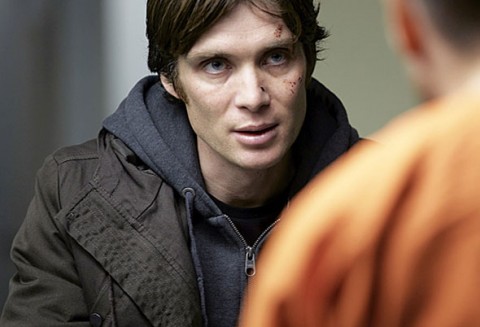

In filmmaker Rodrigo Cortes’ Red Lights, Sigourney Weaver and Cillian Murphy are skeptical scientists whose mission is to disprove paranormal phenomena, which leads them down a dark path once they set their sights on Robert De Niro, playing a renowned master of ESP who just might be legit. It’s a movie that balances the opposing notions of scientific explanation and the possibility of unexplained phenomena, nudging us back and forth throughout its running time, right up to a surprise reveal in the climax.

Densely plotted as it is, Red Lights is most notable for the conviction of its heavy-weight actors, who bring gravitas to a story that keeps us guessing. Weaver and De Niro are the old-school pros matched scene-for-scene by Cillian Murphy, as Weaver’s protégé, who undergoes increasingly intense paranoia in the film’s final reels, which undermine his character’s peace of mind en route to some hidden truths.

I caught up with Rodrigo Cortes and Cillian Murphy recently to chat about Red Lights, its shifting metaphysical ambiguities and strong performances from the heavyweight cast.

The most interesting thing about many of the events in this film is that they can be perceived as real or paranormal depending upon your vantage point.

Rodrigo Cortes: Yes. In this film, everything is about duality and ambivalence. I wanted it to be very physical, touchable and tangible. It deals with the paranormal, but in a very scientific way. As an example, imagine that Cillian now gets very angry and everything in this room starts to tremble. That is physical. It may be him projecting his psychic energy or it may be the underground; an earthquake. So there is always another possibility. In the film, the audience changes its opinion several times, so in the beginning you learn clearly that this kind of paranormal phenomena cannot exist. But then something happens, and you have to reevaluate the situation several times. The other thing is always possible. And then when you are sure that everything is a set-up, there is still the supernatural option which can be possible. And when you are sure that strange things are happening, you can still find a physical explanation for that. It’s like stories that work on different levels, especially when it’s not too on-the-nose, stories like those of Richard Matheson—very simple premises, but they manage to talk about human nature. But not in a pretentious way. It’s something that you find out inside you. You begin to think on many different levels, even though the story is about a guy who has a conflict with his wife, then a mouse or a spider, maybe.

Cillian, working with De Niro and Sigourney Weaver, who is brilliant here, must have been edifying.

Cillian Murphy: I think that he and Sigourney know their reputations and legacies and must know what effect that has on other actors. So they were sweet, warm and generous to me during the shoot. I was in awe of them, but never intimidated. Rodrigo was great. I remember my first time meeting (De Niro), and Rodrigo was like, ‘Well, this is Bob, you may have seen some of his films, now let’s go.’ So we just got down to the work and it became instantly about that, which is what we were there for. The man traveled to Spain to make this movie. He wasn’t getting paid; he just wanted to be there. It was about the work.

You must get a lot of interesting reactions to the character of Tom Buckley, and where he ends up at the end of the film.

CM: I have had people ask if he is an angel, and that is a fair point. But the beauty of the subjective interpretations is what you want. For me, I want to go to a movie and come out and start arguing, and have a very clear point of view about it, instead of being gone in a flash, as some films are.

RC: As an audience member, I don’t expect films to please me, but rather to challenge me. I want to hear a clear voice and point of view. As a director, I try not to be prescriptive. You have to keep thinking after the film ends. It goes on inside your head, which is what I really want to. But still, (as a director) you put certain things there. It is a story of self-acceptance and obsession, and you want to deeply affect people. People are having very strong reactions to certain things. Sometimes they are rational, sometimes not, but they want to think of the film in certain layers and when that happens, you feel very happy. You try to be challenging in that sense.

