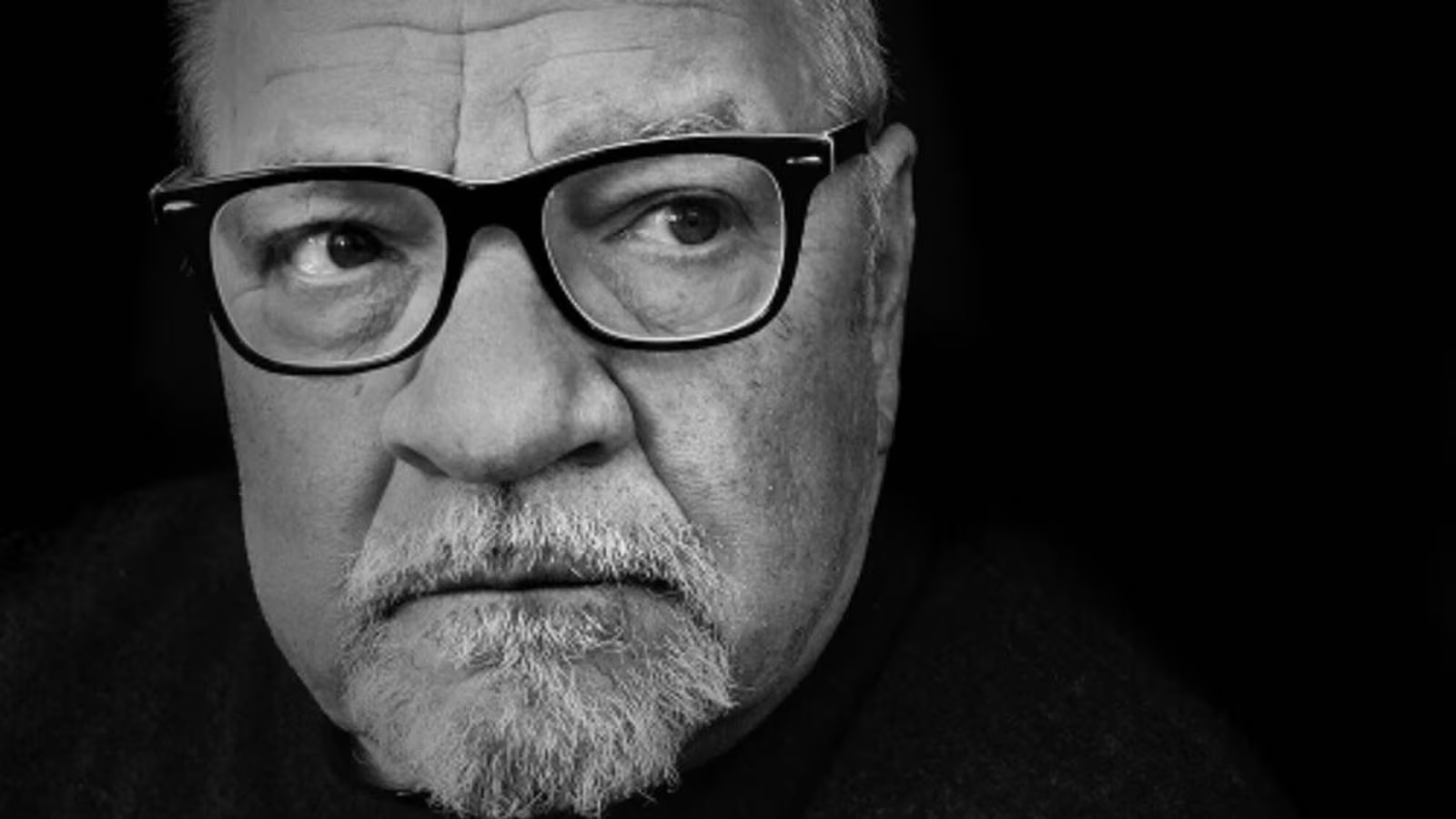

At 72, Paul Schrader has crafted one of his finest pictures in First Reformed, the story of a bereft reverend, played by Ethan Hawke, who undergoes a dark night of the soul before perhaps—or not—achieving transcendence. One of the few great pictures this year and as thematically bold and technically accomplished as anything Schrader has done, it observes a crisis of faith as sobering as it is unflinching.

Schrader, the early film critic and author turned filmmaker who wrote the screenplays for three Scorsese masterpieces—Taxi Driver, Raging Bull and The Last Temptation of Christ—is, as he puts it, an “analog” name in today’s market-driven, commercial movie landscape. The analog here is analogous with one of a master storyteller and richly probing writer whose early contributions to the form cemented his place in movie history.

