Geoffrey Rush and Sophie Nélisse play a small-town, working-class German father and adopted daughter on the eve of World War II in The Book Thief, based on the popular best-selling novel by Markus Zusak and featuring lovely performances from the pair, and Emily Watson as their stern matriarch, a noble if simple family harboring a Jewish refugee while fascism comes to their little village. It’s an ambitious picture that uses a large canvas backdrop to tell the story of an illiterate child who learns to read, and understand the power of words while the darkness of Hitler’s regime closes in.

I recently caught up with Rush, Nélisse and director Brian Percival to discuss their German-based shoot, the tender onscreen relationship between Rush and Nélisse and the lingering traumas of recent heritage in modern Germany.

The Book Thief has epic dimensions, but is personal as well. The father-daughter relationship is quite special.

Geoffrey Rush: I’m pleased that you see the film as being an epic, because the thing that I like most about it is that yes, it is about a very well-documented period of 20th century, German World War II history, but that it is seen through the eyes of this grief-stricken young girl. In the book and the film, her brother dies on page one. And that is where the protagonist starts—right off the deep end. But the fact that it is in a small, average German town felt very fresh to me. You get to meet people in the street, as she does. She gets to meet her new foster parents. She gets to meet Rudy next door. She meets his parents. She meets the people who live down the road. It’s a communal quality and I think that something emerges. Maybe it’s an instinctive, emotional intelligence to Hans. He’s a simple guy, but he has that quality because he likes music and doesn’t want to join the Nazi party. He reads her barometer quite clearly at the beginning to understand he has to tread carefully because she is in a horrible position for a ten-year-old. He uses music to communicate and happens to pick up a lullaby that she is singing. That tells her it’s okay to think about her brother in that way without saying, ‘Do you miss your brother?’ You know what I mean? We let that unfold organically because we shot all of the kitchen stuff on a studio set in the first month. We covered all of that early, and it was a good way to do it, to discover how Rosa and Hans are within their domestic environment, and what it means to them that they have a new child. And then of course, we didn’t do the bedroom scenes until the very end of the shoot, and they were the heavy scenes of having to explain to an eleven-year-old the deathly implications of the political secrecy.

Certainly the story has a lot to do with the power of words being used for good or evil.

Certainly the story has a lot to do with the power of words being used for good or evil.

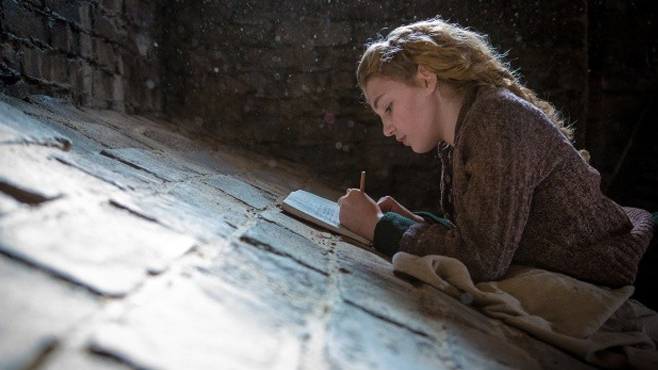

Brian Percival: The way to translate that literally was to see the impact those words have on Liesel and how she took control of the words. I think we see her voyage of discovery, first putting words together under Hans’ guidance and then, when finishing her first book, she understands what language is and how to use it. But then Max comes along and opens her eyes and gives her a way to see the world. We had to illustrate that in sequences where we put the words on the wall in the basement and as part of the books she was reading. But it really had to be about the impact on her character.

GR: It’s a great visual image though, isn’t it, to actually be able to see in the film as opposed to the book, or to hear the accordion. Seeing Mein Kampf actually painted over and then writing her story afresh, is pretty good stuff.

One of my favorite themes in literature and film is the loss of innocence, that point in life where you start to look at the world differently if you’re a child or a teenager. Sophie, I’d like to hear your thoughts on that, and maybe about your own life. You are still so young.

Sophie Nélisse: Well, because I did a big movie it might change the direction of my life, but I don’t feel any more grown up. I want to stay grounded and not become a superstar or princess. I’d like to stay a little girl as long as possible. I find it interesting how my character changed her life by reading books. Sometimes when I have to read a boring schoolbook, I try to look at it in a different way, like my character did. If will try to find all of these little things and understand it. But the end of the book I look at it in a different way, and how it changes my perception. So I think that is it.

Sophie, I have a nephew close to your age and I wonder if your generation is a bit different in terms of how you read. Do you read mostly on your phone, or do you also pick up a novel?

I think we spend too much time on electronic devices. I think we have to keep books- you can discover so much about history. Also, books make you see the world in a different way. It’s an important part of life! It can make you completely change the way you think, or even escape reality for a short period. I think books are part of life. And that this (gestures to iPhone) is just something made to make money, but books are something really basic.

Geoffrey, you have played your share of larger-than-life characters. By comparison, Hans is deceptively normal.

Geoffrey, you have played your share of larger-than-life characters. By comparison, Hans is deceptively normal.

