With features formed by a chisel and impeccably droll sophistication, Rupert Everett was, for a sustained run, a quintessential matinee idol whose visage thrust upon a forty-foot screen could remind one what movie stars could accomplish in their pictures, and us.

A striking combination of petulance (Another Country), swagger (Dance with a Stranger), suaveness (An Ideal Husband) and wry humor (Shakespeare in Love), Everett would have made an ideal James Bond, but Hollywood had other ideas. We’ll get to that in a moment.

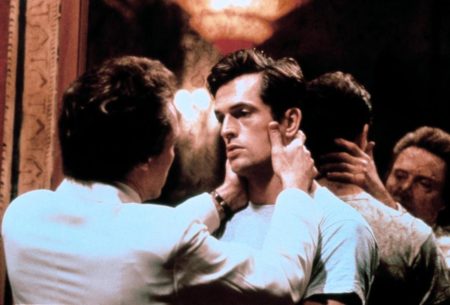

Indeed the young Brit star’s bold early turns in the 80s and 90s as a mysterious romantic stranger in Chronicle of a Death Foretold, infamous spy Guy Burgess in Another Country, the recipient of Ruth Ellis’ fatal attraction in Dance with a Stranger and an exotic, coveted object of lust in The Comfort of Strangers signaled an unpredictably risky actor never content to merely lead with those impossibly good looks. And he could have.

Act two for Everett found the star touching down memorably (and reductively, as tends to happen with the best imports) in Hollywood, stealing the charming My Best Friend’s Wedding and the (far) less so The Next Best Thing, playing a variation on an accessory every woman of the time coveted: the dashing—and gay—best friend and personal relationship advisor, a plus-one arm candy and a too-witty-to-be-sentimental shoulder upon which to cry.

What Everett couldn’t have known was that while the American public was embracing his spirited movie turns, Hollywood casting directors were getting cold feet. His new movie persona, combined with his very public coming out, ushered in an era of studio rejection and all but complete career standstill. Unless, that is, he wanted to continue playing the effete sophisticate—he was offered countless—in routine romantic comedies for the remainder of his foreseeable career.

Of course, Everett has always been too damned good for such trivial typecasting, a fact never clearer than at this moment, his titanic portrait of a late life Oscar Wilde drifting through memories of romanticism and regret ranking high on the shortlist of the year’s best.

The Happy Prince, a decade long project that he wrote, directed and in which he stars, finds Everett, like his narrative muse, reinventing himself with larger than life results. Wearing strategic prosthetics to approximate Wilde’s appearance, he’s both highly theatrical and intimately tender, a humanizing glimpse into a literary lion whose personal liberations, and loves, handily drove him from society bon vivant to tormented pariah. It’s a deeply compassionate performance coming from a place about which Everett knows a thing, or three.

I caught up with Rupert Everett recently to chat about The Happy Prince, some career high marks and the travails of his celebrated Hollywood stint, remembered as both a blessing and a curse.

What do you want to talk about that you haven’t been talking about all day?

Anything you want.

Let’s talk about the movie to start with, since that’s why we’re here. You were six years old when you were first read this story.

Yes, my mom read it to me when I was a kid.

But it didn’t crystallize for you until later, right?

It remained a very strong memory for me because I remember my mother and the story very well, and my relationship with my mother at the time was incredibly close and comfortable, and it was that wonderful time in life when kids don’t really have any idea or notion of problems. She was in her Jackie Onassis period with big white earrings, short hair and a minidress. And I didn’t know anything about all the subjects in the book because it is all about falling in love, suffering and the price of love and all these kinds of things. I don’t think I understood all of it and I’m sure my mother didn’t either, but we were transfixed by the story and in tears by the end. It’s something I’ve always remembered, and I think it changed my viewpoint a bit because I came from a fairly straight upbringing; quite militaristic and pre-Freudian. And I think it was one of the first things that made me think there was a whole other emotional vocabulary.

So when you say “pre-Freudian” I assume what you mean is that as an adolescent you wouldn’t have had any idea of the opportunities you might have to explore your own identity, even later.

Your own identity, just in terms of how you are feeling—all those things that had come to us in the 20th century hadn’t really come to my family, and I’m sure lots of families of the time. So that kind of talking or writing, which is all about love and emotion and the mystery of suffering—that kind of stuff really hadn’t occurred to me.

I have a feeling you find yourself kindred spirits with Oscar Wilde, in some sense.