His best pictures—Hardcore, Light Sleeper, Mishima, Patty Hearst, Auto Focus, American Gigolo and even The Comfort of Strangers—are often studies in obsession and descent with characters who reach for redemption, or maybe restoration, sometimes with spiritual deliverance.

In First Reformed, Schrader revisits and updates Taxi Driver in its tale of a man in isolation with a growing malaise about the world around him and a fractured sense of correctives, corrosive as they may be. Hawke, in a risky performance, follows Schrader to the depths of hopelessness, both in the search for forgiveness for the atrocities we’ve done to the Earth and our ability to embrace a church that has all but deserted its purpose in modern life.

Taking aim at big business, environmentalists, megachurches and even millennials, First Reformed bears the unmistakable mark of a complicated, still unsettled artist who, four decades after unleashing an iconic American movie character raging at perceived infestations of the modern world, instead seems resigned to accept that humans are now so far afield we may never get back.

I caught up with Schrader recently—and sitting down with such a maverick is quite a thrill—to chat about his new picture’s inspirations, from Bresson to Dryer, and his take on today’s industry versus the era in which his studio pictures entered the canon of the classics.

First Reformed is being called a culmination for you in some ways. It has very recognizable, what might be called Schrader-esque, themes running throughout it.

Yes. In March of ‘69 I saw Pickpocket, and it set loose two engines. One which was that style and the other was this idea that perhaps I could move from non-fiction to fiction. And so those two ideas came out of that screening. That was my Damascus Road. And now 50 years later, those two things meet again. And so it’s hard not to acknowledge the symmetry.

When you wrote Taxi Driver you’ve said that you were in a specific place psychologically. I felt many related currents running though this movie—isolation, a profound spiritual emptiness, the idea that one could become some sort of savior, or perhaps correct the ills of the world through radical means. Do you see them related?

There is a lot of Taxi Driver in this movie and much more than I thought. I did not realize until the editing room that there was so much in there. In this one, the anger is muted. This time someone is trying to choose to help and then chooses not to, quoting Romans, “There is no reason to hope.” But we can choose hope. And that is what he is trying to do, though not very successfully.

And Travis Bickle wasn’t trying to do that.

No, no.

Do you find First Reformed to be hopeful?

Well, that depends. Just because you choose to hope it does not mean that hope is warranted. And it just means that there is a level of delusion that makes life livable. For example, “I choose to believe that science will come up with a magic bullet to reverse climate change.” That does not mean science is going to come up with a magic bullet. It means that you are choosing that it is easier to live with this level of denial than without it.

Is the movie saying that we have destroyed the world and we largely don’t give a shit?

I think the speech he says- he’s made up his mind. The decision is in. And so, the Earth is not in fact in danger; the Earth is going to be just fine. You know, (there could be an) all-out nuclear war and 50,000 years from now the Earth is better off than ever. But the homo-sapiens are in a bad way. And whether there are several horses of the apocalypse, we pollute ourselves to death or use our technology to evolve into another species—those are the choices. Do you know the writing of Yuval Noah Harhari?

I’m not sure I am familiar.

He is an Israeli writer out of Oxford and wrote a book called Sapiens that was a bestseller. Sapiens is the history of intelligence from the beginning to the present. And then he wrote another book named Homo Deus, which is the future of intelligence. It is one of those books that gobsmacks you. I was just listening to an interview and he was saying long range thinking is not 2,000 years. It’s now about twenty years.

In a way, First Reformed gets into the psychology of an extremist, and one with whom we grow to identify. I always think if you have an actor you engage with playing whatever character, then you will go with him anywhere. I was surprised that by the end of the movie I felt as if I understood his necessity to do what he wanted to do, and almost empathized.

Well, one of the gimmicks of this kind of storytelling, which is true of Taxi Driver as well, is that you do not give the viewer any options. You are inside this guy’s mind and you are in his life. There is no other perspective. And if you do this for forty-five minutes or maybe an hour, people will identify and now you have them. And then the character starts to skew or go off the rails, little by little. But as a viewer you have already invested too much in him to let him go. So you find yourself identifying with someone whom you may feel is no worth of your identification. And then that kind of an exciting thing that can happen in art because it’s like your head cracking open. And not even the artist can predict what happens then—when you fuck with people that way.

You imagined different endings for the film and have said you feel it’s open to interpretation.

The first draft was the Bressonian ending and then after talking with Kent Jones, I switched it to the Ordet ending. I think that was the right choice. Because it just opens it up to interpretation and the possibility of miracles of grace.

My interpretation was that he drank the fluid as planned and experienced a vision of salvation.

