Exquisitely observed and deeply felt, Lukas Dhont’s Cannes Grand Prix winner Close is an adolescent coming-of-age picture told with such heartstopping sensitivity that it instantly ranks amongst the best films ever made about childhood loss—that of our friendships, our innocence and, sometimes, those we hold most dear.

Charting the delicate, idyllic union between two thirteen-year-old Belgian boys (the unforgettable Eden Dambrine and Gustav de Waele) that will be shattered by inevitable intrusions of peer pressure and social conformity, Dhont imagines a utopian, carefree world of protective brotherhood—and perhaps of potential first love, too early to be articulated—and then forever fractures this equilibrium. The severance is made thrillingly poignant by never-acted-before star Dambrine, who carries the weight of guilt, and the world, on his young shoulders, holding the camera in close-up with preternatural poise.

Writer-director Dhont, the thirty-one-year-old Ghent-born filmmaker educated at Belgium’s Royal Academy of Fine Arts whose equally sharp-eyed debut Girl took Cannes’ Caméra d’Or in 2018, made the Forbes 30 Under 30 Europe tally in 2019 and has, with Close, proven that his freshman film success was no mere fluke. Nominated last week for this year’s Best International Feature Film Oscar, his Close is a masterful, humanist reminder of cinema’s power to confront and dismantle established norms with heroic authenticity. As an artist, Dhont does so with immense compassion for his young actors, their characters and his audience.

I recently caught up with Lukas Dhont for a chat at Chicago’s Four Seasons hotel, and in an unusually substantive conversation—as anyone who has seen his films might expect—Dhont was rich with abundant observations on adolescent fragility, his filmmaking processes and his artistic drive to address taboos in his pictures.

Lee Shoquist: Close is euphoric but also deeply painful. It sits in the intersection of many different life experiences, including friendship, perhaps love, coming of age, peer pressure and family relationships. It beautifully illustrates that undefinable adolescent moment when you have all of these strong feelings yet do not quite know what to do with them.

It would be great to hear a bit about capturing this state of being between your young actors, Eden Dambrine and Gustav de Waele, particularly in the lyrical first part of the film, which suggests a Garden of Eden utopia in its freedom, sensuous use of nature, color saturation, music and feeling.

Lukas Dhont: Yes! This Garden of Eden concept is very interesting given that my main actor is named Eden. I have these vivid memories from childhood in which the love I felt in my friendships seemed boundless in the sense that there didn’t seem to be any frontiers or any names. It was just very free. And I think many of us have felt these connections in childhood that are incredibly strong and pure. When we are young there is this clinging or holding onto one another that we somehow lose as we get older. Society often separates us and tears us apart.

Categorizes us as well.

Yes, categorizes us and also throws things at us, and we often feel like that connectedness is not validated as much as it should be. When I was determining the dramaturgy of this film I realized that I really wanted to start in young friendship and connection because—especially between two young boys—we so rarely point the camera at it. We have often pointed the camera on the battlefield and on men fighting wars with each other, but the presence of these images—of two young boys laying together in a bed as close as possible—I knew that they were exotic, and even though we have all been there and laid in that bed, we are not always invited to see that.

Do you mean exotic in the sense that they may strike that reaction in the viewer?

Yes. I know we are conditioned to immediately look at that as something sexualized because we are just so not used to seeing it. I wanted to speak to that moment in time. I also knew that the first part of the film, the first 15 minutes of the two boys clinging together, would always be too short; that it would never be long enough because it is something that we sometimes wish that we could return to, and that there would be this moment in time that this new consciousness would slip in and change that relationship; that one of them would suddenly start to look at it differently, through the perspective of a society that labels and divides and has its norms and expectations for us. So I really wanted to find the dramaturgy in which that was possible.

Although very different from each other, they gravitated together like magnets and there was an immediate closeness.

With these two young men, I found one on a train and the other because we scouted all of the schools in and around Brussels. We saw many young, talented people, but they stood out for us because even though they had never met before, when they did there was this accidental physicality and chemistry. It was not forced. Although very different from each other, they gravitated together like magnets and there was an immediate closeness. That was one of the things that we were very intrigued by, because the film is so much about physicality and intimacy, or the loss of those things, that we needed to find two young men with which that would be possible.