I don’t know whether kindred spirits; for me, he’s someone who is almost like a patron saint or even a Christ figure in a way. He is someone I look up to in my own day to day struggles. I supposed embarking on or negotiating a career in the aggressively heterosexual, boys’ club world of show business you can’t fail to look at other gay characters and how they fared. And to me, Oscar is kind of the Christ of the gay movement. And in fact, the road to gay liberation started with the death of Oscar Wilde. It was very much not even a word—homosexuality—it all came about because of the debate that happened between the sexes around the world after Oscar Wilde. So he’s someone that has been very close to me. Also, coming to London as I did in 1975, it had only been legal to be gay for about seven years. So we were very much still walking in his legal footsteps.

It took you ten years to get this picture off the ground. Why so long?

Ten or eleven. Well, the first two and a half years were trying to find a director, and that was a very lengthy period. The agencies of Hollywood are fortresses that you can hardly get into if you are not in the right place at the right time. After two and a half years I managed to get ‘no’ from seven directors. And I thought, ‘I can’t go on like this forever.’ So I decided to direct the film myself, not really knowing what the problems were going to be. And the next seven years were me getting it together. The first three, nothing happened. And then I decided I would do a play about Oscar Wilde—playing him—and see if I could get some interest that way. And I got that together and we put the play on. But again, that takes a year to organize. But it did the trick. I got the BBC and Lionsgate to come on, and then little by little after that I managed to get the production up and running.

Seven directors passed? It seems to me that it’s a prestige picture right in the wheelhouse of what would be considered awards worthy, and really a boon to direct. What were you hearing?

I think probably nothing very macabre, really, but the kind of directors I was after were the ones who do their own things and had four or five things they were trying to get together. And it just was not what they wanted to do. So I don’t think it was a subject matter issue.

The Happy Prince moves fluidly between different time periods. It’s an interesting choice in how it assembles snapshots from Wilde’s life and it gains a cumulative power in doing so. I assume it was written as that structure rather than architected as such in the editing?

Yes, what I wanted the film to be about is a guy who is having a drink, going home, bumps into a woman who gives him five pounds, goes and spends the five pounds, falls off a table and dies. And the initial idea was that you could be going out for a drink on Friday night and a week later you were dead. I thought there was something very interesting about that. I was also very keen to show what it’s like when your brain starts closing down. Having watched my own dad’s death in close quarters, I noticed that it collapses like a cliff collapses—bits of it fall off, and as they do there are bubbles of memory. I could see with my dad that on occasion he was just somewhere else. So I had the idea of the ‘deathbed room,’ which for me is a very dramatic and fabulous room. You can see it in (Henry Wallis’ painting) The Death of Chatterton, and Napoleon and Byron; they all had these wonderful rooms. Wilde’s is a great one because it’s in this cheap hotel that smells of drains, with this awful wallpaper. And I wanted the room to expand and contract with his dying breath, so it would expand and he would suddenly find himself in another area of his life. And the brain, as it collapses—this probably sounds a bit wanky (laughs) but it’s what I was thinking—comes up with all these memories as if it’s putting all the books onto the bookshelf before going to bed. It graduated a little bit from there, but it’s the memories of a fevered brain.

Of the multitude of ways one might make a film about Oscar Wilde, you chose to focus largely on the final chapters of his life. Why this era?

For me, in the Christ scenario it’s the passion of Oscar Wilde; it’s the stations of the cross. And I wanted to write a film about that. I find the idea of him in this period wonderfully inspiring. He wasn’t really a victim. He carved his own way even if it was just to the street corner. He wrote his own constitution and he quite neatly replaced the royals and movie stars of his former life with street urchins and petty criminals of his new life. And he continued to be curious about things, have crushes, misbehave and scour the boulevards for rich people to fleece for drinks. In that I find that he is an amazingly inspiring character who keeps buggering on somehow, right until the last minute.

Pairing yourself with Colin Morgan was very effective. I liked him a great deal despite some of his own character issues with Wilde.

He’s an amazing actor and in real life he doesn’t look like that at all. He’s like an Irish boxer!

Right. After I saw the film I Googled him to see what he really looked like. You’ve made him something of a romantic dream in the movie, and it was quite a transformation.

He is one of the best actors of his generation in England. He has an amazing ear for dialect. He’s northern Irish and he has a completely different voice from the one he uses in our film. And once I put the blond wig on him his whole face changed into something else. It was one of the most amazing and exciting parts of the movie.

You gave him quite an entrance as well.

Yes, a great entrance.

It’s a lovely movie aesthetically. I assume it was done on a fairly low-budget but it has the sheen of a well-mounted period piece in its cinematography and score; there is a handsomeness across the board.

I worked in Italy a lot in the beginning of my career and it was one of my reinventions as an actor…

The Comfort of Strangers is one of my favorites…

There you go! That’s a perfect example. It was designed by a guy named Gianni Quaranta and he- that kind of aesthetic and texture in films—often from the 60s, 70s and 80s—is gone. I noticed all of those things while working on those films, and I wanted to bring them into my film, wanting it to be as textured and exotic and deep, in terms of aesthetic, as then. So what I had seen in all those films I’d been in was always on my mind.

