Bradley Cooper’s Leonard Bernstein picture Maestro, the actor-director’s follow-up to his lauded 2017 version of A Star is Born, finds him confidently back in the musical arena for an unexpected, eras spanning scenes from a (musical) marriage. A Leonard Bernstein biopic turned domestic drama? Come again? Yet that is what Cooper has delivered in this deeply felt matrimonial saga, a bravura piece of risk-reward storytelling and one of 2023’s most decisively artistic, a stylistic fantasia that packs real punch.

Cooper’s A Star is Born redux struck lighting; it was the strongest iteration of the longtime property (and that’s saying something given Judy Garland’s 1954 classic), a rock god fall from grace tale enlivened by true grit and a remarkable Lady Gaga. Now he’s made another tale of an artistic union, this time not threatened by sudden stardom but instead tested by compromise and sacrifice.

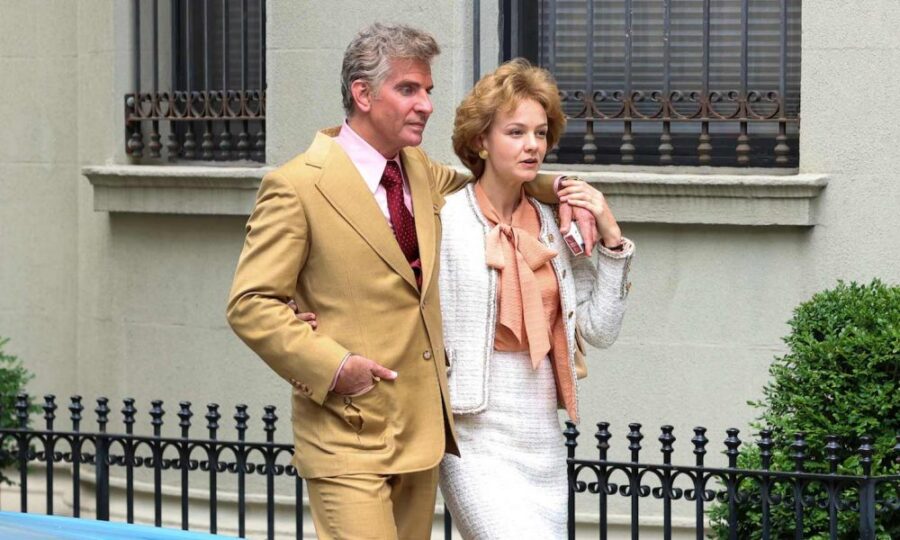

A rousing double act, Maestro stars Cooper (who co-wrote the screenplay with Josh Singer) as Bernstein from youth to old age and Carey Mulligan, in a turnabout from her button pushing Promising Young Woman provocation, as the musical genius’ long-suffering actress spouse Felicia Montealegre, a portrait so richly acted that Mulligan co-authors the film’s impact.

A relatively straightforward story wrapped up in a doozy of a package that includes a mixture of forms, styles and tones, Cooper’s picture is experimental composition as biopic, one that eschews its subject’s prodigious musical milestones in favor of an examination of an enduring love, first progressively nonconformist then tempered, as tends to happen, by the wisdom of age.

When we first meet “Lenny” Bernstein (Cooper), he’s a largely unknown yet hopeful conductor on the rise circa early 40s New York City, where he gets the last-minute chance to substitute conduct the New York Philharmonic, upon which his career instantaneously takes off. He’s also assumptively gay, sharing an apartment and bed with clarinet player David Oppenheim (Matt Bomer).

Enter Chilean actress Felicia Montealegre (Mulligan), whom Lenny meets at a party, the pair forging an instant bond, simpatico in humor, art and eventually, romance. Lenny’s sexual orientation—gay, bisexual, fluid, whatever—is not lost on Felicia, whose own modernity is able to accommodate what she knows to be true, which is that while Lenny may have a complex sexual identity he is also a generational talent. In a sense, she rushes headlong into a series of very big tests.

The first third of the picture shot in the square, Academy aspect ratio of 1.33:1 and in gorgeous high-contrast black and white, their initial courtship scenes a whirlwind of soul connection on and offstage—Felicia making her name on Broadway and Lenny in the concert hall—and both Cooper and Mulligan are exuberantly believable as a couple mutually fueling its advances, in love and on the town, each understanding the other in a privately progressive arrangement.