And I love working with this age because I find that if we listen to them they remind us of this very pure essence and connection to the heart which we often lose because we start to speak like society wants us to or we get conditioned to think in certain ways to feel accepted. And so they still have that. I also found that the way they talked about the script and their roles actually really helped shape the film. While the framework and elements were there, they really became co-authors of this piece.

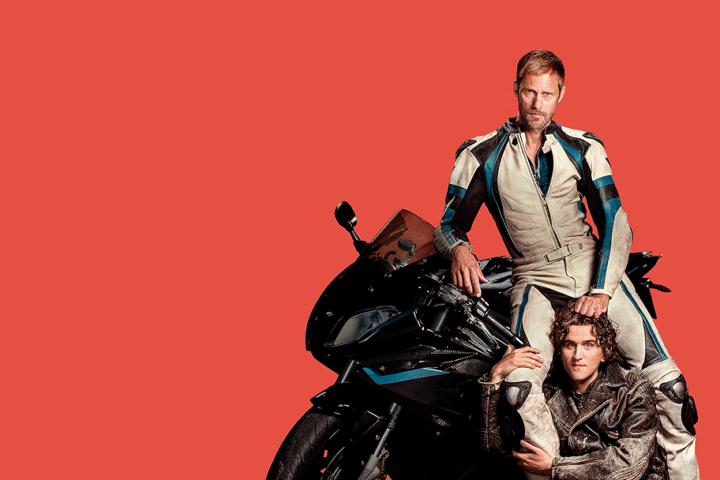

The embrace between them in the film’s poster image is one of enveloping protectiveness. It’s almost a physical representation of what you mentioned; not wanting to let go of that pure connection.

Yes! I always envisioned the poster being that idea of holding on to someone. And then also I think because in the second part of the film there is another, metaphysical theme: can someone be close even if they are gone or not there anymore? So I felt there was also a mystery to that. One of them we see while one becomes a sort of a memory. Because you do not see his face it becomes an abstract element. I felt it was very layered to have one boy looking at us and another whose face we cannot see.

The very first title of this project was We Two Boys Together Clinging, based on a Walt Whitman poem that then became a David Hockney painting, and I like that phrase because I feel like if we present that state of enormous togetherness, of being one, there is a breaking point where society will question the closeness between these two human beings.

there is a breaking point where society will question the closeness between these two human beings.

In terms of directing young actors to the level of emotion required in this film, particularly with Eden in the second half where he must carry so much weight—for example, the way he looks at Émilie Dequenne when she visits his hockey practice or when he sees her at the music recital or in the hospital—is it possible to direct that quality? And if so, how do you elicit this with a child of that age?

I think it is possible to direct that but a lot of the directing of those moments happens before the shoot. The way I rehearsed was to work for six months with these young people because they had never acted before, nor had they ever been in front of a camera. And there are many things that happened during those six months. I have to name them in order to arrive at telling you how we achieved that performance.

They had read the script once at the very beginning of the process and we talked about it very openly, but I asked them to never read it again. Because what I wanted to avoid was having them think that they must copy the words that were on the page. What we wanted, of course, was for the document to be a starting point but not the end result. They loved that because they realized they would not have to learn any text; they have to memorize many things in school and in many ways it limits their creativity. What I wanted was for their creativity to shine bright. So I told them to forget about it.

And we spent time together and made a lot of pancakes because they love that, and we watched their favorite movies—Gustav loves Singin’ in the Rain, so thank God he had taste and it was not another! So that was fun. And as we very informally went walking by the seaside—and I’m not sure if they really realized what was happening—I asked them, “Why do you think Leo does not wait for Remy (in that scene)?” I did not give them my answer, but I let them make up theirs.

And what happened is that they became very active in discovering their roles. They became the shapers and detectives of their characters. And they loved that because their creativity was very much sparked. I brought in a camera after the first month and that camera would film us as we spent time together. What I wanted to achieve was for the camera to become an extension of our togetherness, and that when the camera was rolling I would not ask them to do anything differently. So they got very used to the camera. When we started shooting, the camera was merely an object that they had come to know and there was a transparency.

Léa (Drucker), who plays Eden’s mother, asked me how I envisioned the collaboration. I said it was very simple: “I need you to love Eden.”

