Christopher Nolan’s A-bomb opus Oppenheimer is a dense, often accomplished and sometimes portentous character study that both intrigues and alienates in its study of the birth of the Atomic Age and mastermind physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer’s (Cillian Murphy) WWII-era race to complete the world’s first nuclear weapon, after which he faces a personal and professional reckoning over his creation’s spoils. In telling this multilayered, ambitious story, Nolan has delivered an adult-level film that brims with ideas and signature command. Yet despite its weighty subject and obvious craft, Oppenheimer has curiously muted dramatic impact.

Based on the 2006 book American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer by Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin, Nolan has fashioned a multi-narrative, era hopping picture, a character study of the “father of the atomic bomb” with an excess of story agendas spanning from 1924 to 1963, crosscut for nearly the entirety of the picture’s 180-minute running time. As this is a Nolan film, byzantine structural labyrinths are prized; humans not so much.

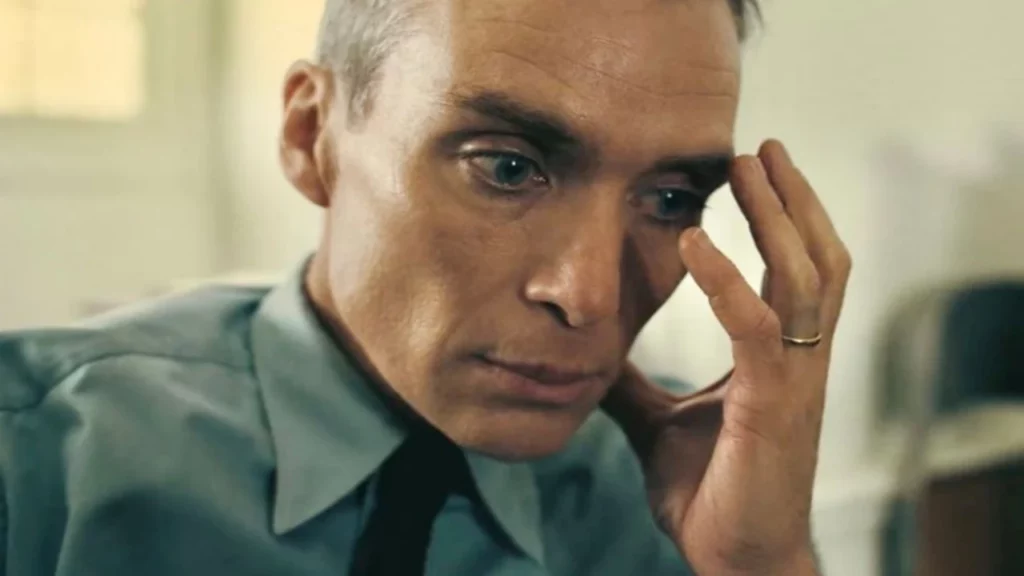

The fine Irish actor and Nolan regular Cillian Murphy plays the brilliant theoretical physicist, whom we meet early as frustrated Cambridge collegiate before going on to an academic career at Berkeley circa 1930s, during which he meets two very pivotal women, the passionate but mentally unbalanced Jean Tatlock (an underused Florence Pugh), with whom he has a years long affair, and the married Kitty (Emily Blunt), who gets pregnant, divorced and then unhappily married to Oppenheimer, a relationship Nolan undernourishes.

Enter The Manhattan Project, to which Oppenheimer is recruited by project director and Army Corps of Engineers officer Leslie Groves (Matt Damon). The nuclear race suddenly on, Nolan charts the advances of Oppenheimer’s extended team working diligently in their clandestine Los Alamos laboratory as a ticking clock competition against the Russians and Nazis. Such efforts culminate in the famous 1945 Trinity “Gadget” desert test plutonium detonation, which Nolan mounts sans CGI as a blinding flash of heat and light and cloud; the technique is undeniably accomplished.

At about the two-hour point, Fat Man and Little Boy are infamously dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945, effectively ending World War II (but ironically beginning the age of nuclear proliferation), and Nolan’s slavish adherence to Oppenheimer’s point of view means that the picture withholds witness to the devastating fruits of his labors; Japanese destruction is not depicted. Instead, Nolan emphasizes Oppenheimer’s post-apocalyptic moral dilemma, a guilt expressed in a superb, surreal sequence that finds the reluctant “American hero” speaking to an excited crowd of Manhattan Project teammates. This passage, with its nightmarish renderings ripped from Oppenheimer’s imaginings, is the picture’s bravura visual apex.

