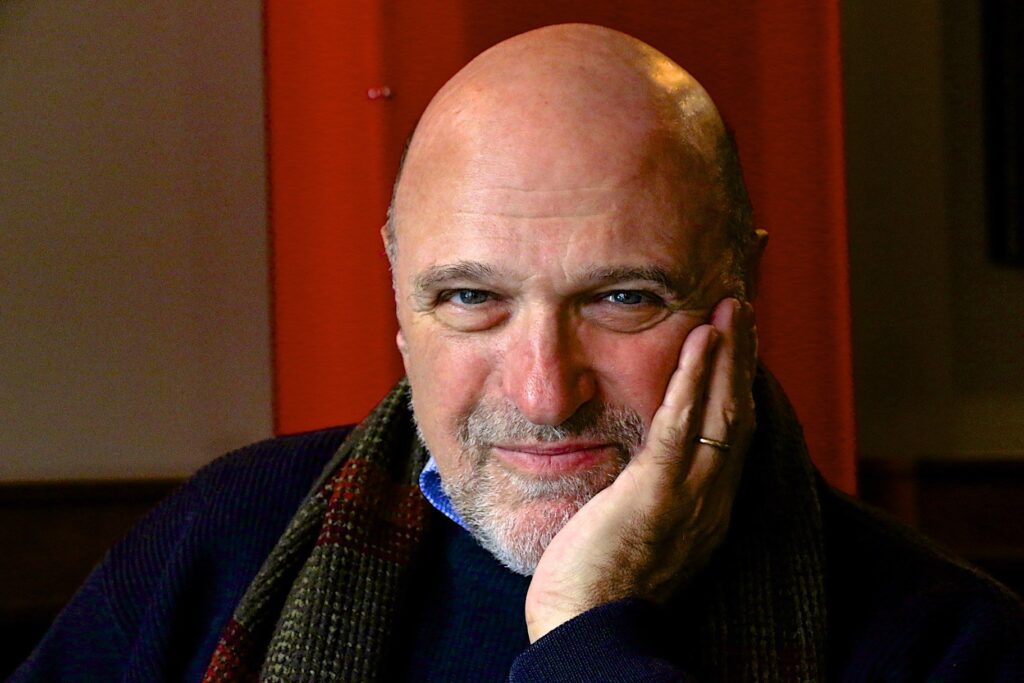

Davis, the acclaimed Chicago filmmaker behind Oscar-nominated The Fugitive and action-packed pictures like The Package, Under Siege, Above the Law, Collateral Damage and Chain Reaction, channels cinema into every passage, mounting literary sequences so elaborate they practically demand to leap from page to screen. In a recent chat, he shared the journey behind his first novel.

I didn’t know much about the book before diving in, so I had no idea what to expect. I nearly read it cover to cover—it’s the definition of a page-turner. At first, it felt like it might be an exploration of personal and racial history in Cairo, but it quickly transformed into a geopolitical conspiracy thriller with a huge, unexpected climax. I was constantly picturing it as a movie and even imagined a full cast as I read. How did this story start for you, and what led it to become what it is?

Andrew Davis: It started as a screenplay and based upon the archaeological dig that I had heard about many years ago, where it one site they found 26 layers going back 13,000 years. And then when I did The Package, it triggered me (to wonder) what we would be remembered as. When everything is gone, we’ll have our missile silos and our bunkers under the ground. Maybe if we’ve killed each other with all these atomic weapons that is what will be remaining.