I tried to build a family and intimacy. On the first day of rehearsals Léa (Drucker), who plays Eden’s mother, asked me how I envisioned the collaboration. I said it was very simple: “I need you to love Eden.” It is very basic, but it is very necessary. What happened is that we spent that time together and they got to know each other profoundly, building something that I cannot direct. I can direct other things, but I cannot direct that connection. So I know that in the scene when she comes onto that bus that bringing that news will be hard for her because she has fallen in love with this boy.

And what a great moment that is when she turns away from the camera.

Yes. I would never have been able to arrive at that moment if we hadn’t built the intimacy and the family between them. The scene, and the direction of it, happened as much before the shoot as during. So it was the same with the boys as they had built that connection and bond so strongly that I knew during shooting that they would rely on each other to arrive sometimes at joy, at beauty, at laughter, but also at this profound sadness. And then of course we also stepped out of that quite quickly since it was a shoot and also fiction, but it was about those layers that permitted them to go there.

A visit to your former junior high school became the impetus for this film. You must have plugged into memories. Was there a person for you like this, when you were growing up as an adolescent? And what do you remember about that?

Yes. I remember those days when there was this physicality and closeness, and I also remember that very precise day when consciousness slipped in and fear took a hold of it. I think what happened was that I started to push that person away, even though I think that person desired to stay close. So it was me pushing away. Something very brutal happens on the inside when we come to fear and therefore betray ourselves and the people we love. And I feel like I had not really seen that dynamic purely expressed in anything.

Something very brutal happens on the inside when we come to fear and therefore betray ourselves and the people we love.

I remember at that age that I had an adolescent friend and in private—never in public—we would sometimes hold hands. We never discussed it. I heard he eventually got married and had a family. Sometimes I wonder if he shares the same private memory.

Yes! I think we live in this culture and society that tells young men, as they are growing up, that that intimacy is to be kept hidden. We are very oriented toward finding romantic relationships but finding intimacy between and with other men is something that we do not validate.

Do you think this is changing with the emergence of the younger generation? They seem to have such an acceptance and fluidity around these things.

It is a hard question for me. It is a very hard one. How do I answer that? Do I answer from the positive side, where I think that I see so many young people trying to change and break down these invisible walls and deconstruct the patriarchy that has forced us to limit ourselves? Or do I confront the fact that six days ago a thirteen-year-old boy in France committed suicide? And suicide, of course we cannot equate to an A + B = C, but we do know that he was gay and repeatedly bullied at school. So I am split between those two things, and I cannot give you an answer on this because I do not know. I do know that these walls have been constructed for us over a long period of time and taking them down takes time and energy and repeated reminding of just how fragile our identities can be.

At one juncture in Close there is a bit of a shock. There were similar moments in Girl, your last film, and maybe a feeling at the time, for some groups, that they were too visceral, even though they came directly from someone’s real life story. Was that notion on your mind during the making of this film? To handle that sort of moment sensitively given the real-life implications of what we’ve just talked about?

Yes, but I think there is a question central to my life and work that I have tried to answer—and have not maybe answered fully, but I am trying to—and that question is how to confront violence and speak of violence without being violent. This, of course, is a question we could debate for a long time and one on which everyone has an opinion.

And with Close, we desired to have such violence off screen and yet also to talk about it. There are things that you understand and there are things that you do not. It is not completely true what I am about to say—because I do understand why I want to talk of it—but there are things bigger than you that you have to confront. There is a drive that takes over your body, and even if you wonder whether you should go there, you do.

There are things bigger than you that you have to confront. There is a drive that takes over your body, and even if you wonder whether you should go there, you do.

And for these two films, I think this idea of a brutality that turns inwards, and stops being directed to the other but instead changes its arrow to oneself, has been a need that took over for me. It’s like Nan Goldin recently said to me, “We have to destigmatize talking about suicide and mental health.” Maybe it is one of the things that I have tried to address in this film and at this time. At this moment we could look at statistics around (what happens when we) start to deprive young men from authentic connection and murder the beautiful friendships that they have—it is also the time when their suicide rates go up four times compared to that of girls.

So I feel that addressing taboos is something I need to do. I know that it’s a difficult topic and hard for us and that we wish it was not a part of our lives, but it is. And to me, staying silent on it and not speaking of it, or covering it up, is what really feels violent.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.