Jeff Nichols’ The Bikeriders, a thundering paen to the birth of American motorcycle culture, is high-gear style and attitude eclipsing a story stuck in neutral. Inspired by Danny Lyon’s 1968 photography book of the same title—which chronicled the circa 60s Chicago exploits of biker club the Outlaws—Nichols doesn’t so much bring the author’s iconic imagery and subjects to dramatic life as provide them plenty of space for posturing.

The extent to which one enjoys The Bikeriders, which has star turns, evocative cinematography and editing and overdrive poseur coolness, is dependent upon embracing such superficial diversions in lieu of narrative substance. Forget getting beneath the skins, and into the hearts, of its fledgling wild ones. Instead, we get a lot of tousled hair, backlit cigarette smoke, two-fisted beat downs, very broad regional accents and plenty of roaring engines. This is not to say that actors Austin Butler, Tom Hardy and (especially) Jodie Comer don’t work hard with what Nichols has given them, an origin tale of a gang named the Vandals that will be tested by crime, tragedy and love. They just don’t have a script matching their investments.

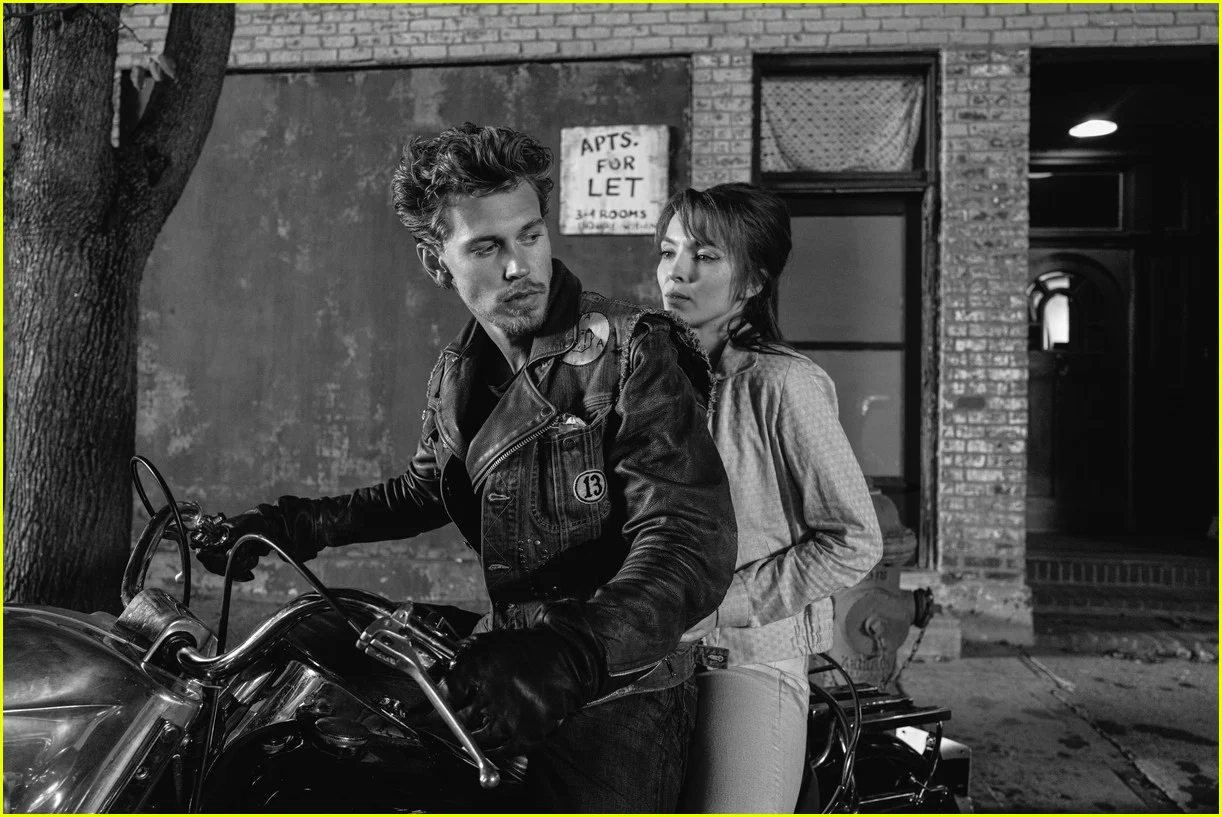

The preternaturally beautiful Butler, in movie star mode and proving his Elvis (for which he should have claimed the Oscar) wattage was no fluke, this time hangs his slicked locks, chiseled cheekbones and drawling baritone on a leather jacketed cipher named Benny, whom we first meet in a local watering hole, dragging on his smokes and—what else—getting into trouble with a couple of local boys looking to take him down a peg. In this introductory moment, the thirty-two-year-old star cuts a mean, handsome line, and Nichols—who has said that his first meeting with Butler confirmed the actor to be the most beautiful man alive—gives his blond-bronzed star plenty of smoldering close-ups. So far, so cool.

Butler’s Benny falls under the tutelage of Vandals founder and leader Johnny (Tom Hardy, in another odd vocal affectation), just getting the gang off the ground as Benny joins, precisely the moment Benny meets Kathy (Comer) in a late night pool hall, his smoldering stare and toned biceps hooking the mild-mannered Midwestern gal, played with no-nonsense directness by the Killing Eve and Tony-winning Prima Facie actress in the film’s best performance.