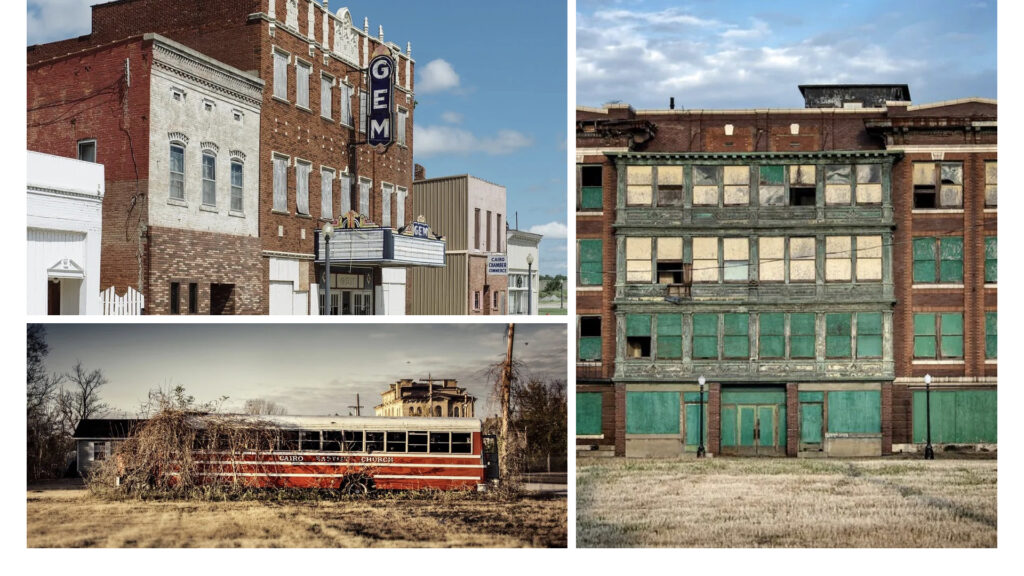

And the idea of Cairo was something that haunted me because I was thinking about what happened along these rivers; what happened down in southern Illinois. In Cairo, something that I was aware of from the 60s—John Lewis, Julian Bond and Jesse Jackson were there—was a focus of civil rights issues. Blacks boycotted downtown and the Klan and the Nazis came down from Chicago. So it was a very interesting mix of elements that I thought would work. And The Package was a movie that had this incredible reality of the generals from both the Soviet Union and Russia, and the United States didn’t want to give up their weapons. I started working with a screenplay and had been working on it for quite a while. And then I met Jeff Biggers and asked him to help me with the screenplay because he knew all about southern Illinois and Cairo. He’s a very good writer. We started working on it and after a while I got frustrated. I wanted to put in all of this texture, backstory and history. I said, ‘Let’s write a novel and we will extract the best of it and then go back to the screenplay.’

Cairo has a unique, storied history that you bring fully to life in the book, especially in the second half. Its geography and evolution—from its boom years to the civil rights era and some of its darker moments—create a strong sense of place. Alongside the action and geopolitical intrigue, there’s a fascinating excavation of the heartland here.

AD: Location has always been important to me in my movies, but you have got to have characters you care about and a moral to the story. You’ve got to have someone to cheer for and hopefully the good guys win. So it was something that I think needed to be explored, and the layers were going through history and what we remembered, and to modern life. It was a tapestry, finding the balance between the personal stories, the action and the real politics. I love that it’s got a presidential candidate from the South side of Chicago who is an African-American woman. We wrote this well before Kamala Harris was running. It’s bizarre that it is in the headlines now. I just hope there isn’t a Russian missile accident.

Besides the new president in the book, there’s also the outgoing president, who is, let’s say, not too subtly depicted. I had fun with the descriptions of this sitting president, especially his branding of his opponent as “Insane Elaine.” It’s a playful jab at current cultural tensions, which, honestly, aren’t too fun these days. Then, there’s your protagonist, Randall Jenkins—a weary, perhaps 60-something Chicago detective who’s seen it all. He’s fascinating as the story unfolds, going through quite a transformation. And then there’s archaeological rising star Molly Moore, a stark contrast to him, yet equally intriguing. You brought these two together not only in this conspiracy thriller but also through their unexpectedly interwoven family histories.

AD: Originally, the archaeologist was to be a middle-aged man (and it became) a young woman who finds the body of a former Ebony magazine journalist in the ground amongst all these ruins. It turns out to be the mother of the Chicago cop who lost her at age 14 and never knew what happened; she just disappeared, and they didn’t know if she ran off or if it was racial tensions and murder. All of these years he’s been haunted and damaged by it. And now this young woman—a gifted archaeologist who went to Yale and has this incredible forensic team—shows up and says, ‘We found your mother.’ And then he finds out her grandfather was in the Klan. I think the dynamics of that relationship are rich as they work together to not only to solve the mystery of what happened to the mother, but to maybe stop the world from blowing up.