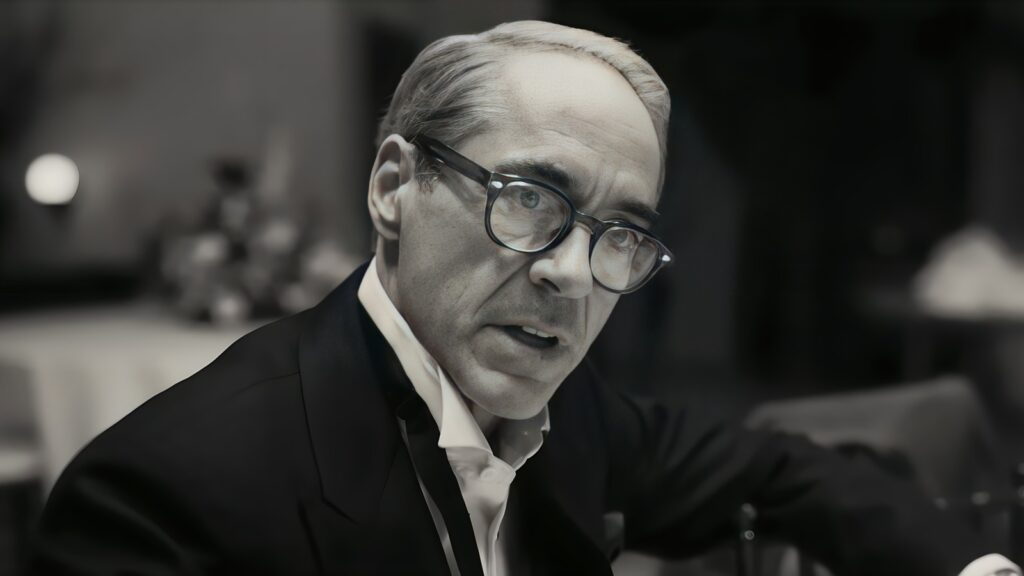

Nolan weaves in dozens of primary and peripheral characters, including a very good Robert Downey Jr. in a major dramatic return as U.S. Atomic Energy Commission chair Lewis Strauss of Princeton’s Institute for Advanced Study, who recruits Oppenheimer as the program’s director before a humiliating public fallout. Nolan gives significant running time—too much—to Salieri-esque Strauss’ black-and-white shot, 1959 Senate confirmation hearings, providing a very good Alden Ehrenreich, as physicist Richard Feynman, with an effectively humorous interjection, while Rami Malek enters the picture for a brief testimonial, his role feeling truncated from a larger whole.

Yet another substantial section of the film deals with Oppenheimer’s 1954 security clearance hearing where efforts to revoke his access include Jason Clarke as special counsel to the Atomic Energy Commission, tasked with interrogating Oppenheimer, Kitty and a host of others in a claustrophobic, closed-door tribunal. This section, as well as the Senate confirmation hearings, are returned to over and over (and over) during the picture’s run time, woven together with the real-time Los Alamos bomb building and papered over with a far too-loud, too present score by Ludwig Göransson.

There is more, and more in this minimalist film dressed up as maximalist American history, including the fine David Dastmalchian in a brief but impactful role as William Borden, executive director of the U.S. Congress Joint Committee on Atomic Energy, who raises suspicions that Oppenheimer just might be a communist security threat. Did I mention Albert Einstein (Tom Conti) turns up as Oppenheimer’s confidant and friend? Even Harry S. Truman (Gary Oldman, under makeup again) appears in a tense Oval Office meeting during which Oppenheimer confesses that he has “blood on his hands” before the hardline president admonishes him a “crybaby scientist.”

By Nolan’s hand, J. Robert Oppenheimer is not just an American Prometheus but a Shakespearean figure—flawed, ambitious, isolated, plagued by internal conflict and ultimately betrayed—whose rise and fall as depicted here is political, historical, cultural and personal. Through these lenses there is history and substance here but the film itself is often detached, told largely as an overdetermined montage, liberally shuttling between multiple events and time frames, rarely allowing a scene to build or play out uninterrupted. Such rapid-fire editing tempers the already busy narrative’s impact. Still, while verbose and assembled to its dramatic detriment, in its best moments Oppenheimer manages to convey a shattering sonic boom of regret, courtesy of the haunted Murphy.

While Nolan has assembled a massive, high bar acting ensemble, both of his actresses are given dramatic short shrift, Pugh delivering her emotional, carnal all as the tormented Tatlock but hamstrung by a too-brief appearance. Similarly, Blunt is out of narrative focus for much of the film, sidelined until a final reel interrogation ranking as perhaps the film’s most emotionally direct.

