What is the price of sleepwalking through your own life, as years pass, friends move on, other people grow up and plant roots—and you don’t? Filmmaker Mia Hansen-Løve’s Eden is at once an exhilarating illumination of youth culture and a serious examination of a life half—or less than half—lived, a portrait of the artist as a young man who eventually becomes neither.

Co-written with brother Sven Hansen-Løve, an internationally known DJ and architect of the French underground garage music phenomenon circa 90s, Eden is semi-autobiographical look at his rise and near freefall across over two decades before reinventing himself by returning to his true passion—writing.

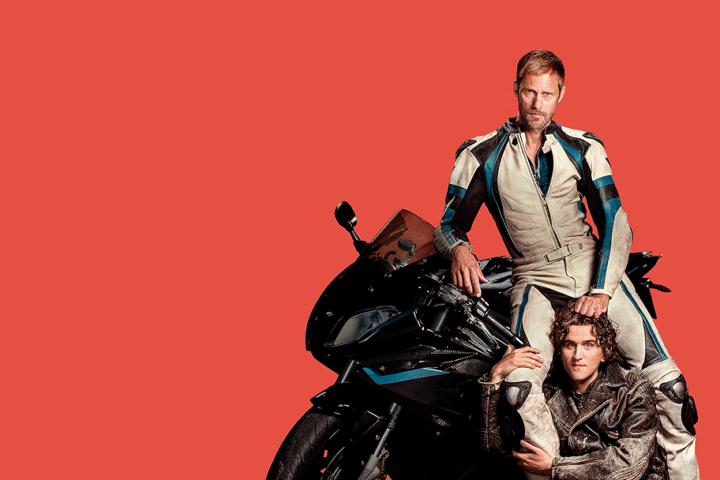

Deftly charting the changes in the French music and club scene from vinyl to digital and across evolving genres, Eden becomes something moving courtesy of fledgling French actor Félix de Givry, investing the picture’s second half with a sad melancholy.

I recently caught up with Sven Hansen-Løve and Félix de Givry at Chicago’s tony James Hotel to chat about Eden’s unique road to the screen, individual cultural milestones and the film’s unique approach to depicting both its world and anti-hero.

You must go through a number of emotions seeing your life in this movie.

Sven Hansen-Løve: Yes. But it’s not like I went in the theater and discovered my life. I was so intensely involved at all stages of the project—writing, shooting, editing—that I never had any kind of distance. Only when it was released in France did it become a bit strange, because people came to talk to me like they knew me. But it was a natural thing and never was problematic or embarrassing.

How much of what we see onscreen is what you actually lived through?

SHL: It would be hard for me to be sure because I wrote it with my sister three years ago, and she interviewed me for hours and took endless notes, then she started the drafts and I worked with the scenes. Some of it I do not remember, and some of it blends together. About half of it is real life.

There are forty-five songs in the film. Did you write the scenes with those songs in mind?

SHL: No, only maybe two or three. Mia had some of them in her mind, but she knew it could change. But she really wanted the rights to the songs before the shoot.

It sounds expensive.

SHL: Not so much, because Daft Punk really helped us. They gave us theirs for a really cheap price, and we made a special contract for all songs that they all pay the same, not more nor less than Daft Punk, otherwise it would have been crazy expensive. Luckily, there were many artists and they were happy to be involved.

Take me back to the moment that you decided you wanted to be a DJ.

SHL: I guess I was already doing it for a few years and earning some money. But you know what? There was never one point where I said I was going to do it for a living. Never. I just did it. And I was always postponing writing, and I had some gigs and was earning money and had no time to write. I never thought I would be a DJ the rest of my life.

Was there a particular musical moment that set you on this track?

SHL: Several. The first time I came to New York and went to the clubs. That was very important. I remember when I was 20 and I went there for a month, by myself, to learn English. When you are young and you go by yourself it can be an intense experience going to a club and the intensity of the music, the people in the club and the DJ. I fell in love.

Félix, did you have a similar moment? You grew up in the 90s.

Félix de Givry: I was born in the early 90s so I was very young. I am still young. But there was this first wave of French Touch with Daft Punk, and a second wave with a band named Justice and a label called Headbanger. I was more into that wave and era, which was maybe 2007-1008 when I was about 18. Electronic music was already everywhere, so it was a matter of which electric dance music you were going to listen to, versus rock or pop.

Share a bit about your upbringing and youth.

FDG: I grew up in the south of France and in Paris, and when I finished high school I did university in France and an exchange program at UCLA studying cinema and literature. And very shortly after I completed high school, I started to organize some parties with friends, which were successful, which led to creating a music label. We released a few artists and one was a huge hit in France. With that money we started to do other projects, including producing some films. Then I did Eden on the side. I want to be involved in cinema, writing and music.

Interesting that you said “on the side” about your starring work in Eden.