GR: That was of great appeal when this screenplay came my way. The last two or three years, I’ve been doing a lot of theater and some film, so I’ve gone from The King’s Speech to playing Lady Bracknell in The Importance of Being Earnest. Earlier this year I did Pseudolus in A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum. You can’t get much more burlesque or bigger than that. So the timing of this was really, really nice because I thought it would be great for me almost as a discipline and change of mood to play something that had almost bland adjectives to describe the character. He is an average guy in a small town with nice emotional intelligence, but he is a housepainter, a working class guy with a love of music but in a very amateur kind of way. So the simplicity of it was really important. As the story goes on, realizing that all of these characters, through the story and screenplay, they just start getting deeper and richer and secrets come out of all of them. Even Rosa, who is such a sourpuss through much of the film, is bursting with love for this girl, she just expresses it in a different kind of way. And then discovering that Hans is sort of a political maverick by default. He was sent away and was a part of the about ten percent of the German population that felt Der Führer was taking the country down the wrong path. Ninety percent went along with it. There were fear tactics. It was terror and anxiety, and it was probably better to keep your head low.

Yet there is that scene on the street where you are the only one who stands up in defense of the persecuted Jewish shopkeeper.

BP: There are others who want to be involved, but are afraid they will put their families in danger. It’s scary how people just believed and went along, thinking, ‘This is a great path to follow. What is wrong with this?’ The idea is that we should not just look at a bunch of people from that time as all the same. They were individuals with normal lives, ordinary people, and then suddenly something happens.

What Geoffrey said about Hans being depicted as a normal person is one of the values of this movie, even through a modern context. It’s much easier to drop bombs if we believe, for example, that everyone in a given country is our enemy. Then we see a film like A Separation, about a middle class family very much the same as ours, and we know that is not the case. You also shot on location in Germany. Did the German citizens have trepidation about the story being told again? The iconography is bold.

BP: No. 95% of the crew and the vast majority of the actors were from Berlin. Everyone around us was German. I remember the uber alles sequence with the book burning. We had about 450 extras, and we had to teach them the words because it has been banned since 1946. So during the afternoon they were given lessons because they had never sung those verses before. The actual verses are incredibly creepy when you see the translation. A number of crewmembers had tears rolling down their cheeks. It was shame about what the country must have been like, and what they have in some way been paying for since they were born. They still feel the shame from what their forefathers supported. It was incredibly emotional and helped me as a director to have such an influence on the crew and cast.

GR: You mentally take a serious step back when you are with Germans of all generations. We were in the green room together, and seeing the swastika and books had a dimension that was above and beyond. I was a teen when John Lennon had made the misinterpreted quote about being more popular than the Beatles, meaning more people know about them than know about Christ. It was probably a pro-religious statement in a funny kind of way. The reaction was that ‘We are going to burn all of your stuff and wipe out your belief in that.’ It’s a destructive part of the human psyche that is frightening. When I first read the novel, you get the flavor of the town. But it’s very easy metaphorically to see that this is where a fanatical ideology took over. I remember first being on the set and in the cake shop was a photo of Hitler. It was so sly and easy and the swastika brand and red strips were a powerful logo. No words. It has a mental authority that is curious. We tried to be very culturally authentic and were surrounded by some extraordinary actors from German cinema and theater. It was invaluable to have shot in Berlin. I’m sure that producers could have said it would be cheaper in Romania or Budapest.

GR: You mentally take a serious step back when you are with Germans of all generations. We were in the green room together, and seeing the swastika and books had a dimension that was above and beyond. I was a teen when John Lennon had made the misinterpreted quote about being more popular than the Beatles, meaning more people know about them than know about Christ. It was probably a pro-religious statement in a funny kind of way. The reaction was that ‘We are going to burn all of your stuff and wipe out your belief in that.’ It’s a destructive part of the human psyche that is frightening. When I first read the novel, you get the flavor of the town. But it’s very easy metaphorically to see that this is where a fanatical ideology took over. I remember first being on the set and in the cake shop was a photo of Hitler. It was so sly and easy and the swastika brand and red strips were a powerful logo. No words. It has a mental authority that is curious. We tried to be very culturally authentic and were surrounded by some extraordinary actors from German cinema and theater. It was invaluable to have shot in Berlin. I’m sure that producers could have said it would be cheaper in Romania or Budapest.

BP: What it did was give us an authenticity because the history is tangible and you are reminded of the Third Reich and what happened after that, when most of the Nazis’ became the Stasi, the secret police of a new regime. So you are reminded of that always. You are mixing with people whose fathers and forefathers were involved in those.

Sophie, in the film Liesel develops a strong friendship with Max. What is your best friend like?

SN: Well, my best friend is a gymnast I used to train with. I like her so much and I like my friends so much because they do not treat me in a different way just because I am an actress. Some of my friends I have known since I was in third grade. It’s been five years that I have known them. It’s not because I do an American movie that I am different. Obviously, when I walk into school people look at me, but my friends just accept me and don’t do anything special because of the movies. My friend is not into popularity when she is watching the movie. She will be like, ‘Who is that? Is that a boy or girl?’ And she will be speaking in the theater! I’m like, ‘You can’t say that.’ These are always going to be my friends. I don’t want you to be my friend because I am famous, but just who I am.

You also have a lot of vulnerability onscreen and are able to freely let your emotions come out. It might be hard to articulate, but how does that happen for you?

It’s special, because most actors I think feel emotions onscreen. But I don’t at all. In anything I do, I don’t feel anything. I never have any feeling. When I have to cry, I think of something sad. But when I am actually doing the scenes, I can be thinking of the most ridiculous things—like what I ate yesterday, or what I have to do tonight for school.