Film purist and preservationist Nolan, ever the cineaste whose pictures are shot on film and often in multiple aspect ratios most suitable for IMAX presentation, has as per usual struck 70mm prints for special theatrical exhibition. However, the pre-opening print I saw looked as if it had been running for a good few weeks, replete with dust and occasional scratches.

While Oppenheimer has a clarity of vision and technique to admire, Nolan has made one of his least engaging films. Intelligent, thorough, well-researched and acted, is also an arduous endurance test given the amount of talk in the picture’s first two hours, largely consisting of men in rooms debating science and not always in fully accessible terms. This makes the film sag in points, becoming the quintessential violation of the “show don’t tell” screen axiom; there is a lot of telling here.

Considering a career canon that includes such pictures as Memento, The Prestige, The Dark Knight, Interstellar, Dunkirk and Tenet, the extent to which each land on the audience is a Rorschach test for whether viewers have a stronger desire for the human experience, engagement and catharsis, or are happy to submit to Nolan’s cerebral, sometimes detached puzzles. Perhaps those familiar with the source material will find deeper engagement with Nolan’s vision, but many will exit Oppenheimer wishing they had experienced a stronger connection to its people than its filmmaker.

The end result of this impeccably mounted picture is one of something reaching for greatness but somewhat hindered by a heavy directorial hand—too much crosscutting, too much music, too many time frames at once and too little reflection until its final, strongest act. Sometimes a great story is a great story and can be told at face value, and the events of Oppenheimer’s story are epic enough that such directorial fussiness inadvertently diminishes them. No doubt this will be an unpopular opinion as much of the effusive critical discourse around Oppenheimer, currently awash in superlatives, suggests it a masterpiece.

In truth, it is a challenging experience with middling returns.

2 1/2 stars

Thank god I am finally seeing a less-than-gushing review for this! I would shave off a half-star. The performances are largely very good and there are some moments of interesting cinematic technique, but I haven’t loved a Nolan film since “The Prestige” and it is now clear he has fully embraced bombast and often needless narrative structure showiness and is worlds away from he filmmaker who made “Memento.” This plays like a 3-hour trailer for me. No scene gets a chance to breathe and the incessant musical score (is there more than 5 minutes without music in this film?) drove me utterly batty. And you are right on target with your comments on the securing clearance hearing and Senate confirmation vote. In a movie that addresses global existentialist issues and one man’s personal demons, Nolan decides Oppenheimer’s professional reputation is the big stakes here. Seriously? Widly overrated film. And while I love that Nolan is helping keep actual film alive, the multiple formats for this film — and the fact that he adjusts the aspect ratio for specific formats — indicate what may be the biggest problem for Nolan: he’s become more technician than artist, to the point where he can’t even decide on a universal look for his movie.

As an aside, while I am thrilled for theaters with the success of this and “Barbie” (and very much looking forward to the latter), the premium movie experience is not a great long-term recipe for the continuation of the theatrical movie-going experience. Only a handful of movies will get this kind of box office at premium prices.

Sorry — a couple of typos above, including what should have been “security clearance.” Typing too fast in my frustration! 🙂

Hi Joel, Great to hear that we are of like minds here; it’s lonely on this front at the moment. I am in full agreement with your assessment above. The film’s trailer-like cutting accompanied by its way overused score left me exhausted. The abundance of Fuss Directorial Technique left me at a cold, distant proximity to the narrative, which was already too complex for its own good.

On the security clearance and Senate confirmation sections, did we really need to continue returning to them over and over across the three hours? Was there that much useful narrative wrapped up in those episodes? Nothing revelatory happens in either.

And I would agree on Nolan’s focus with technique and form. On the one hand, good on him; I’m a 35mm collector myself and avidly seek out exhibitions of projected vintage films. On the other hand, give me the high-bar experience of Dolby Cinema any day for new releases.

I suppose I would also say that in all of Nolan’s films there has not been a single character I have found that compelling, at least as written. Sometimes the actors manage substance and emotion but rarely does it come from the page. After awhile, for me at least, there are diminishing returns to pictures that are byzantine riddles in structure and story.

On (what could have been) the central issue of nuclear proliferation and its existential impact on humankind, the film does not wrestle this to the ground despite a conversation with Einstein and the clear misgivings Oppenheimer feels after his creation has been weaponized to mass destruction. But in the run up to finalizing the bombs, what did he think would be the end result? That the bombs worked as planned in their annihilation was somehow a shock?

On the half-star issue, I revised as I had originally felt it was a 2-star film but in my “hive mind” anxiety while writing, and anxiety over its pedigree, had initially upped it.

Great to connect here. -Lee