This courtship turns to marriage in 1951 and a family which includes three children, the most prominent here daughter Jamie, played as a young adult by a good-hearted Maya Hawke. As the film crosses time Lenny’s career skyrockets and major events careen by largely as glorified mentions, including his landmark score for On the Waterfront and composition for West Side Story. For her part, Felicia maintains periodic TV work but is mostly a stay-at-home mom, and eventually Lenny’s dalliances with young men, where his romantic attentions truly lie, become a heavy burden, decades removed from her youthful naïveté.

Eventually Lenny’s extracurricular love life, presented here as self-absorbed, often shallow flirtations, become too much to bear. Jamie endures gossip at college, leading to a brilliant moment in which Lenny lies to his daughter about his identity, and a galvanic holiday argument rendered in a single-take master shot while the Thanksgiving Day parade wages just outside the window. Eventually, the marriage buckles but the deep connection remains, integral to the film’s heartrending final third, as emotional as in an American film in a very long time.

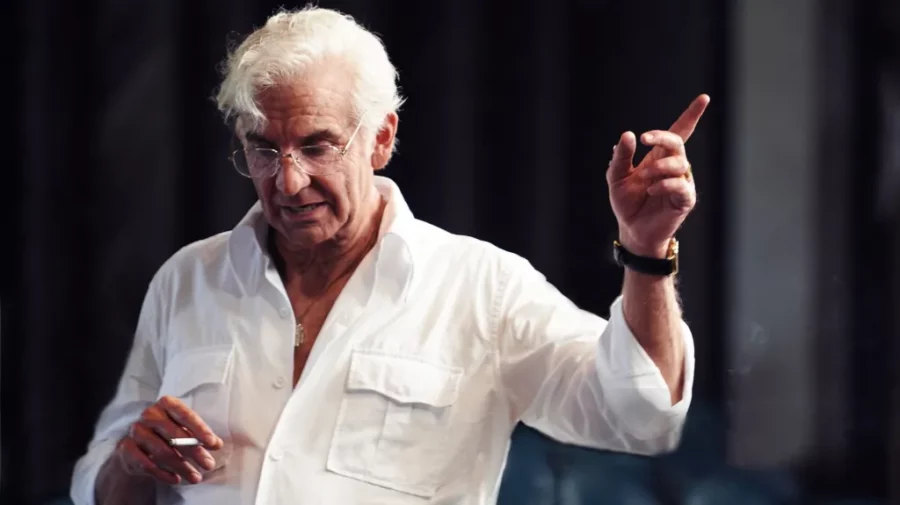

As a director Cooper is a showman, building terrifically cinematic, conceptual sequences designed for the big screen (see Maestro theatrically rather than waiting for its Netflix premiere), seamlessly integrating shot selection, camera tracking and editing, including a rushing early moment where Lenny springs from bed to the stage in what appears to be a matter of seconds, his apartment stairs blending with the theater’s house. Another finds young Felicia wishing to know more about Lenny’s personal life, upon which he whisks her, seated, onto an empty stage where she suddenly finds herself surrounded by men costumed as sailors in an On the Town production, revealing both his orientation and artistry before pulling her directly into it. Later, Cooper brings down the house in a six-minute conducting feat of Mahler’s second symphony, set in 1976 at Ely Cathedral and recorded live with the London Symphony Orchestra, ending on a sublime camera pullback and revelation that delivers the picture’s thesis—through art, fire and pain, love endures. Each of these audaciously crafted sequences, using the formal elements of film to conceptual narrative propulsion suggest, given the shortage of visionary filmmakers working today, a nearly extinct brand of artistry in American film.

While the 1980s-set late scenes in the film convey both Bernstein’s genius and sadness, Cooper (who believably ages decades through terrific makeup) positively excels in an on-camera interview device that reveals both Bernstein’s richly passionate love for music and people as well as deep fear of being alone. Mulligan, in a performance that had those in my screening audience weeping, pulls out the stops, flooding the film with kindness of heart and an ebullient pathos unmatched by any other actress this year.

While some may focus on what Maestro isn’t—a deep dive into musical history or studied portrait of an artist—those who follow Cooper and Mulligan into the deep end of their intelligently performed love story will be rewarded with the best movie portrait of marriage in ages.

3 1/2 stars

Love your review. I could clearly feel the emotion in the scenes you described so beautifully. I wan to see this movie and experience the emotions of this couple. It is apparent that this project was a labor of love for Mr. Cooper. How amazing that he conducted an entire orchestra for a major movie highlight. I love your review !

Hi Joanne- Thanks for this great comment and glad you enjoyed the review! Cooper has crafted quite a captivating love story and one wrapped up in a stylistically bold movie, and both actors (particularly Mulligan) are unmatched this year in terms of emotional investment. I can’t wait to hear from you once you have seen the film! -Lee