Yes, that is certainly coded in there. You could also say, “Well, he dropped the fluid.”

Ethan Hawke’s performance in the final third of this movie is a real risk, particularly that moment where he observes Amanda Seyfried outside his window. It has the potential to be foolish, but he made something fascinating with the non-verbal things he does and even the sounds. Did he come up with this?

Yes, it’s like he’s an animal. Like a howl. He asked me about it. And I said, “It’s like any animal that has been speared. Imagine that animal howling and running around to get that spear out of its stomach.” So that was the image I put in his head.

You mentioned Muskegon, Michigan, in this film. I’m from a small town named Ravenna between Muskegon and Grand Rapids, where you were raised. I grew up in the area as well, watching your films in the 70s and 80s.

I know exactly where it is. I spent my childhood passing through it I bet. My people were from Muskegon, but we lived in Grand Rapids and went to Muskegon every weekend.

It’s not that great of a place anymore; when the industry goes, the town goes.

Yes, well Grand Rapids, thanks to Van Andel and DeVos, got into the hospital business.

Take me back to what the business was like for you in the late 70s or early 80s versus today. How is it now for you to make a movie?

Sure. Fortunately, I still have an analog name; one that was created in the analog era. To create a name in this era I would not know how to go about it. I lived in the sweet spot of history and the sweet spot of film history. After World War II we were in the most leisure time ever. We had everything. And then we selfishly destroyed it. And it’s very hard to- you have a fourteen-year-old son or somebody who says, like he says in the movie, “You knew all along. Why didn’t you do anything?”

Anyway, there was a magic spot in ’68 and ‘69 where a number of us walked into the room because they had left the door unlocked. Studios were starting to collapse. Paramount had sold itself to Twentieth Century Fox. They had these big turkeys. And they did not understand the youth audience at all. And there was a period of a few years where you could just say, “Today is your lucky day.” You just had to come into their offices and say, “The only thing I care about is making money. I am going to make some money and we are going to share it, okay?” And they would not know you were wrong because the did not know how to do it themselves. And a whole group of us came in that door. That door closed when Barry Diller brought in the market research concept from ABC and the studio executives were finally able to say, “We don’t need your ideas to tell us how to make money. We know what makes money and now we want you to do that.”

Recently I came across a treasure trove of letters. My brother died about ten years ago, and now my sister-in-law, a hoarder, is dying. I went through all their stuff and found this packet of letters I had written to my brother from ’67-’70. There was about one every two weeks and long letters. He was living in Japan and I was recounting everything—every movie I saw, going to UCLA, meeting Pauline Kael; everything. It was a time capsule of those years. I think Film Comment is going to print them, one a day, as an epistolic thing. But it is so fascinating to me to read them. It often feels like I’m staring into a buzz saw; just the ambition- the naked ambition.

Could you make a movie like Taxi Driver today?

Well, you don’t need to. That movie has already been made. I’ve been asked a number of times over the year to do a sequel. People are still trying to make it. I mean, that is the mistake—people trying to make a movie like Taxi Driver. It already exists.

Tell me a little bit about making Hardcore, can you? I’ve always been struck by the theme of a father nearly going to ends of the Earth to save a child.

Yes. Well, it’s a piece of juvenilia. It’s a young man’s film, thumbing his nose at his father, and it suffers from that. I also have a problem with the film because I was made to change the ending, and I can’t bear that ending. Columbia also forced me to cast an actor I thought was wrong. And those two things keep me from enjoying that film. Also, the fact that it just is such an immature film.

Some of the imagery in your films I think of often, like for example Susan Sarandon banging on the hotel room doors in Light Sleeper, George C. Scott covering his eyes and head in Hardcore, the blood washing over Nastassja Kinski’s shoes in Cat People and even The Comfort of Strangers, where Natasha Richardson is frozen, sitting there while the camera watches.

Oh, I like that film a lot. I think that is probably the best directing I’ve done in terms of camera movement, mise-en-scène. It is quite rapturous that way.

What’s the best part about what you do?

I had this conversation with Scorsese awhile back, about when you get a buzz. When you begin your career, if something goes wrong it induces a lot of anxiety—the weather is wrong, the actor is no good or something just isn’t working. And you tend to sort of panic and you realize that all your best laid plans are not going to work. But then if you do it enough, you get a quiet peacefulness and you can say to everybody, “Just give me fifteen minutes.” And you sit there knowing a solution is going to come, because it has come before in the past. And then everybody comes back, and you say, “Okay, we are going to do this entirely differently now.” And that sense of confidence you get—when you know the idea will come—is really gratifying. I talked to Marty about that and he knew exactly what I was talking about.