FDG: It is my first big film. I had a very small part in Olivier Assays’ Something in the Air, but this is my first big role. It’s very important in my life, and I have received some propositions since Eden, but I want to be involved in some that are either masterpieces or where I am more than just an actor, and have a personal relationship to them.

Sven, the film clearly shows the difficult family dynamic and the toll it takes on Paul’s relationship with his mother, played by Arsinée Khanjian. Is that autobiographical? Were they supportive?

SHL: It’s kind of autobiographical. My family supported me. My parents were teachers and liberal. They developed an approach to education that said if I wanted to do it, then I should do it! So they helped me—sometimes I think too much! They were really supportive, also financially.

One of the film’s great strengths is its authenticity in the club scenes. Often in movies, “scenes” can feel very contrived and not genuine. You must have worked very hard to get it right. What were the keys?

SHL: Absolutely. The way the music is being played in the club—and how it sounds—are most realistic, but also thinking about other aspects. As you said, there are many club scenes in movies, but we wanted to make sure ours didn’t look the same. The sound design was really important. We watched a lot to know what we wanted or didn’t want to do. We had a good example of 24-hour Party People, and it was realistic as well, though different than ours. And Mia thought to be authentic would be more powerful than to romanticize it or glamorize it. We wanted to stick to the truth.

Yes, that’s it—normally in movies there is an overt sexiness to it.

SHL: Of course, there is this natural thing that people believe, that clubs are all extremely sexy and glamorous. In truth, there is a mix of good and bad, and that was the feeling that we wanted to capture.

FDG: The extras were very important. They were real Parisian club people. They are really dancing, rather than just actors who didn’t make it and are now trying to show off on camera. Most of the club scenes felt like parties and they were really having fun.

Félix, it must have been challenging in your first big role to play twenty years in someone’s life, and to shoot it out of sequence.

FDG: Mia wanted to shoot everything in order but it was impossible. So yes, we ended up with scenes that were from three different sequences, from ages 22 to 34 to 37, being shot in the same apartment. It was kind of messy, but for me this was also the story of the character; someone who is not evolving. When I read it, one of the things that really struck me was that it starts by him saying, “Listen to the silence.” And then at the very end of the film, the character has a sort of nervous breakdown and cries, asking again for silence. His life has been very noisy for a long time, and only when he finally finds silence and solitude near the end is there a difference. The rest of the film is about him not really knowing where he is going.

And time is passing.

FDG: And time is passing. And that was the feeling Sven told me about—you wake up one day and you realize that ten years have passed.

SHL: It’s kind of what happened to me. I was so into the music and had this drug addiction, and the people around me were making changes and progress in their lives, but I didn’t realize this because I was partying all the time. One day I woke up and realized time had passed and I hadn’t seen it. I was like, “What happened to me?”

There is a heartbreaking line late in the movie where Paul says, “I used to work in music.” It really got me. For me, it was about the death of the dream of an artist. Is that a fair interpretation?

SHL: Yeah, yeah it’s true. I said that many times because it is the truth. But a film is just two hours, and then suddenly at the end he says that, but for me it is a lifetime so it is different. Seeing a life of twenty years in two hours makes that even more effective. Things go so fast in life.

FDG: Some say the movie is about a guy who didn’t make it, but for me he makes it because he confronts himself and makes it back to what he wanted to become—a writer. He was not a DJ. That was a fake path, and the wrong way.

Félix, I was very affected by your performance in the film’s last half hour. There’s a scene in a park, and another where you confess to your mother that you are at rock bottom and have nothing. Can you talk about those moments?

FDG: I think that was one of the things that was most challenging when I read the script was because it was a character who was not able to hold onto something. At the end, it all sort of builds up. So it was challenging. The scene with mom in the apartment was the easiest in a way because it is a sort of sadness that I feel is kind of close to me somehow. I’m not sad at all in life and am different from this character, but to produce that feeling for a character who was wandering around… I understood it. That is also why the second half is great. It’s my favorite part. It’s really getting into real acting, you know? Like going through emotions.

The movie is almost anthropological in how closely it examines youth culture, something that changes so quickly. How do you think it has changed today versus at the time of Eden?

There are many things to say on this, but one of them is the incredible progress of technology that continues to change so quickly. I started with vinyl, which became CDs. But then the CDs became the laptops. People are coming to DJ with laptops.

That is a bittersweet moment late in the film.

Yes. And even that is already over! Now it’s the USB. So we started with huge boxes of vinyl and now we just come with small USB, and a computer can even mix for you, so the technique is not as important. Now what’s important is the feeling and the selection. Also, electronic music went so big and mainstream, so while the underground scene still exists, today there are so many different types of music and so many places and clubs and people listening. When we discovered it in the early 90s, it was more underground and really special. We had a feeling nobody had known. It’s already now a music of the past.

Do you still have your vinyl collection?

No. I had a lot of vinyl but I had no more space in my flat, so I gave them to a friend with a huge store and an underground basement, so I can go there when I want and listen to them, which is perfect. I don’t use them anymore. I’m lazy.