You want to have well-rounded characters. Everybody has dimension to their lives with strengths and weaknesses and triumphs and tragedies.

Andrew Davis

I was struck by the moment when he recognizes her last name early in the book, recalling the local family history. The exchanges between his mother and her grandfather, and how they later intersect, were satisfying. I love the idea of the past as prologue, and how it shapes the present. I also enjoyed their symmetry and dynamic, especially how he never fully trusts her until the very end. You mentioned her team, which was an intriguing part of the story. Their forensic archaeology skills go much deeper than expected, and I enjoyed the depth of those ‘side’ characters, particularly Sandeep. The team proves to be much more capable than they initially appear.

AD: This is what universities and graduate schools have. When I went to University of Illinois at Champaign-Urbana the 1960s, there were students from all over the world there. And it exists today. And the fact that we’re dealing with global issues- atomic weapons are global issues whether you’re from India or China. They have this perspective. We also have local people, some whom are not academics and who become important players in the story. And on the other side you have got these military characters who are involved in this secret warfare. In fact, Scott Air Force Base, which we refer to, is where drones are operated from halfway around the world. In our story, there’s a missile test that goes wrong and the Russians basically say, ‘Were you messing with our tests? Did you cause this accident to happen?’ And it’s not very clear what our role was in all that. So there could be jeopardy created by monitoring and there could be jeopardy created by testing. There could be jeopardy created by actually launching missiles or accidents.

That accident early in the book, which introduces the character of Alison, was the first hint that this would be an exciting, big piece of entertainment. The vividness of the writing made it feel like I was watching carefully crafted film sequences. For example, when Randall first visits the dig and everyone converges—reporters, General Alexander, the sheriff—it’s a lengthy, detailed and absorbing passage. There were several situations like this throughout the book that were so well constructed.

AD: I saw it as a movie, and this was an important element—where you get the scope of this archaeological dig. You meet all these local people who turn out to be very intrinsic to the danger of the lives of our principal characters. And then you’ve got Randall confronting the reality of his mother’s death with all these layers of history. What is he going to do? He’s emotionally thrown by dealing with this and realizes it’s strange; it’s in the heat of the night. And I think that’s what you’re dealing with in terms of characters and places.

I enjoyed these sequences, especially the one set at the dig site during the driving rainstorm. There’s also a sabotage and a character falls into the pit, leading to the site’s destruction—another thrilling, movie-like moment on the page. These are enjoyable, cinematic moments, including the plunge into the swamp, which also plays a role in the climax.

AD: I’m going to tell you a funny story about that. Some friends get together with every year from grammar school. A bunch of old guys get together every summer after Labor Day. And last year or so ago, I was on the dock in Wisconsin which collapsed, and we found ourselves in the water. And I lost my phone. The next day my buddy says, ‘I see something down there.’ And I picked up the phone and I could still see my grandchildren’s faces. This iPhone was in the water for more than 24 hours. So when Randall and Molly go into the swamps and they’re being chased, I needed them to have a phone that works again the next day—just put a little hair dryer around it and it was fine.

One character that stood out to me was spunky Aunt Liz, whose actions put her in great potential peril. She risks quite a bit, relying on decades of community trust to do what she believes is right. That brief sequence was as suspenseful as some of the book’s larger scenes. Her importance, along with the family dynamics with cousin Pauline, was well-crafted, especially about the potential mess left behind after others move on.

AD: Yeah, this is the sister of his mother, who disappeared. So she’s quite motivated. I got an email from Jeff last night. There’s a 104-year-old, African-American librarian in Cairo. It is unbelievable how these realities are coming back to us. So it was a way showing the history and how Molly had changed. She cared about the African-American community even though her grandfather was in the Klan. So it was an interesting change and evolution while also hanging onto residual issues.