Can you share some insights into the climactic scene between yourself and Robert De Niro?

CM: That scene was amazing and something I will never forget. To get to go toe-to-toe with Robert De Niro was unbelievable. Aside from the fact that he is a living legend and one of greatest actors ever, when Rodrigo said, ‘action,’ it just became about two actors trying to help each other. There is a lot of dialogue and cues, so he would tell me what he needed and I would tell him what I needed. In that way, it wasn’t any different from any other material or performance.

RC: It’s one of my favorite scenes in the film. In a regular Hollywood film, there would been rays of energy and an amazing final duel, but we tried to capture that energy in their performances and in their intensity. And it was so moving to me to see that duel. They trusted and helped each other, and it was about dissolving in the character. It was heartbreaking. It works in terms of performance and it was heartbreaking for the crew to see him so destroyed.

Let’s discuss the tone of the film, which harkens back to the great conspiracy thrillers of the 70s.

The tone of the film is that we wanted it to have the general code of a political thriller of the 70s, in a way—Costa Gavras, Alan Pakula, The Parallax View. When you see these films, they trust characters and actors and performances, and take that seriously, and with this very physical sense of atmosphere. Imagine All the President’s Men, which is so real. That is what I tried to get. So if you felt it, I am so happy.

Yet as dark as the film becomes, there is still a ray of hope for Tom.

CM: It’s definitely there, isn’t it? Human beings are always desperate for hope, aren’t we? I think this plays into Tom’s story of self-acceptance and obsession, things we all can identify with, and equally that story of hope. You hope that Tom is going to be okay and that whatever journey he goes on next, everyone will be okay. I’m glad that you saw that.

Rodrigo, you have the science here in Red Lights. But you’ve got three great actors here creating interesting characters.

RC: It has a lot to do with the 70s, this golden age when films like The Exorcist or Rosemary’s Baby were challenging, or even The Entity, which was later, but has a very scientific process and a great performance. So you get real characters from them. Nowadays, you have seventeen-year-old kids killing each other in them, but when you think of the performances of The Exorcist, that is something that they really respected.

Without giving anything away, the ending threw me a bit—didn’t see the twist coming.

RC: To me it was important to make it about self-acceptance and not to find a final twist. So if I wrote it again, I don’t know if I would do that twist, because people expect to see The Sixth Sense. When you have a final twist, that is all people care about and the rest is not important. So I didn’t start with the twist. I started with the research for a year and a half, trying to understand both sides of this world—the skeptics and the believers. I found out something very interesting, which is that no matter which behavior it is, they just confirm to their previous positions and reject everything that put that at risk. We believe what is more convenient for us. Then I started to create characters with complex psychologies and contradictions. Then you start to tell what you want to tell. And then I decided how I wanted it to end. When you finish your first movie, you know what you are trying to do with your film. So in the rewriting, you put every element in a certain direction, but it happens in an organic way. I never work with a treatment. I hate treatments. They are so restrictive. Before creating you have to have a very clear idea. I am always open to a more organic process.

Did Buried make Red Lights an easier picture to produce and direct?

RC: It was easier, but on the other hand a bit of a problem. When you do a movie that happens inside of a box, or something like Memento where you do a movie backwards, they are going to tell you to do another movie backwards, and if you do it the conventional way they will say, ‘I prefer the other way, because it was backwards.’ So you cannot think of the that pressure, only of the story you want to tell. (On Red Lights) things were not easier, but they were faster. We got amazing responses from the actors.

Cillian, I know you are a skeptic about the paranormal. Anything change your mind during the making of the film?

CM: I’m so annoyingly rational. In real life, I am so involved in this dimension! The research was fascinating because it was endless. Where is the reliable source? Do you know what I mean? In that case, I would always go with the science, which is about investigation and results. I did Sunshine a few years ago and similarly there I was sort of on the same side. I guess I can’t.

RG: I’ve really enjoyed this conversation.

Thank you very much.