Did you pick up anything from Michele Soavi?

Soavi as well had an amazing- his realization of a cartoon to film (Cemetery Man) I think is one of the most brilliant ones of all, much better than Dick Tracy, The Mask– it has a brilliant design integrity to it.

It has a cult of fans still today.

Yes, it’s a popular film! And rightfully so because it is a real work of art, I think. There is not a single digital effect in that movie.

Speaking of The Comfort of Strangers, I’ve always thought it was lusciously designed and mysterious. Even in conclusion it never plays all its cards. I doubt it would be made today. The style, mood and sinister atmosphere of Venice was so well-captured. There’s a scene at the beginning where you’re having dinner with Natasha Richardson and there’s a discussion of…

Elbows.

Yes! What do you remember about that film?

Well, it was the meeting of two great and very interesting people—Harold Pinter, who wrote it and Paul Schrader, who is a fascinating guy and a wonderful filmmaker. It’s the kind of film that just would never get made in a million years now because it just asks questions and there isn’t a single solution. But it is a movie I am very proud of; I loved working with Chris (Walken), Helen (Mirren) and Natasha. It is one of the movies that I remember with the most pleasure. I think it is so clever and well-written. Everyone always talks about the elbows.

What do you think about the industry now as opposed to the time you came up in the 80s? That was a much more closeted era. What is it like today for young actors and is there still a risk to do what you did? You were a trailblazer. Over the years you have talked a bit about how you may have paid a price career-wise for being yourself. You talked about the boys’ club earlier. Is there still the boys’ club dynamic in that what you did then is still something one might not do today?

I think everything is up for grabs now and changing, and this a great moment to be gay or transgender. Certainly when we think of what is happening compared to ten years ago, even if you are just thinking about RuPaul’s Drag Race being one of the most successful television shows and there is a transgender senator coming. There is at ton of stuff happening. I think the issue is still- it came up a couple of weeks ago when there was a Disney film and they cast the gay lead (character) with a straight guy, and obviously it was very frustrating to a lot of the gay actors in England who were of the same status or even higher than the person who got cast. But for me, beyond that what is very frustrating is that there is not this two-way traffic between straight actors playing the gay parts- in a way, I feel as soon as I commercialized the playing of a gay part all that happened was the straights came in and stole them. And there wasn’t any way of going any other direction.

Yet now we have Colin in your film and Timothée Chalamet last year. It’s almost a chic thing to do that.

Yeah but it’s not chic to go the other way. In that sense, the boys’ club and their prejudices about ‘a gay guy could just not make love to a woman’ kind of thing must be what’s at the bottom of it (we laugh at the unintentional reference). Really. Don’t joke! That kind of frat-ish attitude is what I would like to see changed. It is all very well with the gay guy getting to play the gay part, but why- and I think the same for transgender. I think the film with Scarlett Johansson…

Yes, she’s no longer doing it.

She’s no longer doing it. I find that’s a shame. Because what everyone has to realize is that it’s business. There is no transgender performer at the same level as Scarlett Johansson to facilitate the making of an $80 million dollar movie, and the Scarlett Johansson movie would probably be enormously positive toward the transgender movement and employ probably quite a few other transgender actors. I think that was a mistake. What I want to see is a transgender woman playing a woman.

Today I’m not sure Felicity Huffman would be playing the character she did in Transamerica. Remember that film?

It was great! I would never have missed, in a million years, Michael Douglas and Matt Damon in Behind the Candelabra. I was really moved by their connection to us and to how they worked and made it look so great. That film touched me a lot from just their personal commitments. So I don’t want to see that stop. At the same time, I agree it’s incredibly frustrating that Ben Whishaw or Andrew Scott or one of the other gay actors, who is more important than the one that got cast, didn’t get cast. But they should be playing big “fuck off” straight roles.

Thinking back to your time in Hollywood movies, what do you feel when you reflect on that era of My Best Friend’s Wedding and The Next Best Thing?

It was amazing. But the trouble with it was I couldn’t segue it into anything else. Every time I went up for a straight role I was put back by the studio; I couldn’t get it. So I had a choice of either going on as the gay best friend ad nauseum or doing nothing. And so I found it was frustrating that I wasn’t allowed to go into any other type of role.

What’s the best part about your job?

Oh, when it works it’s great. And it’s so liberating. You don’t work all the time. If you get regular work it’s wonderful. The downside is if your work dries up for a period of time and then everything starts backing up, like your bills and your mortgage. But I think it’s a wonderful job and one that is very difficult to relinquish.