Molly is depicted as highly accomplished—top of her Ivy League class, groundbreaking experience in Vietnam and still in her mid-to-late 20s. For most of the book, we have a strong sense of who she is. But a pivotal moment comes when her mother and her boyfriend become central to the story. When Molly returns to the cabin and is embraced by her mother, suddenly, she’s not the worldly, accomplished woman but the girl who has returned to her roots and mother’s arms.

AD: Everybody has dimension to their lives with strengths and weaknesses and triumphs and tragedies, so that’s part of who she is. It’s the same with Randall. He’s damaged goods and hasn’t really been able to have a proper marriage and be a proper father, and has been lost in his work. This is a way for him to start resolving what happened and to try to (achieve) justice near the book’s end when the man who killed his mother is discovered. I think you want to have well-rounded characters and we tried to do that.

A brief but important passage involves Sheriff Benton addressing a town hall meeting, where he states that Cairo will not follow federal guidelines on nuclear disarmament or gun control. Reporters press him on the specifics, questioning his assertions of threats and the reasons behind this stance. This exchange made me reflect on the role of the news media in holding public figures accountable. It also highlighted how small, insular communities sometimes choose to disregard federal policies, insisting on handling matters in their own way. As someone from a small town with a local militia, this resonated with me.

AD: Well, there have been sheriffs in different counties who said they were not going to go along with certain laws—not arrest somebody for carrying their weapon openly or for doing certain things that the federal government says is dangerous or illegal. And so this is this dynamic that’s going on right now—which state is going to decide who can have abortions or how they treat immigration. It is very timely in that sense.

In Chicago, we see a similar mindset, as a so-called sanctuary city, where we often do things our way, believing it’s the right approach. For example, if a federal abortion ban were ever imposed, many of us feel protected by the policies of our blue state, knowing we’d be safe in some way regardless of federal actions.

AD: We are facing the possibility that a doctor in Chicago may be violating federal law because they’re providing services to a woman who wants to have an abortion. And I don’t know what the governor of Illinois can do versus the justice department. That could be a very interesting dynamic. We may have a civil war over that.

There are moments in the book where Native Americans are briefly scapegoated as potential culprits, which I found interesting. I also want to mention the detailed security passages surrounding the disarmament treaty, particularly the midnight meetings of various factions, which was a fun touch. And that thwarted drone attack was written with superb suspense, as was the moment with the doctor who has a drone on a south side beach. And the security details and the build-up to the McCormick Place event were fascinating.

Andrew Davis: I’m blown away by how much you remember! I think you remember more of what’s in the book than I do.

Well, I highlighted many passages while reading, including the way people spoke at General Alexander’s bar in Cairo, expressing frustration about politics, immigration, and more. Those moments were observantly written. I initially thought the story would focus on family history or a reckoning with the bones being discovered, but it quickly grew into something much bigger. Randall, despite the personal stakes of his mother’s disappearance, could have easily walked away, but he chooses to pursue the larger fight. Watching him, initially reluctant to return to his hometown, gradually risking his life for the greater cause was absorbing.

So I guess the question is—when is the movie going to happen?

AD: Well, Hollywood is in a very strange state these days. They’re having a lot of trouble figuring out what kind of movies to make. And they don’t make movies like The Fugitive anymore. I think those movies could make money, (but today) there are so many different things people can do. They are on their iPads streaming this and that. Everything is available all the time. And when I look at some of the trade publications like Variety and The Hollywood Reporter, I don’t know who half the people are that they’re talking about, just like I don’t understand the names of all the current music stars. So it’s interesting that there are new icons. You’ve got to sell a lot of tickets to reach a broad audience that can support a budget with big stars and a lot of production and advertising.

Hollywood is in a very strange state these days. They don’t make movies like The Fugitive anymore. There are a lot of great movies still being made and coming from different parts of the world.

Andrew Davis

Don’t you miss the days when you could make a moderately budged film like The Package and create a polished, commercial entertainment that adults would flock to on a Friday or Saturday night? Movies like The Fugitive were the thing to see, and now, we just don’t have that anymore. I lead an assortment of film clubs in Chicago each month, and the few hundred or so members in them—all seasoned moviegoers—really miss it. We used to look at newspaper ads on Fridays to choose from a wide selection of films, many aimed at adults. Now, we don’t even have that option anymore, let alone a newspaper to browse.