In a framing device involving a retrospective interview conducted by young Danny Lyon (Mike Faist), Comer’s Kathy recounts the rise and fall of the Vandals’ born to be wild glory, which ensnared to-be husband Benny and caused her considerable grief trying to extricate him from its brotherhood. None of this yields much insight; perhaps Hardy’s Johnny would have been a more illuminating interview subject.

The bulk of this aimless picture mostly charts the misadventures of Johnny and company—a group of charming tough guys including Emory Cohen, Nichols regular Michael Shannon and Norman Reedus, who find fraternity tooling around the city streets and easy riding the midwestern sunsets—never mind the women who want them off the streets, which grow increasingly dangerous with young rival upstarts (Toby Wallace) out for blood.

Nichols has taken a richly excavated, grittily real-life source—and in the film Faist’s Lyon proves perhaps more inquisitive than the filmmaker—and turned it into a glossy, Hollywood entertainment with eminently watchable stars but little thematic relevance. Where is Easy Rider’s nonconformist, counterculture spirt of anarchy? The Wild One’s youthful, establishment rebellion? How about Sons of Anarchy’s character detail? Melodrama of Coppola’s The Outsiders? By contrast, The Bikeriders says little, and does so with cardboard characters. Both Johnny and Benny are blanks; Kathy, slightly more than two dimensional.

Best in show Comer deploys a flattened-vowel, Midwestern accent straight out of the Chicago burbs; it’s accurate all right, as listening to recordings of the real-life Kathy verify. But front-and-center in a feature-length movie it becomes an actorly distraction, Comer presumably compensating for the thinness of her lady-in-waiting character, one pining for change in her preoccupied husband, a wan central conflict for a two-hour film. They argue and make up plenty, and like everything in the film, look great together.

Butler, for his part, dresses up underwritten Benny (he hardly speaks, once, about anything that would define him) with a glamour that the movie expertly trades on. This superficiality extends to Hardy’s tough-guy Johnny as well, whom we know is married and who becomes increasingly weary as the years roll on. But what makes this guy tick? How does he integrate leading the gang with the straight married with children life? What does the birth of this movement mean to him? Bafflingly, Nichols’ screenplay hardly bothers to inquire.

Nichols is a great American filmmaker, and in pictures like the heartland prophecy drama Take Shelter, interracial marriage landmark history Loving and rural portrait of innocence lost Mud he made his mark as a bar none, southern folk and gothic (and fact) chronicler and evocative storyteller. But with The Bikeriders, Nichols delivers his first film that is foremost flash, and not the rebel epic we sense he suspects. In the final moment, the film asks us to care about a development it hasn’t earned, but one that Butler sells with an expression conveying what’s been heretofore missing from his character and the film.

2 stars

A fantastic event..mmmm a great movie. I’m a little bit partial because a Benny -type saved my life long ago And I am grateful….

Thanks for the comment here! Thanks for sharing your story and glad you liked the film!

Saw The Bikeriders in theaters, now streaming it on Peacock, and struck again by the thinness of the story and the weight on the shoulders of the excellent actors (Austin Butler, Tom Hardy and Michael Shannon especially) to pull off the film to watchability.

For instance (*spoiler*) Austin Butler as Benny poignantly in a scene asks Jodie Comer as Kathy to be sure the doctors didn’t remove his injured foot (when he’s under anesthesia, we presume, during an upcoming operation) and the audience hangs on his every word for more about why keeping the foot and riding the bike means so much to his cool/tough guy persona beyond the obvious human desire to remain bodily intact — but we get nothing in terms of story. Instead Jeff NIchols cuts quickly to Kathy’s later narration to Danny Lyon (Mike Faist), apparently based on real (and boring) interviews, where she just whines in the overdone nasal midwestern accent about all the reasons she was annoyed with Benny’s riding.

It’s not like Kathy is some public figure or celebrity icon whose voice is familiar and needed to be authentic as would occur in a biopic of a historic figure. Indeed, the filmmaker’s focused attention to authenticity from some old Danny Lyon tapes of Kathy’s voice, not in an appealing vocal register at all, only detracted from the film’s enjoyment.

Maybe Jeff Nichols just didn’t know how to write an original story that would be meaningful about his most compelling actors in this film. Or he was so enamored personally of Danny Lyon’s photo book (and Austin Butler’s looks) that he couldn’t see past his own artistic infatuation. But, as much as I’m a huge fan of the principal cast (Jodie Comer too when she’s not using a grating accent), I saw their talents underused by an underwritten tale where little happened beyond what we might read in a generic magazine article about biker culture. This cast deserved so much better of the screenwriting, as did the audience!

Thanks for sharing this perspective. I agree that the cast shoulders much of the responsibility of making the film watchable and engaging. Like you, I found that the script did not do the heavy lifting of creating real characters. I often wonder why such capable actors fail to recognize this when they read a project and sign on for it. The scene with the potential foot amputation asks us to infer what it would mean for Benny to lose his foot; Nichols doesn’t provide context up to that point that make it explicit in the story because the importance of the subculture is not genuinely explored. Nichols seems, to me, to be much more preoccupied with the coolness factor of the images, which makes sense given that they were the impetus for his fascination with the subject matter. He just didn’t excavate enough substance from them (even though he clearly used the interviews as well). On the subject of Jodie Comer, a great actress, I believe the slavish authenticity to the accent was completely unnecessary and as you note, a distraction. I believe Nichols was, as you note, too enamored with the romanticism of the tough-cool-guy inconography to go further and meaningfully look beneath it. Scene after scene I could feel the movie operating on a strictly surface level while presenting issues that deserved more; ditto the cast. So we are in agreement and thanks for the terrific assessment you provided!