The principal reason to see The Impossible is the herculean performance of Naomi Watts as a real-life wife and mother swept away in the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami, fighting to hang onto her life and family. In a film directed by the gifted Spanish director Juan Antonio Bayona (The Orphanage), Watts’ powerfully rendered stamina and depth of conviction trump a well-meaning but marginal movie, albeit one that stages a staggering opening sequence—the tidal wave and the havoc it wreaks—and then undoes that power somewhat with a dozen or so emotional climaxes that, for a gritty true story, give it a Spielbergian Hollywood gloss, the kind designed to wring tears more than insights.

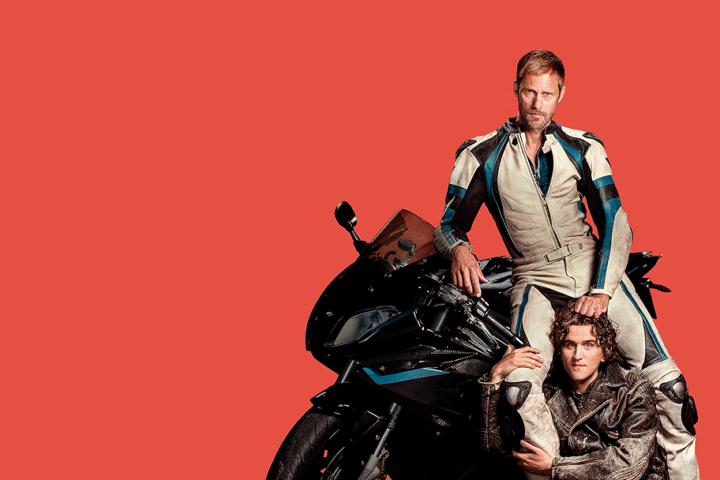

We first meet Maria (Watts) and husband Henry (Ewan McGregor, superb) on a plane speeding toward Thailand, three sons in tow. The younger boys (Oaklee Pendergast, Samuel Joslin) are typically rambunctious, while the eldest, adolescent Lucas (Tom Holland) is reserved, sitting separately from mom and dad. It’s a typical and convincing family—a British one, by the way—based on the very real story of a Spanish family who served as consultants on this picture.

Carefree on Christmas vacation, they have no idea what is about to hit them, and the deceptively serene opening scenes are excruciating to watch. We know what they are in for, or at least we think we do, until Bayona gives us a ten-minute coup de grace sequence of force and fury.

Nothing we’ve seen in disaster movies, including Clint Eastwood’s admirable Hereafter tsunami sequence, prepares us for the shock wave that slams into the family’s beachside resort (a perfectly reconstructed version of the actual hotel that was destroyed) taking down trees, building, cars and families, hurling Maria through a glass window and into an abyss so terrifying as unable to be described, rendered here largely without excess CGI (though some tasteful touches) in a multi-million gallon tank where actors Watts and Holland were bobbed and hurled on pulleys, swept up and down and literally beaten to a pulp.

When Maria comes up for air, amidst dead bodies and debris and in the current of a raging river, clinging to a tree, she immediately hears Lucas’ cries. What follows can only be described as primal drama, the pair connecting and parting in the rushing melee like spinning tops—undoubtedly one of 2012’s most powerful movie sequences, and something we have never seen in such nightmarish detail.

When the water recedes the landscape is destroyed, death is all around, and not far from severely wounded Maria, a doctor herself who knows that without medical care, she will not survive her injuries. Lucas, shocked at seeing his mother in such a vulnerable state, takes a commanding role in helping her get to an overtaxed hospital.

Miraculously, Henry and the younger sons have also survived, feverishly searching the destruction for Maria and Lucas, each party believing the other to have perished. The rest of the picture tracks the loss of innocence Lucas experiences as he becomes a integral part of reuniting families and victims in the chaotic hospital housing his mother, and young actor Holland performs with impressive sensitivity.

But somewhat hampering the built-in survival story, itself sufficiently gripping, Bayona works our tear-ducts overtime with a bombastic score underlining every reunion, ample waterworks from everyone onscreen and tonal melodrama that threatens to overturn the grittiness. And there’s some blatant manipulations in the film’s climax as the family members nearly run into each other—several times—in the crowded hospital corridors, leading to a reunion between three characters that goes unabashedly over the top.

Curiously, Sergio G. Sanchez’s screenplay focus solely on the plight of visiting Caucasians; not a local is featured in a role other than health care professional or caring villager, and this feels like a myopic oversight in a situation-driven screenplay too light on characterization and too reliant on situation.

Since the disaster occurs in the film’s opening scenes, we learn little prior about these people other than cursory information about their careers and family dynamic. Consequently, we are left to bring our own sense of empathy to the situation, which has this has nothing to do with well-written characters and everything to do with the compassion we feel for human suffering. The Impossible is a bring-your-own-empathy proposition; the characters only exist insomuch as the situation dictates. We’re not given dimensional people before the wave hits, and the actors work hard to compensate; perhaps that’s the point—they are tested and redefined by the tragedy.

Yet just as she rises from the abyss in the film’s opening sequence, magnificent Watts rises far above these limitations, surely headed for an Oscar nod, so fully felt and emotionally precise as a mother trying to survive for her children, that we can’t help but be moved by her heart in the film’s spectacular final shot, which speaks volumes.

3 stars.