I ventured into Saw X armed with only the faintest recollections of its inaugural 2004 original, which saw the light of day almost two decades ago at a time when the American horror film arena indulged in notions of “torture porn”—a subgenre in which extreme suffering and dismemberment in close-up were de rigueur. Such brutality ruled the day, often ingeniously constructed (The Human Centipede), deeply mean spirited (The Devil’s Rejects) and, on occasion, diablolicly entertaining (Hostel).

With an absence of social commentary and relentless focus on bodily mutilation, such down and dirty works of mayhem could, perhaps, be traced back to Pasolini’s revered and reviled 1975 fascist parable of barbaric excess Salo, or the 120 Days of Sodom, the ultimate enter-at-your-own-risk proposition which found an assortment of Italian teens subjected to a roundelay of cruel exploitations with allusions to both Mussolini’s regime and the Marquis de Sade himself, the picture’s purported inspiration.

By nature, torture porn movie excursions have little to with conventional notions of what an effective horror film can do—primarily scare you silly—and rely neither on suspense building or addressing primary audience fears (the dark, the boogeyman, etc.), instead parading gore and suffering in the extreme, gawking at the degradation of the physical self.

This primal body horror can also run a gamut of subject matters, served up as entertainment as in the anthropophagite Amazon jungles of Ruggero Deodato’s 1980 cult epic Cannibal Holocaust, a faux documentary so convincing it found the director hauled into court on charges of animal torture and suspicion of making a snuff picture, or, bizarrely, as spiritual edification in Mel Gibson’s explicit 2004 evangelical saga The Passion of the Christ, depicting the redeemer’s final trials in a lingering, luridly brutal glory as vicious as any picture in the genre.

Today, the horror film is two decades on from such explicit excursions, straddling low-rent supernatural seat fillers (The Pope’s Exorcist, The Nun II), exhausted franchises (Halloween reboots, The Conjuring universe), high concept “elevated” thrills (The Witch, Hereditary, The Babadook) and the occasional smart sleeper (Smile, Talk to Me). Consistently the most profitable genre, made on the cheap and able to garner loyal, always-show-up audiences, for moviegoers being scared out of their wits remains big box office bank.

Saw X, this week’s horror offering in a season that seems to open a thriller every other week, is a curio, at once a throwback to an era of extreme gore all but vanished from the mainstream but a picture that has more on its mind than mere carnage. Its horror elements may be transgressive but it manages, for awhile at least, to achieve a measure of substance both unexpected and welcome.

