Albert Serra’s haunting post-colonial epic Pacifiction begins and ends with a skiff of French marines arriving, then departing a Tahitian island. Their intentions in this place, eventually revealed across a languorously paced picture with a meticulous insinuation of dread, may or may not be geopolitical strategem. The film, a 162-minute test of audience endurance rendered in an oblique, just-out-of-reach narrative style, is a low-key examination of hushed political maneuvering with intriguing Tahitian cultural observations and a terrific star turn from the great Benoît Magimel.

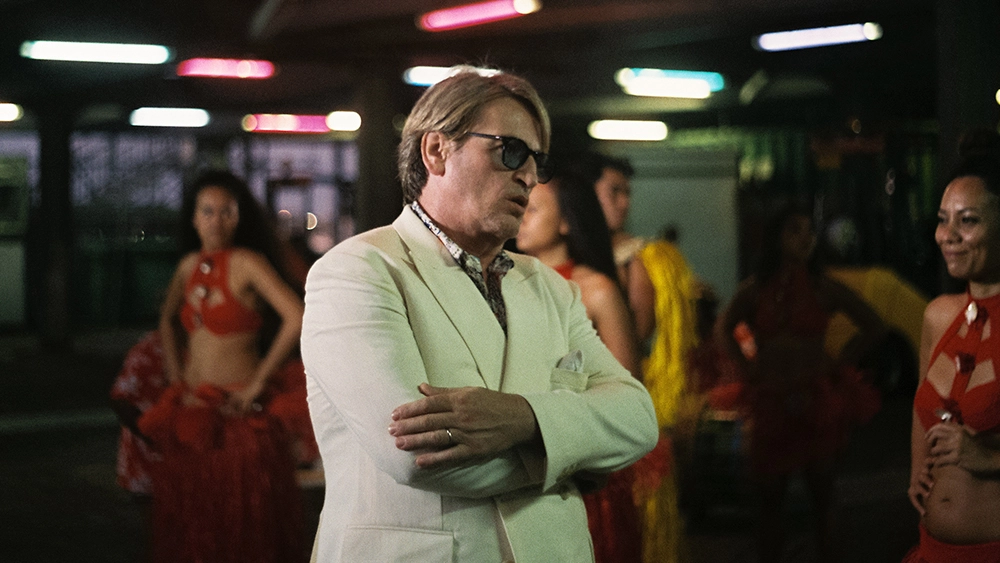

Magimel stars as the white-suited De Roller, the High Commissioner to France who resides on the islands and carries a rumpled, elegance in decline charm of a Grahame Greene protagonist, an ambassador of diplomacy whose better days and influence are perhaps behind him. His Tahiti, presented here as lushly as French Polynesia has looked onscreen since 1984’s The Bounty, is caught in a schism between increasing governmental autonomy and the closed fist of old world French rule, a tropical paradise ensnared in political subterfuge and on the brink of something shadowy brewing beneath.

De Roller is quite an invention, a sort of affable overseer, longtime embedded with the locals and with an amiable reputation; he’s earned the trust and confidence of the Tahitians. He frequents the local bar each night with its owner (Sergi Lopez), a place appearing to be the only game in town and one with exotic dancers carrying on tribal traditions for flush tourists in a place suggesting couplings of all kinds, including transactional. He’s a smooth operator and a longtime fixture, a governmental go-between whose empathies, in the twilight days of his assignment, are tilted toward the locals as if an honorary member; he even advises them on the accuracies of an indigenous dance.

De Roller is also savvy with the coming-and-going officers and bureaucrats circling the island, and for the picture’s first hour, is embroiled in a series of coded and sometimes clandestine conversations, including those with a mysterious admiral (Marc Sussini) who may be planning a return to military testing on the island, an anxiety felt by the local populations, poisoned a half century earlier by similar military maneuvers. This rising fear is bolstered by the appearance of a submarine lurking offshore.

This submarine and its inhabitants, frequented nightly by local prostitutes, as well as the sudden appearance of men in uniform, have the islanders and the increasingly distrustful De Roller on edge. In one terrific scene, De Roller meets with a group of island representatives who push him to reveal the nature of the military presence, suggesting a local uprising and clash are bound to ensue should any aggression be on order.

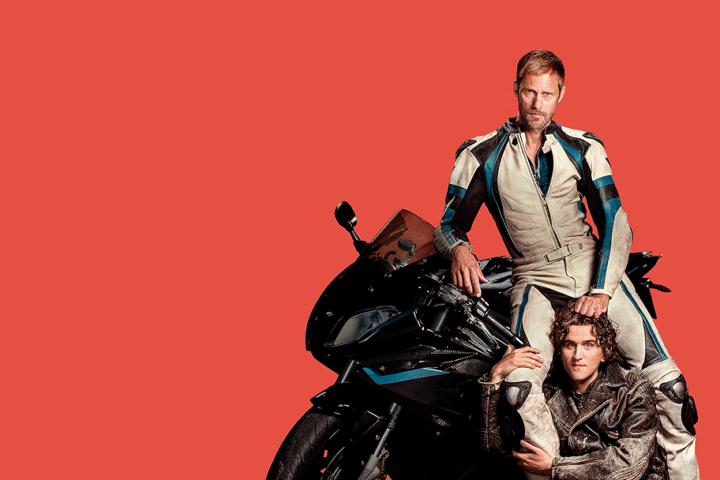

Amidst the roiling tensions is a fascinating character named Shannah, played by a marvelously expressive and enticing trans actress named Pahoa Mahagafanau, a hotel employee who serves as the club’s choreographer but also as a likely lover to De Roller; they are so electric together one wishes Serra had given their union more screen time. Shannah is also of interest to a mysterious Portuguese diplomat (Alexandre Melo) whose passport comes up missing. Mahagafanau, holding the camera in close-up each moment onscreen, is a born movie star and terrific scene partner with her famous French movie star counterpart (who won the Cesar for this very performance).

What may sound like a heady amount of plotting for a political thriller, but Pacifiction is unconcerned with such mechanics, instead content to languish in its Polynesian atmosphere, exploited to the hilt by cinematographer Artu Tort, using three Canon Black Magic Pocket Cinema cameras to capture richly saturated foliage greens, crystal blue seas, neon-bathed nightclubs and inky, ominous midnight skies, which prove foreboding in the picture’s eerie denouement. With similar innovation, Serra’s use of improvisation in liberal passages of dialogue (including the use of an earpiece for Magimel during some lengthy political monologues) suggests a moment-to-moment unfolding onscreen; never once does the picture feel scripted or didactic in its often extensive dialogue.

Despite inherent tension in its haze of bureaucracy, paranoia and a potentially coming apocalypse, Pacifiction offers little crescendo, dramatic payoff or catharsis. Yet in the picture’s final moments, Serra’s hypnotic rhythms suggest an inexorable fatalism. For many, Serra’s deliberate, methodical picture will fail to engage. Yet for those who stick with its sometimes lulling, ultimately engrossing currents, the rewards are plenty.

3 1/2 stars