We know how he did it—on January 26, 1996, billionaire eccentric John Eleuthere du Pont shot and killed, in cold blood, Olympic wrestler and gold medalist Dave Schultz. But why did he? Foxcatcher, Bennett Miller’s arresting new picture on the subject, has some very potent ideas why, and features three indelible performances in a film of austerity and precision, an examination of class, exploitation and obsession.

In a revelatory dramatic performance, Channing Tatum is down-on-his-luck former Olympic gold meal wrestler Mike Schultz, whose dreary life consists of training solo when not holed up in a claustrophobic apartment, or sparring with his more garrulous and better-liked brother Dave (Mark Ruffalo), also a gold medalist and while smaller in stature, in whose shadow Mark resides. Even an opportunity to address an elementary school class is but a fill-in for his otherwise engaged sibling, and Tatum, with jutted jaw and downcast eyes, vividly renders a lonely, hulking giant.

This changes when Mark receives a mysterious call from one John du Pont (Steve Carell), who summons him via private helicopter to the family compound, a sprawling, 800-acre estate near Valley Forge, immediately seizing on Mark’s insecurities by sweeping him up into the rarified privileges of both the wealth and du Pont’s own close friendship, which the picture suggests strongly is something more for du Pont, a possibly repressed homosexual identity submerged by self-loathing and insecurity.

Mark’s social and economic deficiencies are preyed upon by du Pont, himself a late-life wrestling aficionado with a dream to build and train the next U.S. Olympic wrestling team at the family estate, which he nicknames Foxcatcher Farm. Never mind that du Pont is off-putting, pushy and clearly has something up his sleeve—he has the means and vision, and after moving Mark into a property guest house, is quickly informed that brother Dave “isn’t for sale,” an idea foreign to du Pont.

Perhaps the film’s most important relationship is between du Pont and the family matriarch, played in two highly concentrated scenes by the great Vanessa Redgrave, who casts a disapproving judgment on a son she considers a failure, one who indulges in petty hobbies like toy trains and trophy cases, and their pointed discussion about her distaste for his wrestling endeavor is followed by wordless scene where she sternly observes the team training.

It isn’t long before Dave and family (including Sienna Miller, as wife Nancy) join Mark at Foxcatcher, and the older brother quickly surmises something strange afoot between Mark and his benefactor, raising the stakes between all three and eventually culminating in tragedy.

There’s a rather heavy metaphor that figures into the film’s climax, and as the matriarch collects and breeds fine horses, so does her disturbed son breed animal machismo in his team. When hell breaks lose in the final act and those horses are freed—well, you know what’s coming.

Beyond the facts of the well-publicized case, what Foxcatcher is really about is the sense of entitlement that great wealth breeds, the idea that people of modest means are but playthings for the rich, to recruit, seduce, discard or even murder at will. The minimal, absorbing screenplay by E. Max Frye and Dan Futterman essays a number of fascinating themes, including a very timely commentary on the gulf between the very rich and the lower middle class, here presented as an issue of exploitation and abuse of trust and loyalty, an examination of how madness and insanity is allowed to fester, rot and run amok when ensconced in great wealth, unchecked neuroses disregarded as simple eccentricities or merely the diversions of an oddball philanthropist, when in fact they were something much darker.

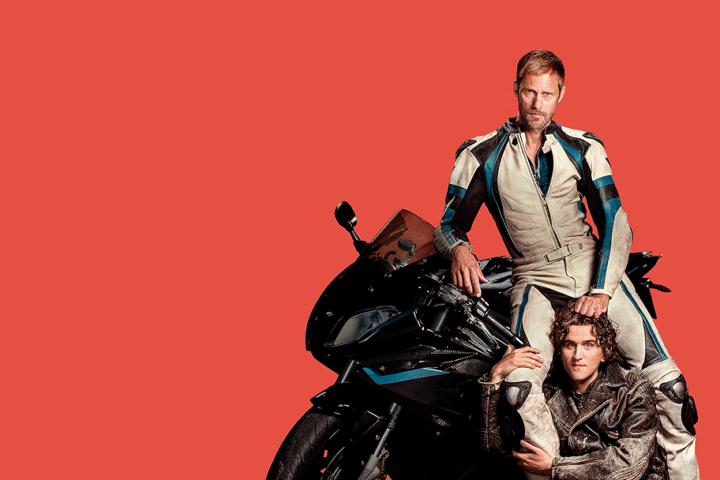

Much has been made about Carrell’s dramatic transformation, but at least equal credit for the power of this picture should be granted to a revelatory Tatum, an actor who has flirted with untapped dramatic reserves if seldom finding the vehicle to express them.

In a very competitive Best Actor Oscar line-up this year, it seems nearly impossible that Carrel won’t make the cut. Like Rosamund Pike’s fictitious phantom in Gone Girl, it would be easy to write off Foxcatcher’s John du Pont as a simmering psychopath, but Carrel labors intensively to give us a complex portrait of a man coming unhinged, layered with issues of control and paranoia.

While some may find Miller’s style here to be remote or perhaps even bleak, the performances and thematic richness deliver the picture.

3 1/2 stars.