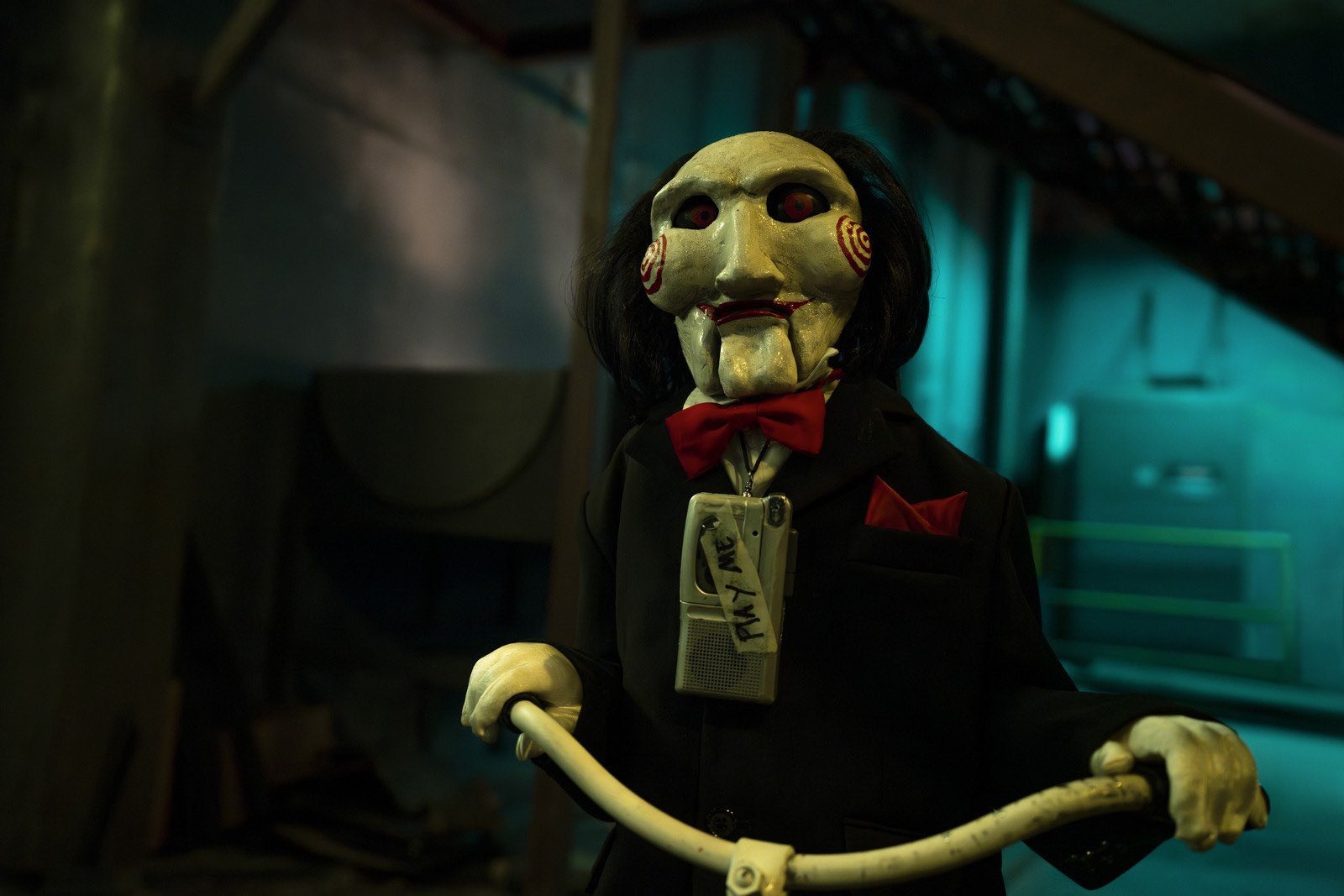

For the uninitiated, Saw began in 2004 as the brainchild of star Leigh Whannel, who wrote the screenplay, and director James Wan, a formidable collaboration that would later yield two more Saw installments and launch the Insidious series. That picture found two strangers waking up in a mysterious room, ordered by an omniscient puppeteer to play elaborate survival games as a morality play comeuppance. It was a simple, blunt force picture that introduced us to a new movie villain, the Jigsaw Killer, in reality a former engineer and cancer patient named John Kramer played by Tobin Bell as a sort of sadistic, avenging angel holding the morally bankrupt in contempt of their transgressions, forced into a devil’s bargain as atonement.

Ten films and nineteen years later, new chapter Saw X moves back in time to somewhere between the first and second film, and with sincerity spends thirty or so opening minutes of its 118-minute running time building a compelling psychological portrait of the cancer-stricken Kramer, which star Bell is more than up to, facing mortality with a haunted gravitas.

With mere months to live, a tip on an experimental miracle treatment leads Kramer to an undisclosed Mexico location (we are informed that “big pharma” is on the trail) where a too-good-to-be-true procedure renders him immediately cancer free. Bell invests this extend setup with such feeling and subtlety—yes, in a Saw movie—that you half expect the movie might veer from its sadistic series schematic.

But not so. The perpetrator of this depraved ruse is a cool European blonde named Dr. Cecilia Pederson (very well played by the estimable Synnove Macody Lund, notable Norwiegan actress, author and filmmaker), doling out credible medical diagnoses with endearing bedside manner before absconding with hundreds of thousands in cash sans any real treatment. This major ethical lapse will be addressed full-tilt once Kramer gets wind of it, the picture kicking into high gear.

What follows is what the Saw audience shows up for, its typical tribunal of blood and guts as Pederson and a merry band of Mexican opportunists (Joshua Okamoto, Paulette Hernandez, Octavio Hinojosa, Renata Vaca), each hired to pose as kindly caretakers and credentialed surgeons, find themselves on the receiving end of Kramer’s extravagantly designed mayhem over a very long night of the usual elaborate puzzles and deathtraps. Saw off a leg to avoid a decapitation? Check. Extract one’s own brain matter? Check. Such extreme horror sequences are undeniably well-staged if, at this point, familiar. Forget considerations of how such intricately inventive machinery could be so quickly and expertly built and installed. Not worth worrying about.

Along for the ride is Kramer’s henchman Amanda (Shawnee Smith, in a bad wig), who corrals the potential victims but also displays a modicum of sympathy, a voice of almost reason foil to Kramer’s singleminded quest. And so it goes—death, philosophical debates, victims pleading for their lives, blood and more blood (small intestines prove handy in a pinch).

Saw X is an unusual beast, initially absorbing but the same primal animal underneath. In truth it is strange to identify with such a flawed “protagonist,” presented as having the strongest moral compass onscreen despite his predilection for visceral punishments that hardly fit the crimes. As directed by Kevin Greutert (a longtime series editor on his third series outing as director), the picture looks great, is madly efficient and more substantive than previous installments.

Still, one never really knows whom to root for in a Saw movie—the terrified victims or the method-to-his-madness, cool customer killer, who here is written with greater heft. Given the amount of human trauma onscreen, I found myself wishing that most of his victims would solve their way out and escape; with the exception of perhaps Pederson, the make-a-buck Mexican minions hardly deserve their fates.

Ultimately, what should we make of a film series for which the calling card is, mostly, extended torture minus genuine scares or suspense, that deals with its antiheroic villain’s mortality with poignancy, humanizing him (he even sincerely befriends a young local boy who figures gruesomely in the picture’s climax) while his disposable victims’ mortality is presented as par for the course punishment?

Saw X doesn’t address Kramer’s pathology, which is presented as justifiable; he is not a purely evil man but one with a severe, Old Testament world view of crime and punishment, playing God at will and without contemplation. If the screenplay, by Josh Stolberg and Pete Goldfinger, has enough integrity to present him with substance and humanity as he faces terminal illness, why not with a bit of self-awareness about his extracurriculars as well? Undoubtedly such considerations are irrelevant in a movie that accomplishes what it intends—a bit of substance and pathos, a lot of bloody retribution and exactly what its audience wants.

And I couldn’t look away from the “blood waterboarding” finale, which in a Saw film is all that really matters.

2 1/2 stars