AD: Newspapers don’t even have book sections anymore; just getting reviewed is a big deal. There are a lot of great movies still being made and coming from different parts of the world. Young filmmakers ask me to tell me how to get in the business (and how to get) movies posted to Google or Facebook or YouTube. If you have your phone and your computer you can make a movie and get it to a billion people. But now you have to get those people to say, ‘This is special. I’m going to hire this person.’ Who is going to hire you? I don’t know. Being paid to make a movie that gets its money back is a very complicated business situation. It’s very difficult.

When shopping a property like Disturbing the Bones, would you expect studio executives to similarly focus on how it will make money, despite your career success and being an Academy Award-nominated filmmaker for The Fugitive? Is that the conversation?

AD: The relationships I had in the old days, especially with Warner Brothers, were, ‘We like this project. We trust you. We’ve got some big talent that wants to be in it. Go make the movie.’ That was it. Now you have analysts and marketing people and have to know the clicks (the film will receive). The scrutiny is much better. In spite of that, they can still make a movie that loses $250-$300 million right away. So it’s very, very difficult. And they call it intellectual property. Can you sell something that people know nothing about? Does it have to be a Lego? Does it have to be a marble? Does it have to be something like that in order to get people’s attention? Some are interested in experimenting and finding new things and others don’t want to take a chance.

While reading the book, I pictured Wendell Pierce, the terrific African-American actor, as the character of Randall. I wondered if a studio would take the risk of casting him in a lead role like that. He has all the acting skills, a great resume and has delivered superb work in everything he’s been in. But I also wondered if the conversation would shift to needing someone more bankable.

AD: That is the sad reality. I mean, in order to get this moving today with the studio, I need three big actors. And there is still going to be scrutiny about, ‘Is this a story that we can sell around the world? Is it interesting enough? Will people relate to it?’ So those are the dilemmas. I would love to be able to make this film with just the best talent in terms of actors and make it for very little money, but it has got a lot of scope. And even in The Package, which was not expensive, there are a lot of people in it—big crowd scenes and hotels and on the street and stuff like that.

Similarly, there are so many characters in Disturbing the Bones. I was mapping it out on paper, noting who was connected to whom, who was in which family, who was part of the local police and who was implicated at the federal level. With so many characters, how do you develop distinct personality traits, voices and ways of expression? How do you make each one stand out as an individual in such a complex plot?

AD: When I did The Fugitive of one of the executives asked, ‘So what do you need all these people around Tommy Lee Jones for? Just give him a partner.’ And I said, ‘He needs to play against different people. It’ll show who he is. They have a kid with a ponytail and an African-American woman who’s with him and Joey ‘Pants’ (Pantoliano). We needed different people in order to be able to show (his) leadership, empathy and strength. If you think of it as teams, this is the team of the generals and they’re different from each other. One is from the south, one is from Connecticut and the same with the archaeologists. I think that there has been that kind of diversity and complexity to all of the secondary characters that I’ve worked with in stories.

Spoiler alert: the ending of the book surprised me. While there are clear good guys and bad guys, the final sections take an unexpected turn. The missile launch scenario, a potential doomsday, is thwarted, but it doesn’t lead to a happy ending. Instead, it reminded me of the reality faced by many 60s radicals who lived underground for decades, forced to go off the grid. It’s sobering.

AD: I didn’t want to have a happy ending in the sense that everything was going to be fine, but there is a bit of hope because this newly elected president, who has known our main character from the time he was 14, doesn’t believe he’s a terrorist. And she knows there’s been a lot of malfeasance done in trying to stop this peace conference. So you have the feeling that she’s going to support an investigation. Now there have been a lot of commissions and investigations where they didn’t get to the bottom of certain things—like investigating Russia’s involvement in our elections—and where there are things that clearly have happened but the public doesn’t really get to know about it. And so hopefully in this story they will survive and find a way to come back to society and tell what they know.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.